The assistant principal held up her phone, showing me the video she’d recorded of my conversation with my brother in the parking lot after school

Micah was already outside, leaning against the passenger door, shoulders tight in that way that meant he’d been holding his breath for too long. He didn’t wave or shout—obviously. He just lifted his hands and started signing fast.

“Mom’s dialysis. Thursday. You can drive?”

I signed back automatically, like I always do with him when we talk about home stuff. It’s not even a choice for us. When it’s emotional, when it’s serious, ASL is what comes out first—cleaner, faster, truer. Spoken English feels like performing. Signing feels like breathing.

I remember the air was cold enough to sting, and the sky had that gray, drained look it gets right before winter really commits. Micah was asking if I could take Mom to her appointment because Dad had a shift he couldn’t swap. We were doing that thing we always do—assembling our family’s schedule like a fragile machine and praying nothing breaks.

And then I heard it.

“Caleb. Micah. Office. Now.”

I turned and saw Assistant Principal Kovatch standing a few yards away with her phone held up in one hand. Not like she was checking messages. Like she was aiming it.

At first I honestly thought she was filming something else. The parking lot was chaotic like always—kids weaving between cars, someone blasting music too loud, teachers waving traffic through. I didn’t think she’d be focused on two brothers standing quietly by a dented sedan, talking about kidney failure.

But she was.

She didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t look angry. That was the part that made my stomach sink. She looked… satisfied. Like she’d finally caught something.

Micah’s hands paused mid-sentence. He looked at me, brows raised: “What?”

I signed: “Stop.” Just one sharp motion.

He lowered his hands like he’d been slapped.

We followed her in.

The hallway lights felt too bright, the kind that make every surface look tired and every person look worse. Kovatch walked ahead like she already knew the outcome, like this wasn’t a conversation but a formality.

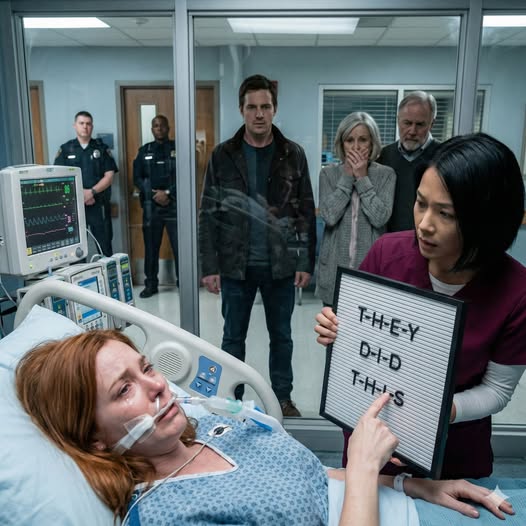

In her office, she didn’t offer us chairs right away. She set her phone on her desk, tapped the screen, and said, “Do you know why you’re here?”

I blinked at her. “No.”

She pressed play.

On the screen, there we were—me and Micah—standing by the car. Our hands moving in clear ASL. His face tense, mine focused. It looked like what it was: two kids trying to hold a family together.

Kovatch rewound it. Played it again. Then froze on a frame where my hands were mid-sign.

She tapped the screen like it was evidence in a crime show.

“Do you understand why this is a problem?” she asked.

I just stared at her. My brain kept trying to catch up. “We were talking about our mom.”

“That’s not the issue,” she said smoothly. “The issue is how you were communicating.”

Micah made a small sound in his throat—he does that when he’s angry because he can’t throw words the way hearing kids do. His hands lifted instinctively, then he stopped himself like he remembered he was being watched.

I said, “We were in the parking lot.”

“The parking lot is school property,” Kovatch replied, like she’d practiced the sentence. “Which means the communication policy applies there as well.”

“Communication policy?” I repeated.

She opened a drawer and pulled out a printed page with yellow highlights. She slid it across the desk like she was handing me a rule I’d broken on purpose.

The highlighted line said something about maintaining appropriate audible communication in all school spaces to ensure safety and inclusion.

Audible.

I read it twice, because I was sure I’d misunderstood. Then my eyes went hot.

“That’s… about yelling?” I said, even though I didn’t believe my own words. “Like, keeping noise down?”

Kovatch gave me that patient look adults use when they want you to feel childish. “It’s about ensuring staff can understand student interactions when necessary. Non-verbal communication can conceal conflict, bullying, planning unsafe behavior—”

“That’s ridiculous,” I said, and my voice cracked on the last word because I couldn’t help it.

Micah’s hands clenched in his lap.

Kovatch didn’t flinch. She lifted a pink slip from the desk. Already filled out.

“I’m assigning you detention,” she said, “for violation of the Clear Voice Standards.”

Detention.

For signing.

I felt like I’d stepped through a door into a world where gravity worked wrong.

I grew up in ASL.

That’s the part that makes this whole thing feel like a bad joke. My parents are Deaf—capital D, Deaf culture, ASL as their first language. Spoken English exists in our house like a tool in a drawer: used only when absolutely necessary, never for anything that matters.

I’m a CODA. A hearing kid of Deaf adults. Which basically means I’ve been translating the world since I could form sentences.

Some kids learn bedtime stories.

I learned how to interpret medical terms before I learned how to ride a bike.

I learned how to stand between my parents and a pharmacist and make sure they weren’t being lied to.

I learned how to watch a hearing person’s mouth move and read the intention underneath their tone, then turn it into something my parents could trust.

Our house was “loud” in its own way—stomping on floors to get attention, flashing lights, waving from room to room. Silence in our home was never empty. It was full of meaning.

So when Westfield High decided my language was a violation… it wasn’t just a rule to me.

It felt like someone telling me my family was inappropriate.

Like my parents were something to be corrected.

I tried to explain that in the office, but Kovatch had that administrative shield up. Every sentence I said slid right off.

She said exceptions were made “during instructional time” for “documented disabilities” with “assigned interpreters.”

“But Micah and I are hearing,” I said, and even as I said it I hated it—because why should hearing be the price of using our language?

“And therefore,” she replied, “you are capable of verbal communication.”

Capable.

Like ASL was a hobby I’d picked up, not the language I used to say I’m scared and I love you and Mom needs help.

Micah’s eyes were shining. He looked down, jaw tight, and I knew exactly what was happening in his head because it was happening in mine too:

If we fight back, they’ll punish us more.

If we stay quiet, they’ll erase us.

Kovatch handed me the detention slip.

“Tomorrow after school,” she said. “And I suggest, going forward, you communicate appropriately on campus.”

Appropriately.

I walked out of that office with the slip in my hand and this strange pressure behind my eyes, like my body wanted to cry but my brain refused to give it permission.

Micah followed behind me, rigid.

When we got outside again, he finally signed, small and furious:

“We can’t talk.”

That was the scariest part. Not detention. Not the write-up.

The fact that my brother looked at me and thought our language had become dangerous.

And if it could become dangerous for us, what did it mean for the Deaf kids at school? The ones who didn’t have the option to “just speak”?

Because we had a small Deaf program—maybe fifteen students total. One interpreter, Miss Russo, stretched so thin she was basically a ghost moving between classrooms, always apologizing, always late, always exhausted.

Those Deaf kids didn’t “use sign language.”

They lived in it.

So when Westfield rolled out something called “Clear Voice Standards,” dressed up as safety and inclusion… what it really meant was this:

They were trying to make the hallways hearing-only.

They were trying to make Deafness quiet.

And I realized, standing there in the cold parking lot with a pink detention slip in my hand, that this wasn’t going to be a one-time misunderstanding.

This was a policy.

A system.

And systems don’t stop unless you make them.

That night at home, my dad didn’t get angry the way hearing parents do—no shouting, no slammed doors.

He got angry in ASL.

Which is… scarier, honestly, because Deaf anger is sharp. It’s facial expression and speed and precision. It’s your whole body saying, this is unacceptable.

Micah and I sat at the kitchen table while Mom rinsed dishes with slow, tired movements. The dialysis days always left her drained, like someone had scooped the energy out of her and forgotten to put it back.

I explained what happened, signing carefully so I wouldn’t miss anything. I showed Dad the slip. I repeated Kovatch’s words.

“Parking lot is school property.”

“Audible communication.”

“Safety and inclusion.”

Dad’s eyebrows climbed higher and higher, and then his hands started moving fast.

“They punished you for signing?”

“They punished Micah?”

“At school with Deaf students?”

Mom turned from the sink, her wet hands lifted midair like she’d forgotten what she was doing. Her face didn’t harden like Dad’s. Hers… folded. Like worry had lived in her for so long it knew exactly where to sit.

She signed something small:

“They think we’re wrong.”

That was the punch.

Not the detention. Not the policy.

That thought—my mom, apologizing to herself without even meaning to.

I shook my head hard and signed back:

“No. We’re not wrong.”

But the truth is, I didn’t feel certain yet. I felt shaky. Because when a school writes something down, prints it, highlights it, and calls it “standards,” it can make you doubt your own reality.

The next morning, the hallways felt different.

Not physically. Same lockers. Same posters about spirit week. Same smell of cheap disinfectant and cafeteria grease.

But the eyes were different.

Monitors stood in places they didn’t usually stand. Clipboard in hand. Watching like they were waiting for someone to slip.

And once you know you’re being watched, you start moving like your body is guilty even if your brain says you’re not.

Micah and I met at my locker before first period. He didn’t sign immediately. He looked around first.

That alone made my throat tighten.

We walked toward class, shoulder to shoulder, and he whispered, barely audible, “So… Thursday… about Mom…”

It sounded wrong. Like he was wearing someone else’s voice.

I whispered back, “We’ll figure it out later.”

It was the first time in my life I had avoided talking to my brother about our mother’s health.

Not because I didn’t want to.

Because I was afraid of getting caught communicating in our own language.

That’s what the policy did within twenty-four hours. It didn’t just punish behavior. It changed how we existed.

By lunch, I’d already seen it happen twice.

Two Deaf sophomores—Laya Brenner and Jordan Kim—were at the lockers signing about chemistry homework. Nothing dramatic. Just casual conversation, the way everyone talks between classes.

A parent volunteer monitor approached them like they were doing something inappropriate.

“Stop using hand gestures,” she said loudly, like Deafness was something you could shame people out of. “Speak normally.”

Laya pointed to her ears and shook her head, then signed slowly, clearly: DEAF.

The monitor frowned, annoyed, like Laya had refused to cooperate.

“You can read lips,” she insisted. “You can vocalize. You need to make an effort like everyone else.”

Jordan didn’t even bother trying to lip-read her. He kept signing to Laya, and the monitor’s face went tight with that righteous power adults get when they think rules make them morally superior.

She wrote him up.

Right there, in front of everyone.

Jordan’s hands dropped mid-sentence, and the look on his face… I’ll never forget it. It wasn’t anger at first.

It was fear.

Real fear.

Because Jordan knew what we all knew now: the school had just criminalized his language.

And if your language becomes a “behavior problem,” then your identity becomes something that can be disciplined out of you.

The policy worked like a three-strike system, and everyone learned that fast.

First strike: warning, counselor meeting.

Second: detention, behavior contract.

Third: suspension, possible “defiance” escalation.

Every strike went into your record.

The part that made me sick was how official it sounded. Like they were tracking violence instead of tracking hands.

Within the first week, Deaf kids stopped talking in the hallways. You could see them—standing in groups but quiet, hands still, eyes darting around.

They’d moved from living freely to surviving.

And for Micah and me, the experience was this weird double-layer of hurt.

Because we could technically “comply” by speaking.

But every time we did, it felt like betraying home.

The policy turned ASL into something shameful, like it belonged only behind closed doors.

And that’s how discrimination always works best—when it convinces you to self-censor.

Then came my detention.

I sat in a classroom after school with kids who’d been caught vaping, skipping, fighting. The teacher supervising didn’t know what to do with me.

She glanced at my slip and frowned. “Using… sign language?”

I nodded, jaw tight.

She looked uncomfortable. “Well. Just… don’t do it again.”

Like it was chewing gum.

Like it was a bad habit.

I went home feeling humiliated in a way I couldn’t explain to anyone who hadn’t grown up bilingual in a language people love to treat as “optional.”

Micah got his second strike before Halloween.

A substitute caught him signing with me near the library. We were talking about whether Mom’s appointment needed to be canceled because she’d been vomiting all morning. Real life stuff. Scary stuff. The kind of stuff you don’t want to say out loud in a hallway full of strangers.

The sub didn’t even speak to us first. Just pulled out a phone, recorded, and sent it to the office.

Micah’s detention meant he missed the ride home. Which meant I took Mom to dialysis alone. Which meant Dad had to adjust his shift. Which meant our fragile family schedule snapped like a rubber band.

And then, as if the school needed to add insult to injury, Micah came home with an essay prompt from detention:

Explain how verbal communication promotes safety and inclusion.

I swear to God, I stared at it and felt heat rise behind my eyes.

Micah looked nauseous. “They want me to write this,” he whispered.

Dad signed furiously from the other side of the room, and Mom’s face pinched with quiet pain.

So Micah wrote what they wanted.

He wrote the safest, most obedient version of himself. He repeated their buzzwords. He faked agreement.

And while I helped him edit it into something that wouldn’t get him punished again, I felt something shift in me.

Because it wasn’t just that they were punishing us.

They were trying to make us participate in our own erasure.

The next week, my counselor—Dr. Felton—called me in.

He sat across from me with that “supportive professional” face that always feels like a mask.

“Caleb,” he began, “I want to talk about your adjustment to the Clear Voice Standards.”

Adjustment.

Like my language was a disorder.

He asked about my home life. He asked if it was “challenging” communicating with Deaf parents.

I wanted to laugh, but I couldn’t. It wasn’t funny. It was exhausting.

“We communicate fine,” I said. “The problem is the school.”

He nodded, like he understood, and then said, “The school needs consistent standards for everyone. Exceptions undermine the policy.”

Then he slid a behavior contract across the desk.

It required me to commit to spoken English on school property, submit to “random compliance checks,” and meet bi-weekly to discuss my “progress.”

I stared at the paper, my hands starting to shake.

This wasn’t support.

This was probation for being who I was.

I brought it home, and when I interpreted the contract for my parents, my dad’s face went pale. Not because he didn’t understand the words.

Because he understood the message.

Your family is a problem here.

Mom cried silently.

Not loud sobs. Just tears that fell and didn’t stop, like her body was apologizing for something she never did.

And that’s when I knew—I mean really knew—we couldn’t just “wait it out.”

Because if we stayed quiet, this would become normal.

And if this became normal, Deaf kids at Westfield would spend their entire school lives being punished for speaking.

I sat at the kitchen table that night, staring at the contract, and felt something hard and clear form inside me.

A decision.

If the school wanted a fight, they’d picked the wrong kid.

Because I wasn’t just defending myself.

I was defending my family’s language.

And once that becomes personal, it stops being scary.

It becomes inevitable.