At the funeral, my grandpa left me his chess book.my mother threw it in the trash: “it’s junk. get this out of my sight.” i opened the pages and went to the bank. the loan officer turned pale: “call the fbi – she doesn’t own the house”

The first time I heard the words “Call the FBI,” I was sitting in a bank office with a dripping chess book in my lap.

The loan officer stared at the notarized pages I’d just slid across his desk. His face, tanned and bored a second earlier, went the color of old paper. On his screen, I saw my mother’s name, my grandfather’s address on the New Jersey coast, and a pending line of credit for $500,000 using the house as collateral.

He swallowed, tapped a key, then another. “Ms. Vance,” he said quietly, eyes still on the monitor, “who gave you this will?”

“My grandfather,” I answered. “Right before he died.”

He finally looked up. Whatever he saw in my expression convinced him I wasn’t there to play games. His chair scraped back. He stuck his head out the door and called for his supervisor. “You need to see this,” he murmured. “And get fraud on the line. If this is real, she doesn’t own the house.”

That was the moment the board flipped.

But if you really want to understand how a ruined chess book turned my family’s dream house into a crime scene, you have to go back to the day we buried the only person who ever taught me how to think three moves ahead.

—

My name is Hannah Vance, and for most of my life I was treated like background noise in my own home.

We called it Cliff House, a shingled gray estate perched on a bluff above the Atlantic in Cape May County, New Jersey. Tourists took pictures of it when they walked the public beach below, pointing at the columned porch and the terraced garden that fell toward the water. To strangers, it looked like a place where old money took its martinis at sunset.

To me, it was a very pretty cage.

My grandfather, Nicholas Vance, had bought the property in the seventies with manufacturing money and stubborn ambition. He was the kind of man who wore the same navy cardigan for thirty years and drove the same truck until the wheels begged for mercy. He believed in two things: compound interest and the power of the quiet move.

He taught me both at the kitchen table.

While my mother, Brenda, floated through charity luncheons and spa days, and my older brother, William, learned how to golf deals closed, Grandpa taught me how to read balance sheets and chess boards. He’d sit with a chipped mug of Earl Grey and say, “Hannah, the piece that wins isn’t always the one making all the noise. Watch the pawns. Watch who’s moving them.”

So of course, on the day we buried him, the last thing he left behind that belonged specifically to me looked small and unimpressive.

A smoke-scented, leather-bound chess book.

The funeral reception had stretched on for hours. The house smelled of lilies and expensive perfume, layered over old wood and sea damp. Caterers in black moved like ghosts through the mahogany-paneled rooms. People I barely knew squeezed my hand and told me what a great man Nicholas had been while scanning the crown molding like they were mentally appraising it.

I moved among them refilling wine glasses and gathering empty plates, my black dress already streaked with Merlot and gravy. No one questioned why the granddaughter of the deceased was busing tables. They were used to seeing me with a tray in my hands.

By the time the last guest’s Lexus rolled down the driveway, the late-afternoon light had gone thin and gray. A handful of staff quietly disappeared toward the back entrance. The florist’s van pulled away. The house exhaled.

That was when my mother finally let her real face show.

Brenda took her throne at the head of the dining table, a crystal flute in one hand and a property appraisal in the other. At forty-nine, she still wore grief like a designer label—black sheath dress, diamonds at her throat, mascara that never dared to smudge. Across from her sat a man in a slim gray suit I didn’t recognize.

He had the posture and expression of a developer—the kind of person who looked at a garden and saw square footage.

William lounged on the sideboard, his tie loosened, scrolling his phone one-handed. He didn’t glance up when I stepped into the doorway.

“Mom,” I said softly. “Can I ask you something?”

She didn’t immediately look at me. She was busy tracing a pen along the bottom line of the appraisal, lips moving as she read the numbers. I heard phrases like “tear-down potential” and “coastal luxury townhomes.” My stomach tightened.

Finally, she flicked her gaze toward me, irritated that the help had spoken out of turn.

“What, Hannah?” she sighed.

I clasped my hands together so she wouldn’t see them shake. “I was wondering if I could have Grandpa’s chess book. The one on the mantle in the library. He taught me to play from it.”

For a few seconds, no one said anything. The developer glanced at me, then quickly back at his papers, already bored. William smirked at his reflection in the dining room mirror.

Brenda followed my glance toward the library doorway, where the dark rectangle of the mantle was just visible. The book in question sat on the edge, its cracked leather spine facing the room like an old soldier at attention.

“That dusty thing?” she said. “It smells like smoke and mothballs. Nicholas should have thrown it out years ago.”

She rose in one fluid motion, heels clicking against the parquet. For a breath, hope flared in my chest. Maybe she’d softened. Maybe the funeral had actually reached whatever organ passed for a heart in her chest.

She walked into the library, plucked the book off the mantle, and came back into the dining room holding it between two manicured fingers like it was contaminated.

“Here,” she said.

Then she dropped it onto the hard wooden chair beside her at the head of the table.

Before I could move, she turned and slid into the chair, settling her weight directly on top of the book. Leather squeaked against wood.

On my grandfather’s memory.

“This table is too low,” she said lightly, hitching her skirt as she adjusted. “I need the extra height for negotiation. Otherwise, I’m staring up at him all afternoon.” She nodded toward the developer, who chuckled politely.

William barked out a sharper laugh. “Best use of that book I’ve seen,” he said.

He lifted his champagne flute like he was toasting Grandpa and then “accidentally” tipped it. A stream of sticky gold liquid splashed onto the seat, seeping into the leather pressed beneath Brenda’s tailored suit.

“Oops,” he said.

They didn’t look at me. They just kept talking about bulldozing the rose garden to put in a pool and leveling the carriage house to create more parking for future buyers.

My nails dug crescents into my palms. I could taste metal at the back of my throat.

In that moment, they weren’t just sitting on a book. They were sitting on the only part of my grandfather that hadn’t yet been parceled, appraised, and assigned a dollar amount.

“Go see if the caterer left any decent champagne,” Brenda said without glancing my way. “This is flat.”

Dismissed.

That was the second time that day I watched someone bury my grandfather.

—

I waited.

I waited while they argued over zoning permits. I waited while the developer explained how many units they could squeeze on the lot “without upsetting the neighbors too much.” I waited until Brenda’s voice softened into the syrupy tone she used when she smelled money and William’s laughter got a half-octave louder.

Only when they finally drifted out to the patio to smoke cigars did I move.

The glass door clicked shut behind them. Their reflections hovered in the glass, small and separate from the vast gray ocean beyond. I listened to their voices fade under the wind.

Then I walked straight to the head of the table.

The chair was still warm when I pulled it back. The book slid off the seat and onto the floor with a heavy thud. Champagne dripped from the spine. The leather was stained a dark, ugly brown.

I picked it up carefully, like he might feel it wherever he was.

Up close, it smelled like his den—tobacco, dust, and the faint tang of Earl Grey. The gold lettering on the cover was almost worn away, but I could still make out the title: “Endgames and Quiet Sacrifices.”

Of course.

I carried it into the kitchen, my pulse hammering, and laid it on the cool marble counter. With shaking hands, I dabbed at the champagne with a dish towel, trying not to smear the ink of his marginal notes.

When I eased it open, I expected to find the familiar columns of diagrams and scribbled annotations.

Instead, after the first few printed pages, there was a gap.

The middle of the book had been carved out.

Someone—my grandfather, I realized with a jolt—had hollowed a rectangle from the pages as cleanly as if he’d used a scalpel. Nestled inside the cavity, wrapped in a plastic sleeve, lay a thick document folded in thirds.

My breath left my body in one hard rush.

I slid the document out and unfolded it on the counter.

At the top, in heavy black ink, was my grandfather’s name: NICHOLAS EDWARD VANCE.

Below it, in the sober language of lawyers, was the phrase that would change everything: LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT.

I scanned the first page, then the second, my eyes skimming past the legal boilerplate to the parts that mattered.

He had signed it two years earlier, in front of a notary and two witnesses. The notary’s seal was crisp and raised under my fingertips.

And buried halfway down page three was a sentence I read three times before my brain believed it.

“I hereby devise and bequeath the property known as Cliff House, together with all land, improvements, bank accounts associated with said property, and investment portfolios held in my name, to my granddaughter, Hannah Elaine Vance, in fee simple absolute.”

My name.

Not my mother’s. Not my brother’s. Mine.

I kept reading, past the distribution of a few small cash gifts to charities and former employees, past the line where he explicitly revoked all prior wills.

Near the end, another paragraph caught my eye.

“In the event that any beneficiary shall initiate proceedings or execute documents that challenge the mental capacity of another beneficiary for the purpose of seizing control of assets, said accuser shall submit to an independent forensic psychiatric evaluation and sworn polygraph examination, the results of which shall be admissible in any proceeding related to this estate.”

I didn’t understand the significance of that clause yet.

I would.

What I understood in that kitchen, with champagne drying on my hands and funeral flowers wilting in the next room, was simpler.

My grandfather had left everything to me.

My mother didn’t know.

And she had just been sitting on the evidence.

For a second, the childish part of me surged up, wild and hot. I pictured storming out onto the patio, slamming the will down on the glass table between their cigars and brandy, and screaming, “You don’t own this house. I do.”

I pictured the look on Brenda’s face, the way her fingers would claw for the papers, how William’s laughter would die in his throat.

The fantasy lasted seven seconds.

Then the part of me my grandfather had spent years training took over.

If I walked out there and waved this will around like a flag, I could ruin it in one impulsive move.

Brenda would snatch it. She’d shred it, burn it, or claim it was forged. Even if I managed to keep my hands on it, she’d hire attorneys who billed more per hour than I made in a month, and we’d be locked in probate court for years.

It would be my word against hers in a civil dispute.

Civil court wasn’t enough.

“These are people who only believe in consequences when they’re in handcuffs, Hannah,” my grandfather had said once, watching Brenda argue with a contractor over a bill she had no intention of paying. “You don’t lecture a shark about morals. You just make sure there’s a bigger boat watching.”

I stared at the will.

I didn’t just want the house.

I wanted the bigger boat.

I slid the will back into its plastic sleeve and tucked it into the hollowed-out book. I closed the cover and slipped the book into my tote bag under my spare sweater.

Then I wiped the counter until there was no trace of champagne or dust.

I walked back onto the patio with empty hands and a neutral face, collected their glasses, and listened.

Greed would set the trap.

Silence would be the bait.

—

The next morning, after Brenda left for a “grief massage” and William disappeared in his leased Mercedes, I took the bus into town.

I could have driven one of the family cars, but keys had a way of migrating off the hooks when I touched them. Besides, the bus was anonymous. Just another girl in black sitting by the window, hugging a tote bag as if it held her only future.

Cape May’s main street still wore its off-season quiet. The tourist shops were closed, their windows filled with dusty seashell displays and SALE signs that had seen too many summers. The sky was the flat, pewter color of dishwater.

I got off in front of Shoreline Community Bank.

Inside, the air smelled like carpet cleaner and printer toner. A row of retirees sat in plastic chairs waiting to talk about CDs. Behind the counter, tellers in navy polos smiled with the stiff politeness of people who’d been told to smile.

I approached the information desk, where a woman with a silver bob and a name tag that read CAROL looked up.

“Can I help you?” she asked.

“I need to speak to someone about an estate,” I said. “And a pending loan. It’s urgent.”

Her gaze dipped to the chess book clutched against my chest, then back to my face. Something in my expression must have convinced her this wasn’t about overdraft fees.

“Let me see who’s available,” she said.

Five minutes later, I found myself in a glass-walled office across from a man in a navy suit with a receding hairline and a Rutgers mug on his desk.

“I’m David Patel,” he said, extending his hand. “Senior loan officer. Carol said you have concerns about a loan tied to an estate?”

I set the chess book on his desk, opened it, and slid the will across the polished wood.

“My grandfather was a client here,” I said. “Nicholas Vance. He passed away last week. I just found this in his belongings. I think my mother is trying to borrow against the house using falsified documents.”

He started to give me the sympathetic-bank-officer face, the one they probably practiced in training. Then he saw my grandfather’s name and the raised notary seal.

The expression froze.

He turned to his computer, fingers flying over the keyboard. “Give me a second,” he murmured.

On the other side of the glass wall, the bank moved in slow motion—people signing deposit slips, a kid tugging on his mother’s sleeve, Carol stapling something. Inside the office, the air seemed to thin.

Patel clicked through several screens, his brow furrowing deeper with each one.

“Ms. Vance,” he said, voice lower now, “has anyone else contacted you about this estate? Attorneys, other family members?”

“My grandfather’s lawyer read a will at the house two days ago,” I said carefully. “It was different from this one. It left the property to my mother and brother jointly. There was no mention of me owning the house.”

He swallowed. “Do you have a copy of that version?”

“No,” I said. “They said it was going straight to the courthouse for probate.”

He nodded grimly and clicked one last time.

A new screen popped up, filled with numbers and lines of text I couldn’t quite decipher from across the desk. But I saw my grandfather’s address and my mother’s name.

“Your mother applied for a $500,000 line of credit yesterday,” he said. “Secured by a deed stating she is the sole owner of Cliff House.”

The number hit my chest like a physical weight.

Half a million dollars.

“That can’t be legal,” I whispered.

“If this document”—he tapped the will with one finger—“is valid and more recent than whatever was filed with the county clerk, then no, it’s not legal.” He pushed his chair back so fast it bumped the credenza behind him.

He opened his office door and jerked his chin at Carol. “Get Maria from compliance. Now. And see if Frank from fraud is on-site.”

“Is everything okay?” she asked.

“No,” he said. “If this is what I think it is, we may need to contact federal authorities. The borrower may not own the collateral.”

He turned back to me, eyes serious now. “Ms. Vance, I need you to sit tight. Don’t confront your mother. Don’t mention this to anyone. Do you have an attorney you trust?”

“I… know my grandfather’s estate lawyer,” I said. “We’re not exactly on speed dial.”

He scribbled a name and number on a yellow sticky note and slid it toward me. “Keep that will with you at all times. Make an appointment with the estate attorney today. And if your mother tries to drag you into any signing related to this property, you call this bank and you call him.”

On the top of the note, above the attorney’s name, he wrote three letters: FBI.

The bigger boat had just appeared on the horizon.

—

The estate attorney’s office was on the second floor of a brick building downtown that smelled faintly of copier toner and old coffee. His name was Robert Vance—no relation, he assured me with a thin smile when I raised an eyebrow. Just another Vance in a county full of them.

He’d handled my grandfather’s corporate contracts for decades and, apparently, Brenda’s divorce from my father. I had not been invited to that meeting either.

When I laid the hollowed-out chess book on his desk and unfolded the will, the boredom peeled off his face like a mask.

“Where did you get this?” he asked.

“From the chess book Grandpa used to teach me,” I said. “My mother tried to use it as a booster seat yesterday. I took it to the kitchen to dry it off and found this.”

He read silently, lips moving. When he hit the clause about me inheriting Cliff House and the assets, his brows shot up. When he reached the competency clause near the end, his eyes sharpened.

“Well,” he said finally, sitting back. “Nicholas always did like a good gambit.”

He turned to his computer, pulled up the county’s probate filings, and swore under his breath.

“Your mother filed a different will the morning after the funeral,” he said. “Dated five years ago. It leaves the house to her and William, with you receiving a token cash gift. That explains why I wasn’t asked to read it. I didn’t draft that version.”

“So that one is fake?” I asked.

“Could be forged. Could be a previous will they dug out of a drawer because they preferred it. Either way, this one—” He tapped the chess book will. “—is more recent. And it revokes all prior documents. Legally, this is the controlling instrument.”

All I heard was: I wasn’t crazy.

I wasn’t invisible in my grandfather’s eyes.

“So what happens?” I asked. “Do we just… walk into court with this and tell the judge my mother lied?”

He gave me a look that said I’d just suggested we solve a chess problem with a hammer.

“We could challenge the probate,” he said slowly. “But your mother has resources. So does your brother. They could drag things out for years.”

“I don’t care if it takes years,” I said. “I’m not letting them steal his house.”

“It’s not just about time,” he said. “It’s about leverage. Right now, it’s a civil dispute. You’re alleging misconduct in probate. She’s alleging you’re disgruntled and unstable. The judge would split the difference or tell you to work it out in mediation. Nicholas didn’t think like that. Neither should we.”

I thought of the clause about challenging someone’s competence.

“What did he think?” I asked.

Vance steepled his fingers. “Nicholas believed your mother and brother would eventually overplay their hand. He told me more than once that if they were going to steal, they’d go big. Mortgage scams, fraudulent sales, that sort of thing.”

A cold shiver walked down my spine. “They’re already trying to borrow half a million using a fake deed.”

He nodded once. “Then we let them.”

I stared at him. “We what?”

“If we go to the bank now, they’ll freeze everything, cancel the loan, and chalk it up as a misunderstanding,” he said. “Your mother will cry, blame it on grief and confusion, and we’ll be back to civil court. But if we let her sign, if we let her falsely represent herself as the sole owner of the property on federally regulated loan documents, then it’s no longer just a family fight.”

“It’s fraud,” I whispered.

“Bank fraud,” he said. “Wire fraud, if funds cross state lines electronically. Those are federal crimes. With the right cooperation from the bank and the U.S. Attorney’s Office, we can set up a sting. Catch her in the act. Once that happens, the probate judge isn’t weighing competing stories. He’s looking at a convicted felon who tried to steal from her own father’s estate.”

My mouth felt dry. “And me?”

“You’re the sole beneficiary named in the valid will,” he said. “If we do this right, you won’t just keep the house. You’ll have it free of her claims, with a clean title and a record that shows Nicholas anticipated exactly this kind of stunt.”

He slid a consent form across the desk. “But Hannah, you need to understand something. Once we set this in motion, there’s no halfway. If your mother and brother sign those papers, they could go to prison. This won’t be a scolding. It will be prosecution.”

In my mind, I saw my mother sitting on my grandfather’s book, laughing as champagne soaked into his notes. I heard William’s voice as he told the developer to bulldoze the garden Grandpa had spent forty years tending.

I remembered the way they never looked at me unless they needed something ironed, cooked, or scrubbed.

“Grandpa didn’t hollow out a chess book just to scare them,” I said quietly. “He wanted them stopped.”

Vance held my gaze for a long beat, then nodded.

“All right then,” he said. “We let the sharks swim straight into the net.”

He picked up his phone. “But before we call the bank’s fraud department back, I want you to do one thing.”

“What?”

“Go see a psychiatrist.”

I blinked. “Excuse me?”

His mouth quirked. “You saw the competency clause. Nicholas knew exactly what your mother’s favorite move would be once she realized he left everything to you. She’s going to claim you’re unstable. That you’re imagining things, planting documents, whatever story plays best. She’ll find some friendly doctor to sign a piece of paper saying you shouldn’t manage your own affairs.”

“Like a guardianship,” I said slowly.

“Exactly,” he said. “So before she can do that, we’re going to get ahead of her. I’ll schedule you for a full forensic evaluation with Dr. Michelle Evans, the state’s chief psychiatrist. It’ll be thorough. It won’t be fun. But when she’s done, you’ll have a report that says you are competent to manage your estate. When your mother shows up waving her bought-and-paid-for affidavit, we’ll have something better.”

“Like bringing a queen to a pawn fight,” I murmured.

He smiled faintly. “Nicholas would have liked you quoting chess at a moment like this.”

—

Two weeks later, the trap began to close.

I was in the sunroom polishing windows that didn’t need it, my reflection ghosted over the Atlantic. The February light made everything look washed out—the lawn, the bare rose bushes, the woman pacing in the study behind me.

Brenda’s heels clicked a metronome of anxiety against the hardwood.

“This is ridiculous,” she snapped, waving a letter in William’s face. “The developer says his lender is nervous about the title. They want more documentation. I told him it was simple, but he’s acting like we’re hiding bodies on the property.”

William lay sprawled on the leather sofa, phone in hand, shoes on an ottoman my grandfather never let us touch. “So you tell him to relax,” he said. “We’ve got the deed. We’ve got the appraisal. It’s a bluff to lower the price.”

“This letter is not a bluff,” she hissed, thrusting it toward him again. “He’s delaying the closing. I have bills due, William. Atlantic City doesn’t forget.”

There it was.

The debt I wasn’t supposed to know about.

I kept my rag moving in small circles, each swipe another beat of my pulse.

William finally dragged his eyes off his phone. “Then get a bridge loan,” he said. “I know a guy who does hard money. He doesn’t ask too many questions as long as you’ve got something pretty to put up as collateral.”

“Like the house,” Brenda said slowly.

“Exactly,” he said. “We take out, say, $500,000—enough to clean the slate and get you breathing room. We pay his insane interest for a month or two until the developer’s lender stops being a baby and the sale goes through. Then we pay off the hard money and pocket what’s left.”

“Five hundred thousand,” she repeated, the number stretching out like a spell.

I watched her greed physically smooth the worry lines from her forehead.

“I don’t care about the interest,” she said. “Set it up. Friday. I want that money in my account by the weekend.”

I wiped one last imaginary smudge from the glass and carried my bucket out of the room, heart beating hard enough to rattle my ribs.

In the laundry room, I closed the door and pulled my phone from my apron pocket.

The number for Robert Vance was burned into my brain by then. I didn’t need to look at the sticky note.

He answered on the second ring.

“It’s happening,” I whispered. “They’re taking out a hard money loan. Five hundred thousand. Using the house as collateral. They’re signing on Friday.”

He was silent for a heartbeat. When he spoke, his voice sounded like steel. “Are you absolutely sure?”

“I heard them,” I said. “He’s ‘got a guy.’ She’s desperate. She can’t resist that kind of cash.”

“Then we’re done waiting,” he said. “I’ll call the bank and the U.S. Attorney’s Office. Do exactly what you’ve been doing. Keep your head down. Let them think you’re not paying attention.”

I looked at my reflection in the stainless-steel washing machine door.

I didn’t look like an heiress.

I looked like the maid.

“Let them sign,” I said.

—

Friday morning arrived with the suffocating stillness of a courtroom before the verdict.

The sky over the ocean was low and heavy, the kind of gray that made it hard to tell where the water ended and the air began. The house felt too big and too small all at once.

I had spent two days scrubbing baseboards and polishing banisters that didn’t need it, moving through the house like a Roomba with anxiety.

I needed Brenda and William to see me exactly the way they always had.

As part of the furniture.

At ten on the dot, the doorbell chimed.

I opened it to a man in his fifties with a tan line where his sunglasses usually sat and a suit that looked more expensive than it fit.

“I’m Mark Henderson,” he said, flashing a business card from Shoreline Capital Partners. “Here to meet with Mrs. Vance about a loan.”

His smile was a little too eager. His briefcase was a little too shiny.

Behind him stood a woman in a navy blazer carrying a leather bag embossed with the state seal. Her notary stamp bulged under the flap like a concealed weapon.

“Right this way,” I said, as if I were taking a tray of hors d’oeuvres to the dining room.

They set up in my grandfather’s library, because of course they did. The mahogany desk where he used to lay out chess puzzles now held stacks of legal papers and Henderson’s sleek laptop.

Brenda swept in wearing a cream silk blouse and a smile that didn’t reach her eyes. William followed, smelling like cologne and entitlement.

I brought in a silver tray with coffee and biscuits, keeping my head bowed.

If Brenda noticed that my hands weren’t shaking, she didn’t comment.

“So,” she said, settling into the leather chair behind the desk. “Once I sign, the funds are released?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Henderson said, fingers flying over his keyboard. “As soon as we execute the promissory note and deed of trust, and my associate notarizes them, the wire for $500,000 will hit your account within minutes. I do have to stress the interest rate is aggressive. It’s not a product we offer lightly.”

“We won’t be carrying it long,” William cut in, leaning over her shoulder. “The property’s already under contract with a developer. This is just a bridge. We have plenty of equity.”

He was lying. The developer had already backed away from the deal the minute his people sniffed around the title.

They weren’t borrowing to bridge anything.

They were borrowing to run.

“Standard procedure,” Henderson said smoothly. He slid a stack of papers across the desk. “Initial here and here, Mrs. Vance. Sign on the last page. This is the deed of trust, pledging the property at 117 Cliff House Road as collateral. This”—another stack—“is the loan application and affidavit of ownership.”

Ownership.

The word sat on the table between them like a loaded gun.

I poured coffee into their cups, stretching the simple action as long as I could. I wanted to see it. I needed to witness the exact moment intent became action.

Brenda picked up the pen. Her hand didn’t tremble.

She didn’t look at the portrait of my grandfather hanging on the wall behind the desk. She didn’t glance toward the doorway where I stood with my tray. She just bent over the papers and began to sign.

“Brenda L. Vance,” she wrote in looping script on the deed of trust.

She signed the promissory note.

She signed the affidavit swearing, under penalty of perjury, that she was the sole owner of Cliff House.

With every stroke of ink, she dug herself deeper into a hole there was no ladder out of.

The notary checked her ID, stamped each document with a heavy thud, and dated them.

Each stamp sounded like a gavel.

“Congratulations,” Henderson said, turning the laptop slightly so Brenda could see the screen. “I’m initiating the wire now.”

A cheerful chime blipped from his speakers.

“There we go,” he said, grinning. “Transfer complete. $500,000 wired to the account ending in 1432.”

Brenda let out a sound that was half laugh, half sob. “We did it,” she breathed, gripping William’s arm. “We’re free.”

William was already pulling his phone from his pocket. “Told you,” he said, puffing his chest. “Easy money.”

In my apron pocket, my phone vibrated once.

The text was simple: We are in position. Audio?

I had been on a muted call with Robert Vance for the last ten minutes.

He was sitting in a sedate sedan at the end of the driveway with several unmarked SUVs behind him.

The bigger boat was a lot closer than they realized.

I took a breath and let my hands shake just a little as I stepped forward.

“Mom?” I said.

She turned, annoyed. “What, Hannah?”

“Did it go through?” I asked. “The money. Is it really in your account?”

Her annoyance sharpened into contempt. “Of course it is,” she snapped. “This is my house. My money. You don’t need to worry your little head about it. Now get out of my sight before I have security throw you out.”

There was no security.

Just me.

But that line would sound excellent in court.

I took my phone out of my pocket and tapped the screen.

“Mr. Vance,” I said, my voice steadying. “Did you get all that?”

His reply crackled through the speaker on speakerphone, clear enough for everyone in the room to hear.

“Loud and clear, Hannah,” he said. “Step away from the desk.”

I moved to the side.

The front door didn’t open.

It exploded inward.

—

The first agent through the door wore an FBI windbreaker and the expression of someone who had no interest in family drama, only crime scenes. Three more followed, weapons holstered but hands ready. Behind them came a woman in a navy suit I recognized from my research as the county’s district attorney.

“Federal agents,” the lead officer barked as they swept into the library. “Step away from the desk. Hands where I can see them.”

For a second, everyone went perfectly still.

Then the room detonated.

Brenda lurched to her feet, knocking over her chair. Her coffee cup toppled, shattering on the rug and splashing dark liquid across her expensive shoes.

“What is this?” she screeched, pointing a shaking finger at the agents. “Who are you? Get out of my house!”

“It’s not your house,” I said.

My voice sounded calm to my own ears, like it belonged to someone who had rehearsed this moment in a thousand insomnia-fueled nightmares.

All eyes swung to me.

I reached into my tote bag and pulled out the chess book. My fingers didn’t fumble.

“This is,” I said.

I opened the book, slid the will free, and handed it to the lead agent.

“This is my grandfather’s original, notarized last will and testament,” I said. “It leaves Cliff House and all associated assets to me, Hannah Elaine Vance. My mother just used a forged deed to secure a $500,000 loan against property she doesn’t own. That’s wire fraud. That’s bank fraud.”

The agent scanned the first page, then the signature, then the notary seal.

His jaw tightened.

Behind him, Henderson had gone from smug to sheet-white. “She told me the title was clean,” he blurted, grabbing his laptop like a life raft. “I have the emails. She said the probate was just a formality. I’m not going down for this.”

“You can explain that to the judge,” the agent said without looking at him. Another officer gently but firmly took the laptop from Henderson’s hands.

The lead agent stepped toward Brenda.

“Brenda Louise Vance,” he said evenly. “You are under arrest for wire fraud, bank fraud, and making false statements to a federally insured financial institution.”

He turned her around and clicked handcuffs around her wrists.

The sound of metal locking closed was better than any inheritance.

“You can’t do this,” she gasped. “I am Brenda Vance. This is my house.”

“Not today,” I said.

She twisted to glare at me over her shoulder, mascara finally starting to smear. “You ungrateful little witch,” she spat. “You’ve always been sick. You don’t know what you’re doing.”

I’d been waiting for that word.

Sick.

The room went cold.

“Officer, wait,” another voice cut in.

William.

He had been very quiet for the last thirty seconds, which should have been my first clue he was about to try something outrageous.

He stepped forward, smoothing his blazer with a theatrical little tug, and opened his leather briefcase.

“You’re arresting the wrong person,” he said.

“Back up, sir,” the lead agent warned.

“I’m afraid I can’t,” William said.

He pulled out a document with a heavy-looking embossed seal and held it up like a shield.

“This is an emergency guardianship order issued this morning by Judge Miller of the county probate court,” he announced, his voice taking on the smug tone he used when he thought he was the smartest person in the room. “It declares my sister, Hannah, legally incompetent to manage her affairs due to severe paranoid delusions and a history of fabricating evidence. As of nine a.m. today, she is a ward of the state. I am her legal guardian.”

The words hit me like someone had opened a hatch under my feet.

Guardianship.

The exact move Robert had predicted.

The agent took the document, frowning as he scanned it. Another agent leaned over his shoulder.

“It’s got a judge’s signature,” the second agent murmured.

“That order invalidates any accusations she’s making,” William pressed on. “She’s sick. She’s been sick for years. She imagines conspiracies. She plants things. You can’t rely on anything she says or produces.”

Brenda stopped struggling. A cruel smile flickered back across her face. “I told you,” she hissed at me. “You’re sick. You’ve always been sick.”

For ten long seconds, the only sound in the room was the grandfather clock in the corner, ticking out my future.

If the agents accepted that order at face value, everything could unravel.

The will could be called into question.

The arrest could be paused.

They could ship me off to some facility while Brenda and William found a new way to strip-mine my grandfather’s legacy.

I looked at Robert Vance.

He didn’t look panicked.

If anything, he looked almost bored.

“Officer,” he said calmly, stepping forward. “Before you enforce that order, you might want to read the addendum to the will Ms. Vance just handed you. Clause fourteen, subsection B.”

The agent flipped to the back pages, lips moving as he read.

“The competency clause,” Robert supplied. “Nicholas anticipated precisely this tactic. He specified that any beneficiary who challenges another beneficiary’s mental state to gain control of assets must submit to an independent forensic psychiatric evaluation and a sworn polygraph. And the accuser bears the burden of proof with a current, legitimate evaluation.”

William laughed, too high and too loud. “We have an evaluation,” he said, waving another paper in the air. “Signed this morning by Dr. Schwarz. He’s treated Hannah for years. He can testify to her delusions.”

Robert’s brows lifted. “Dr. Arnold Schwarz?”

“Yes,” William said triumphantly.

Robert’s smile sharpened. “Interesting choice,” he said. “Considering Dr. Schwarz lost his license in Florida for insurance fraud three years ago and currently has three malpractice suits pending in this state. That should make for an enlightening cross-examination.”

He handed a folder to the agent. “In contrast, here is a full forensic psychiatric evaluation of Ms. Vance conducted yesterday afternoon by Dr. Michelle Evans, the state’s chief psychiatrist. Nicholas requested it in advance. Dr. Evans concluded that Hannah is of sound mind, above-average intelligence, and fully capable of managing her estate.”

The agent compared the documents—one a thin affidavit signed that morning by a disgraced doctor, the other a thick report on official letterhead dated twenty-four hours earlier.

I saw the moment his hesitation evaporated.

He handed the guardianship order back to William.

“Sir,” he said, his voice cool now. “Did you obtain this order using a fraudulent medical affidavit?”

William’s smirk faltered. “I…I don’t know anything about that,” he stammered. “My attorney handled it. Dr. Schwarz assured us—”

“That would be perjury,” the agent said. “And obstruction of justice. Turn around. Hands behind your back.”

William’s eyes bulged. “You can’t arrest me,” he yelped. “I am the guardian. I’m trying to protect her.”

“You’re trying to protect your access to stolen funds,” Robert said dryly.

The cuffs clicked shut around William’s wrists, ending his performance.

“You’re not a guardian, William,” I said quietly as they led him past me. “You’re just another pawn.”

—

Six months later, the mildew and stale champagne were gone.

Cliff House smelled like fresh paint, sea air, and something cleaner than either.

Justice.

The hard money loan evaporated the minute the indictment landed. Banks and private lenders don’t like enforcing contracts that require them to defend felonies. The U.S. Attorney’s Office made it very clear that any attempt to collect on that $500,000 would invite a second look at Shoreline Capital’s entire portfolio.

The probate judge didn’t take long either.

Once he saw the chess book will, the forged deed, the indictment, and the competency clause Nicholas had tucked in like a final checkmate, he signed an order that did what my grandfather had wanted all along.

Cliff House, the accounts, the investments.

All of it passed to me.

Legally.

Morally.

Completely.

I didn’t sell.

I could have. Developers still called, waving obscene numbers and promises to “honor the property’s history” with tasteful plaques between their beach condos.

But I kept hearing my grandfather’s voice at the kitchen table: “Money is a tool, Hannah. A house is a tool. The question is what you build with them.”

So instead of cashing out, I started renovating.

The east wing, which had been closed off for years, now echoed with the sounds of contractors instead of arguments. By next spring, the guest suites would be ready to open as the Nicholas E. Vance Sanctuary—a transitional home for women untangling themselves from financial abuse.

Women whose names didn’t show up on deeds or bank accounts.

Women whose families told them they were “too sick” or “too stupid” to manage their own money.

Women who needed a place to stand while they learned how to hold the pen themselves.

On certain evenings, when the wind died down and the ocean turned the color of pewter, I took my tea out onto the balcony that overlooked the water.

I drank Earl Grey from the bone china cup my mother had once kept locked in a glass cabinet, the one she said I wasn’t allowed to touch because “nice things break in your hands.”

It hadn’t broken.

It just belonged to someone else now.

Inside, the library was restored to how it looked before that terrible week—bookcases polished, rug cleaned, my grandfather’s framed degrees rehung.

The desk sat where it always had, facing the window.

The chessboard on top was set up in the middle of a game, just like he used to leave it.

White to move.

There was one difference.

Two black pawns were missing.

People ask where they went. I just smile and say they’ve been removed from play.

My phone buzzed on the desk beside the board.

A notification flashed: COLLECT CALL FROM COUNTY CORRECTIONAL FACILITY.

I didn’t have to check the number to know who it was. Brenda called at least once a week. Sometimes William tried from his own block.

They wanted commissary money.

They wanted to “explain.”

They wanted, more than anything, to rewrite the story.

I no longer felt the urge to argue.

I picked up the phone, stared at the prompt for a second, then tapped DECLINE.

Then I opened my contacts, scrolled to “Mother,” and hit BLOCK.

The same for “William.”

Inheritance, I’d learned, isn’t just property or investments.

It’s the right to decide who has a key to your life.

I walked back to the board and studied the position.

The queen sat quiet in the corner, her line of attack invisible until you looked twice. The rook held an open file. A single white pawn occupied the center, small and stubborn.

Grandpa used to say the loudest player at the table rarely understood the board.

“They mistake noise for power,” he’d murmur, nudging a pawn forward. “But it’s the quiet pieces you watch. They’re the ones setting the trap.”

For most of my life, I’d been the quiet piece.

The girl in the background pouring coffee while other people signed paperwork that shaped my future.

They thought silence meant weakness.

They thought pouring champagne on my grandfather’s book could erase what he’d written.

They forgot one simple thing.

In chess—and in life—you don’t have to flip the board to win.

You just have to let your opponent make the move they can’t take back.

I picked up my white queen and slid her across the board into position.

“Checkmate, Grandpa,” I whispered.

Then I turned back toward the window, where the horizon stretched out gray and endless, and thought about all the people who were still living under roofs owned by their bullies.

If you’ve ever had to outthink someone who lived under your own roof just to keep what was already yours, I hope my story finds you.

And when it does, I hope you remember this:

We’re watching.

We’re learning.

And we’re a lot more patient than they think.

In the months after I blocked their calls, my world shrank down to paint chips, contractor schedules, and spreadsheets.

Grief is loud when you are in it.

Healing is terrifyingly quiet.

I woke up at six most mornings to the sound of gulls and nail guns, pulled on jeans and a hoodie, and walked the skeleton of the east wing with a mug of tea in my hands. The building permit was taped crookedly to the wall near the old servants’ entrance, already curling at the edges from ocean humidity. Where there had once been dusty guest rooms no one used, there were now framed-out suites with wide windows and extra closet space.

“Each room needs a lock on the inside,” I told the foreman the first week. “And a safe. Not the cheap hotel kind. Something bolted, with a real code.”

He had stared at me for a second, then nodded, pencil tucked behind his ear. “You got it, Ms. Vance. Privacy and security.”

He didn’t ask why.

He didn’t need to.

I already knew the women who would come here had their own versions of forged deeds and hollowed-out books. Different details, same pattern. People who loved them using paperwork as weapons.

On an overcast Tuesday in March, I stood in what used to be a storage room for holiday decorations, now studded with fresh electrical outlets and recessed lighting. Lydia, a social worker from a nonprofit in Atlantic County, walked beside me, tablet in hand.

“So intake suite here,” she said, gesturing around. “Private consultation space, lockable file cabinet, panic button under the desk. You sure you want to put your office in the main house and not in town? Once word gets out what this place is, you’ll have visitors.”

“I grew up with people trying to get in here,” I said. “These walls can handle a few more.”

She shot me a look, half curious, half assessing. She knew the broad strokes—local heiress exposes her own family’s fraud, turns mansion into sanctuary—but I’d kept the details close. I wasn’t ready to be reduced to a headline.

We stepped into the hallway. Sun burned through the clouds for a moment, sending a sheet of light across the newly sanded floor.

“First three residents are lined up,” Lydia said, scrolling. “Referrals from legal aid and the hospital social work team. One woman, mid-thirties, husband has her on a ‘budget’ that’s really just him controlling every dollar. One older lady whose son forged her signature on a reverse mortgage. And a nineteen-year-old who just realized all the debt in her name isn’t from college, it’s from her mother opening credit cards with her Social.”

I exhaled slowly.

Different stories.

Same game.

“Have you ever looked at a list of strangers’ problems and seen your own reflection staring back at you?” I asked, more to myself than to Lydia.

She glanced up. “All the time,” she said quietly. “That’s why I do this.”

Her phone buzzed. She excused herself to take the call, leaving me alone in the hallway.

I ran my hand along the wall, feeling the roughness where the old wallpaper had been stripped. When I was little, Brenda used to joke that the house had eyes, that the portraits “saw everything.” She meant it as a warning.

Now, I wanted these walls to witness something else.

Freedom.

—

The first resident arrived on a windy Monday that smelled like rain and salt.

Her name was Kira.

She stepped out of a Lyft in a denim jacket two sizes too big, a rolling suitcase in one hand and a manila envelope clutched flat against her chest with the other. A faded bruise peeked out from beneath the cuff of her sleeve. Her eyes flicked up the front of the house like it might reject her.

“Is this… really okay?” she asked as I opened the door. “I keep thinking someone’s going to pop out and ask for, I don’t know, a VIP pass.”

“This is okay,” I said. “No VIP section. No minimum drink order. Just a very old house trying to be useful.”

She huffed a watery laugh and stepped inside.

Lydia met us in the foyer, already in social worker mode, warm but organized. We brought Kira into the intake room, offered tea, and went through the paperwork.

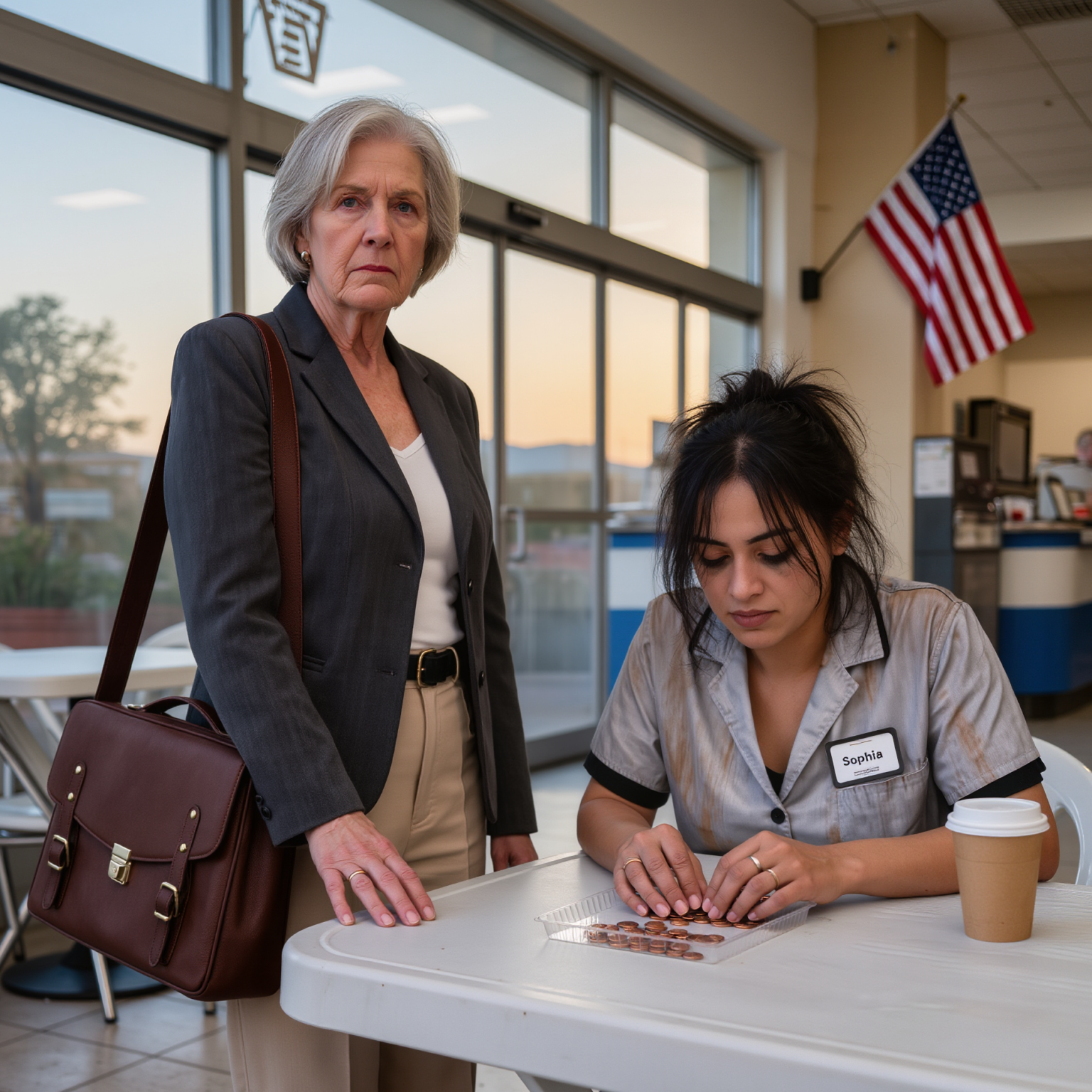

On the table between us, she laid out her life like evidence.

Pay stubs from a diner in Atlantic City.

A lease with only her name on it, even though she paid every bill.

Text messages from a boyfriend who called himself a “provider” but showed up on none of the accounts.

“I thought it was romantic at first,” she said, twisting the strap of her purse. “He said he’d ‘take care of everything’ so I didn’t have to stress. I got to be the ‘soft girl’ for once.” She rolled her eyes at her own words. “Then he started telling me what shifts I could pick up. Who I could talk to. When I could send money back to my mom. And if I pushed back, he’d remind me whose name was on the car. On the Wi-Fi. On the stupid Netflix account.”

She swallowed. “It’s like I woke up and realized my whole life was in his password manager.”

I knew that feeling.

You think you’re being taken care of.

Then you realize you’re being kept.

“What made you leave?” I asked.

She hesitated, then slid one last document across the table.

It was an ER discharge summary from Shore Memorial.

“Last week he ‘joked’ about teaching me a lesson,” she said. “I tripped over his golf bag on the stairs. At least, that’s what I told the nurse. She looked at my eyes for a long time and said, ‘You know, there’s this number you can call if you ever want a different story.’”

Her gaze lifted to mine.

“I took the number,” she said. “And I called. And they said your name.”

My throat tightened.

“They said the girl who turned her own family in built a place for women who were tired of being treated like property,” Kira went on. “Is that… really you?”

I thought about the chessboard in the library, the missing pawns.

“It’s really me,” I said. “And you’re really here. That’s enough for today.”

We showed her to her room—hers, with her own key and a safe bolted into the closet floor. As she walked around, touching the new bedspread, the small desk by the window, the view of the ocean, I saw her shoulders drop a fraction.

Safe doesn’t look like much from the outside.

But if you’ve gone years without it, a lock you control feels like winning the lottery.

She paused at the door before I left.

“Can I ask you something?” she said. “Is your family really in prison?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Does it ever feel… like too much?”

All the time, I almost said.

Instead, I gave her the truth in a smaller piece.

“It feels like exactly enough,” I said. “For what they did. For how long they did it. But it also feels heavy. Like a coat that fits but you wish you didn’t have to wear.”

She nodded like she understood.

“Okay,” she said. “I just wanted to know if justice ever feels… clean.”

“It feels cleaner than the alternative,” I said.

That was the only answer I had.

—

A month later, the east wing was full.

The hallway that used to echo with my brother’s college friends stumbling in drunk now carried softer sounds: laughter from the shared kitchen, low voices from support group nights, the creak of floorboards under slippers instead of stilettos.

We held weekly workshops in the old game room—now painted a calming blue—on topics like “Reading a Lease,” “Understanding Interest Rates,” and “What Happens If You Don’t Cosign That Loan.” Lydia would bring in guest speakers: a pro bono attorney, a credit counselor, a woman from the county DA’s office who specialized in financial exploitation cases.

I listened as much as I taught.

“I used to think ‘being good with money’ meant clipping coupons,” one resident, Maria, said one night, her hands wrapped around a mug of cocoa. “Then my son moved back in and had me sign some papers ‘just to help with his business.’ Now there’s a lien on my house, and I can’t sleep without checking the locks three times.”

“What would you do if the person asking you to sign was your own child?” I asked the group. “Your own parent? Where is your line?”

They were quiet for a moment.

Then the answers came.

“I’d ask to take it to a lawyer, even if they roll their eyes.”

“I’d say, ‘If it’s really such a good deal, you shouldn’t mind me double-checking.’”

“I’d remember what happened to you,” Kira said, nodding at me. “And I’d ask myself if they’re acting like family or like a con artist.”

Every time someone said that—remember what happened to you—I felt a strange mix of pride and nausea.

I hadn’t set out to be an example.

I’d just been tired of being the quiet piece they assumed would never move.

—

Dr. Evans—the psychiatrist who’d evaluated me before the sting—insisted I keep my own therapy going after the dust settled.

“Winning doesn’t erase impact,” she said during one of our sessions, her office smelling faintly of peppermint tea and printer ink. “You’ve been living under chronic stress for years. Your nervous system doesn’t flip off just because a judge signs an order.”

She was right.

Some nights, I still woke up thinking I heard Brenda’s heels clicking down the hall, coming to slam my door open and demand I make coffee for her guests.

Other nights, I dreamed of the FBI raid in stuttering slow motion—Henderson’s laptop chime, the clink of handcuffs, the way the coffee splashed Brenda’s shoes.

“What scares you most now?” Dr. Evans asked once.

“Becoming her,” I said without thinking.

She tilted her head. “Say more.”

I picked at a loose thread on the arm of the couch.

“She ran this house like it was a stage and everyone else was props,” I said. “Now I’m the one signing off on rules, on who lives here, on what they can and can’t do. I keep telling myself I’m different because I’m trying to give power, not keep it. But sometimes when I hear myself say ‘house policy,’ I hear her voice.”

Dr. Evans nodded slowly.

“Control and care can look similar on the surface,” she said. “The difference is whether the other person has a choice. Are you giving these women more choices or fewer?”

“More,” I said.

“Then you’re not becoming her,” she said. “You’re becoming the person Nicholas hoped you’d be when he wrote your name into that will.”

A long silence stretched between us.

“Have you ever realized the person you’re most afraid of turning into is also the reason you’re so careful with your power?” she asked.

I thought of Brenda in handcuffs, sputtering about her title, her house, her reputation.

“I think that fear might be the only good thing she ever gave me,” I said.

—

On the six-month anniversary of the raid, the local paper ran a follow-up piece.

FRAUD CASE LEADS TO NEW LIFE FOR VICTIMS OF FINANCIAL ABUSE, the headline read.

The article had a photo of me on the balcony, hair blown back by the wind, the house rising behind me like something out of a postcard. You could almost see the small plaque we’d had installed by the front gate: NICHOLAS E. VANCE SANCTUARY.

The reporter called me “soft-spoken but unflinching.”

Brenda would have hated that.

She always preferred loud and performative.

I clipped the article and tucked it into the back of the chess book.

Grandpa would have liked that part.

That afternoon, as I was sorting through a donation of gently used coats in the foyer, the doorbell chimed.

I wasn’t expecting any new residents.

When I opened the door, David Patel—the bank officer who had first said the words “call fraud”—stood on the porch, hands jammed into the pockets of his windbreaker.

“Mr. Patel,” I said, surprised. “Did I miss a loan payment?”

He laughed. “Not unless you secretly took out a second mortgage with someone shadier than me,” he said. “May I?”

I stepped aside to let him in.

“I was in the area visiting a client,” he said, glancing around the foyer. “Thought I’d see if the place from the incident report actually existed or if I’d imagined the whole thing.”

“It exists,” I said. “And so do the consequences.”

He nodded, sobering.

“I wanted to say thank you,” he said. “Clients lie to us all the time. Some days it feels like our whole job is deciding which lie is least expensive. You came in with that book and looked me straight in the eye. If I’d brushed you off—if I’d approved that line without reading too closely—you’d still be living under the same roof as people who stole from you.”

“You followed the rules,” I said. “That’s literally your job description.”

He smiled crookedly. “You’d be surprised how many people get promoted for looking the other way,” he said. “You reminded me why I went into this in the first place.”

We walked through the house together. I showed him the wing under renovation, the intake room, the group space. He listened more than he talked.

At the library door, he paused, looking at the chessboard.

“Looks different when it’s not covered in loan docs,” he said.

“Feels different,” I said.

He gestured toward the missing pawns. “What happened to those?”

“Let’s just say they’re somewhere they can’t hurt anyone anymore,” I said.

He didn’t push.

On his way out, he hesitated.

“I have a sister in Edison,” he said. “Her husband is… not as bad as what you dealt with. But he ‘handles the finances’ in a way that makes me nervous. He laughs when I suggest she keep a separate account. Says I’m trying to ‘undermine the family.’” He looked at me. “What would you tell her?”

I thought of all the women sleeping a little easier under my roof.

“I’d tell her that any man who’s scared of his wife knowing how money moves is already undermining the family,” I said. “And I’d tell her she deserves an account with her own name on it and nobody else’s password.”

He exhaled like he’d been holding his breath since he knocked.

“Yeah,” he said. “That’s what I thought.”

Sometimes, the ripple reached farther than I could see.

—

On a rainy Thursday, a letter arrived from the county correctional facility.

Not a call this time.

Paper.

I recognized Brenda’s handwriting instantly—big, swooping loops that always made her signature look like a logo.

For a long time, I stood in the kitchen just holding the envelope, the way I’d once held the chess book, unsure whether opening it would ruin or save anything.

Finally, I slid a knife under the flap.

The letter was three pages long.

The first was all performance.

You’ve always misunderstood me, Hannah. I did the best I could with what I had. Your grandfather pitted us against each other. You humiliated me in front of the entire county.

Somewhere on page two, the tone shifted.

Prison uniforms, it turned out, stripped away some of the armor.

They cut my hair, she wrote. Do you know what it feels like to have someone else decide how long your hair is allowed to be? To tell you when you can shower, when you can eat, when you can make a phone call? To stand in line and wait for your name like you’re checking out at a grocery store and you’re the item?

Yes.

I knew.

I’d lived a version of that under her roof.

She just didn’t see it as a cage when she was holding the key.

On the last page, her words got smaller.

Your grandfather used to tell me I played too loud, she wrote. That I confused making a scene with making a move. Maybe he was right. Maybe I only ever learned how to flip the board, not how to play the game. I don’t know how to apologize for what I did to you without sounding like I’m asking for something.

She underlined the next sentence twice.

I am not asking you for anything.

I read that line three times.

I waited for the ask that always came.

It didn’t.

Instead, at the very bottom, so faint I almost missed it, she’d written:

If there is a version of the future where you can think of me without hating me, I hope you get to live in it. Even if I don’t.

I folded the letter carefully and slid it into the back of the chess book, behind the newspaper clipping.

I didn’t know if that was forgiveness.

But it felt like filing a piece away instead of letting it sit on the counter staining everything.

Have you ever received an apology that didn’t fix anything but still moved something loose inside you?

It didn’t change the facts.

It didn’t unlock any doors.

It just softened one corner of a very hard day.

—

The night we welcomed our tenth resident, we held a small ceremony in the dining room.

No candles.

No speeches.

Just a long table, mismatched plates, and a stack of index cards with questions like:

What’s one money decision you’re proud of?

When did you first realize “family” and “control” aren’t the same thing?

Where do you want to be one year from now that has nothing to do with anybody else’s name on a piece of paper?

We went around the table answering.

When it was my turn, I flipped my card over.

“What’s one boundary you’re glad you finally set?” it read.

I thought of the blocked phone calls.

The empty contact slots where “Mother” and “William” used to be.

“I’m glad I decided my front door is not a revolving door,” I said. “That the fact someone shares my DNA doesn’t give them automatic access to my peace.”

Kira raised her glass of sparkling cider.

“To locked doors and open futures,” she said.

Glasses clinked.

The house, for the first time in years, felt full in a way that wasn’t suffocating.

—

Sometimes I still stand in the library late at night, the only light coming from the lamp on the desk.

The ocean is a dark mass beyond the window. The rest of the house is quiet—no muffled arguments from down the hall, no clink of crystal as someone pours another drink, no hurried footsteps as staff scramble to make everything look effortless.

Just the clock ticking and my own breath.

Which moment would have hit you hardest if you’d been walking beside me through all of this?

The slam of a champagne-soaked book into a trash can at my grandfather’s funeral.

The look on the loan officer’s face when he realized the collateral was stolen.

The click of handcuffs closing around the wrists of the people who raised me.

Or the soft, almost invisible moment when I slid a letter into the back of a chess book and chose not to let it run my life.

For me, they all land differently on different days.

Some mornings, the memory of the raid steadies me when I’m tempted to second-guess myself.

Other days, it’s the quieter scenes that stay—the way Kira smiled the first time she realized her paycheck was hitting an account he couldn’t touch, or the way Maria sat a little taller after calling the bank to put a fraud alert on her credit.

You don’t always feel the exact second you stop being someone’s pawn.

Sometimes you only realize it later, when you look back and see the line you finally refused to cross.

Ranh giới.

Boundary.

Whatever language you put it in, it’s the first brick in the wall between you and the people who thought your life was theirs to arrange.

If you’re reading this on a tiny screen, maybe on a break at work or hiding in your car in a grocery store parking lot, I’m curious.

What was the first boundary you ever set with your own family that actually stuck?

Was it the first time you said no to a “small favor” that was anything but small?

Was it the day you decided not to co-sign something you didn’t understand?

Was it when you stopped picking up a certain kind of phone call?

Or was it quieter, like deleting a number and choosing your own peace for once?

If you feel like sharing, I’ll be here, somewhere between the kitchen and the library, making sure the locks work the way they’re supposed to and the pawns on the board stay exactly where they belong.

We spent a lot of years learning how to survive under someone else’s rules.

Now we’re learning how to write our own.

And trust me on this part.

Once you see the board clearly, you never go back to pretending the game isn’t rigged.