Accessible Fluid Typo

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home quite on currently the market easily

The Sans Selection

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home quite on currently the market easily

The Red Room

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home quite on currently the market easily

Most Recent

The Game That Finally Lets You Live Your Fantasy of Being a Bickering Married Couple

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and singer Jennifer Lopez from expanding her property collection. Lopez has

Sports

Top of the week news

Zion Williamson Is Basically on the Knicks Now

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and

What Happened to Christian Pulisic?

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and

What Is the Most Exciting Play of Tom Brady’s Career?

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and

The biggest heroes of the Super League’s collapse

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and

Lewandowski back in full training with Bayern

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and

The remarkable rise of Ryan Mason

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and

Why “Decriminalizing” Weed Isn’t Good Enough

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and singer Jennifer Lopez from expanding her property

Your Empty Office Turn Into Apartments?

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and singer Jennifer Lopez from expanding her property

Yeah, I Bought Some Dogecoin Today

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and singer Jennifer Lopez from expanding her property

The Pointlessness of Bribing People to Move to West Virginia for $12,000

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and singer Jennifer Lopez from expanding her property

Today Highlights

Top of the week news

5 Ways Animals Will Help You Get More

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

The Game That Finally Lets You Live Your

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

6 UX that products will have in future

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

Georgia’s Voting Law Will Make Elections Easier

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

The Last Thing Fat Kids Need Today

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

Coinbase Went Public. What and Why Is Coinbase?

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

The Communities That Live Captioning Leaves Behind

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

Why Organizers Think They Got Creamed by Amazon

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

Recommended

Top pic for you

You Don’t Have to Give Pixar Oscar Every Year

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market

Don’t Miss

Top pic for you

Enough Talk, Let's Build Something Together

Categories

Featured Posts

Featured News

Don’t miss daily news

We Now Know Who Paid $69.3 Million for Digital Artwork

Apple today named eight app and game developers receiving an Apple Design Award, each one selected being thoughtful and creative.

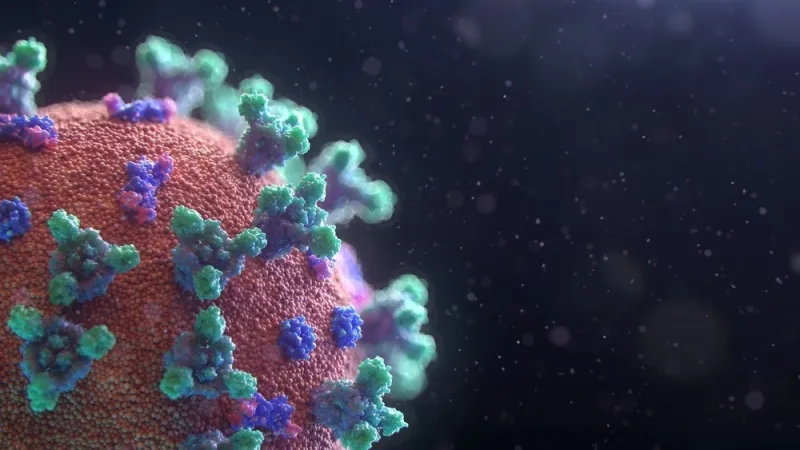

How to Catalog Pandemic History in World

Apple today named eight app and game developers receiving an Apple Design Award, each one selected being thoughtful and creative.

We’re Already Colonizing Mars Near Future

Apple today named eight app and game developers receiving an Apple Design Award, each one selected being thoughtful and creative.

Featured Video

Selected video posts

Quick Video

Weird Free Snacks Are the Only Thing to Miss About Offices

Struggling to sell one multi-million dollar home currently on the market won’t stop actress and singer Jennifer Lopez from expanding

Artist Visits Stunning Places and Paints Them Onto Trash

From crushed beer cans and broken shoes to smoke detectors! If you are going to use a passage of Lorem

We Now Know Who Paid $69.3 Million for Digital Artwork

Apple today named eight app and game developers receiving an Apple Design Award, each one selected being thoughtful and creative.

How to Catalog Pandemic History in World

Apple today named eight app and game developers receiving an Apple Design Award, each one selected being thoughtful and creative.

The Dumbest Fin Story of 2021

Joe Biden’s goal to get internet to every American is a lot tougher than it looks. If you are going

It’s Great the Government is Tightening Gambling

Even though I still hated planks at the end, my core felt tighter after doing them for 30 days straight,

Latest Posts

Black People Have Been Saying We Can’t Breathe for Decades

Apple today named eight app and game developers receiving an Apple Design Award, each one selected for

UK City Council Bans Meat at Its Events in Fight Against the Climate Crisis

Apple today named eight app and game developers receiving an Apple Design Award, each one selected for