My daughter raised her glass and said, “Some mothers just ‘take up space.’” My whole family laughed. I smiled and replied, “Good thing I just finished my own home 3,000 miles away. Don’t worry—after tonight, you won’t have to see me ‘take up space’ anymore.”

The night my daughter made the toast, the air inside her dining room felt too polished to breathe. Lydia’s new house, tucked into an upscale subdivision on the edge of Charlottesville, Virginia, gleamed like the pages of a design magazine—white walls, narrow candles, a table long enough for twelve. The hardwood floors shone like still water under recessed lights, and the faint smell of rosemary chicken drifted in from her gleaming open-concept kitchen.

Outside, the Blue Ridge Mountains were only a dark suggestion against the winter sky, and the driveway was crowded with late-model SUVs and silent electric cars plugging into sleek chargers. Inside, everything was curated: the art on the walls, the music humming softly from hidden speakers, even the way people laughed.

Every detail of that house announced her success. The Restoration Hardware light fixtures, the framed diplomas from UVA and Wharton, the wine fridge humming softly in the corner stocked with bottles from Napa and Willamette. Every guest seemed to echo it back as they talked—about business trips and vineyards, ski cabins in Colorado, internships in New York, mergers and promotions.

The clink of forks, the murmur of wine being poured, the rise and fall of polished laughter all blurred together into a kind of expensive static.

I sat near the end of the table, in a chair that felt slightly shorter than the rest, half listening as her colleagues compared flights and frequent flyer miles, Napa tastings and Napa prices, which TSA PreCheck line moved faster, which airline lounge had the better sparkling water.

I was proud of her, of course. That pride had been the spine of my life for thirty years. But pride is a quiet thing, and the room was very loud.

Someone asked Lydia about the art piece hanging over the sideboard—three white canvases in a row with faint gray streaks.

“It’s by a Brooklyn artist,” she said lightly. “My mom paints too, but more…traditional stuff.”

The woman next to her smiled politely, already turning back to her glass.

I pressed my napkin flat against my lap, as if I could iron out the crackle in my chest.

Then Lydia stood.

The stem of her glass caught the light, scattering it across the table and over the faces turned toward her. She wore a black sleeveless dress that made her look like she belonged on the cover of an alumni magazine, the kind the university mailed out twice a year with stories about donors and success.

She smiled at the room.

“I just want to thank everyone for being here,” she said. “It means a lot to celebrate with people who make space for one another.”

The room hummed with approval, a soft chorus of mm-hmms and clinking glass, the kind of synchronized response you hear at conferences and cocktail hours.

Then she turned to me, her tone soft but sharp enough to cut.

“Some mothers,” she said, her voice smooth, “just take up space.”

The words slid out too easily, a little too rehearsed, like a joke she’d tried out on someone else first and liked the sound of.

It was said like a joke. Just a little too smooth. Just a little too sharp.

The laughter came instantly—bright, practiced, a burst of sound that felt like a flashbulb going off. A few guests hid their smiles behind napkins. Someone poured more wine, the glug-glug into crystal suddenly very loud in my ears.

I felt the sound pass through me like wind slipping through a cracked window in an old Virginia farmhouse, that thin whistle that means the frame doesn’t quite fit anymore.

I could have said nothing. That was the old pattern. Let it go. Pretend not to notice. Swallow the sting and call it love.

But something inside me—something that had been quiet for far too long—refused.

I set my glass down gently. The stem made a small, clear sound against the table, like a bell only I could hear.

“Good thing,” I said, my voice steady, “I just built my own house three thousand miles away, across state lines where no one expects me.”

The laughter faltered. The room seemed to inhale and forget how to exhale. One of her friends coughed. The silence that followed was strange, heavy, electric, like the pause when a summer storm is about to break and the air smells faintly of metal.

Lydia blinked, unsure if I was joking.

I smiled, not wide, just enough to meet her eyes and let her see that, for once, I was not backing away.

No one spoke after that. Conversation eventually crawled back, but the rhythm had changed. Topics stumbled. Jokes landed with less certainty. Even the candles seemed to flicker differently, their thin flames bending toward some draft only I could feel.

When dessert arrived—tiny lemon tarts on stoneware plates, garnished with edible flowers someone must have driven across town to find—I excused myself with a polite smile.

“Long drive,” I said. “Early morning.”

Lydia offered a tight nod without meeting my gaze. Someone called after me, something about drive safe, but it barely grazed my ears.

I stepped out into the cold Charlottesville night. The street lamps cast long shadows across the manicured sidewalks. The air was sharp enough to sting, smelling faintly of wood smoke, damp pavement, and someone’s dryer sheet drifting from an open vent.

Her subdivision was quiet, the kind of silence you get when garages close automatically and neighbors wave only from car windows.

On the drive home, the city lights blurred into streaks of gold in my windshield. I passed the familiar big-box stores—Target glowing red in the distance, Lowe’s sign buzzing faintly, the twenty-four-hour Kroger with its near-empty parking lot and a lone cart pushed crookedly against a median. I drove past brick faculty houses near the university, their porches lit with warm lamps and stacked with Amazon boxes and university mail.

Years ago, Richard and I had gone to dinner parties in those houses, back when I still believed that belonging was something you could earn if you were useful enough. If you brought the right side dish. If you laughed at the right jokes.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t even feel angry.

I just felt done.

Done being the quiet outline at someone else’s table. Done smiling at jokes that sharpened themselves on my ribs. Done being grateful for a chair I was supposed to shrink inside.

By the time I turned onto my street, past the cracked sidewalk where Lydia once learned to ride a bike, I already knew this moment was not an ending.

It was the start of something I had owed myself for years.

The next morning, I woke before dawn. A pale gray light leaked in around the edges of the blinds. The house was silent except for the faint hum of the old refrigerator and the occasional rush of a car on the nearby bypass. In the distance, a train horn sounded, long and low.

I sat at the kitchen table—the same honey-colored oak table Richard and I had bought from Sears in our first year of marriage. We’d driven to the mall in his rusted Toyota, argued about whether to get the round one or the rectangle, and eaten cinnamon pretzels in the food court to celebrate the purchase. The varnish had worn thin where his elbow used to rest.

Sometimes I could still hear his voice there—steady, practical, shaped by years of faculty meetings and lectures at the university.

“You’re the anchor, Iris,” he’d tell me, his hand covering mine. “I couldn’t do this without you.”

He meant it, I think. But being someone’s anchor means you never move.

When Lydia was born, Richard’s work at the university became our family’s orbit. Faculty dinners in old brick houses near the Rotunda, late nights with blue exam booklets spread across the dining room table, conferences that took him to cities I’d only seen on maps. I stayed home, painted between chores, and told myself the art could wait.

Once, when Lydia was ten, I showed her a portrait I’d finished—a woman in a red scarf, looking out a rain-streaked window, the light catching her jaw.

“You should paint something people would actually hang in their houses,” she said, squinting, her voice as careless as tossed paper.

I laughed back then.

It didn’t sting yet. Or I told myself it didn’t.

After Richard’s heart attack, the world split cleanly in two: before and after. The “after” was quiet and echoing. I filled the silence with usefulness. I taught part-time at the middle school, correcting essays in red pen while kids slammed lockers down the hall. I volunteered at the library, shelving books and recommending novels I’d loved in college. I cooked for Lydia when she came home from college, filling the fridge as if food could anchor her where love could not.

Every visit felt shorter than the last.

“You don’t have to fuss, Mom,” she’d say, pushing my hand away as I set down her plate.

“I already ate with friends.”

“I just wanted you to have something warm,” I’d tell her, straightening the silverware, smoothing the tablecloth that no one noticed.

“It’s fine. You should relax more.”

Relax.

The word always sounded like permission I hadn’t earned, like a luxury brand meant for someone else.

When Lydia got her first job in Richmond, I helped her move into a walk-up near Carytown. The building smelled like old paint and someone’s burnt toast. We spent a whole weekend packing boxes. She organized everything by color—books arranged from white spines to black, sweaters folded into muted rainbows, coffee mugs lined up by shade.

I kept asking where she wanted the small things: photos, keepsakes, the clay bird she’d made at eight in a YMCA summer arts program, its beak chipped, its wings uneven.

“Just toss them,” she said, distracted, taping a box. “I’m trying to start fresh.”

“Are you sure?” I asked, my fingers tracing the clay bird’s uneven side.

She didn’t look up.

“Yeah, it’s fine. I don’t need that stuff.”

So I did.

One by one, the small pieces went into a trash bag that crinkled too loudly in the quiet apartment.

That night, while she slept on the couch surrounded by disassembled IKEA and half-drunk LaCroix cans, I sat in the dark living room, turning her old school photo over in my hand. Third grade. Gap-toothed smile. Hair in two uneven braids. Her smile had always been tilted toward the light.

Away from me.

Back in Charlottesville, my house still smelled faintly of turpentine and damp leaves, like every season layered on top of the last. A forgotten still life on the dining room sideboard collected dust. A jar of brushes sat in cloudy water beside the sink.

I walked from room to room, tracing the outlines of old frames, the spaces where our lives used to fit together. The couch Richard had napped on. The hallway where Lydia had measured her height in pencil marks. The doorframe where the marks now faded like old promises.

I realized I had spent years keeping the rooms warm for someone who rarely looked back inside.

That night, I turned off the television halfway through the evening news. The anchor’s voice cut off mid-sentence. The house was too quiet, the kind of silence that made every thought louder.

My reflection stared back at me from the dark screen—a woman with paint on her hands and nothing of her own pinned to the walls.

I pulled Richard’s old ledger from the drawer, the one he used for our household expenses, and set it on the table. The pages were yellowed at the edges, the lines faint but straight. It still smelled faintly of pencil lead and coffee and the ghosts of long-ago arguments about car repairs and tuition.

I drew two columns.

On the left, I wrote: Staying.

On the right, I wrote: Leaving.

For a long time, the pencil didn’t move. The clock over the stove ticked louder. A car’s headlights slid briefly across the ceiling and disappeared.

Then I began adding numbers I knew by heart: my small pension from the school district, the savings account I had guarded for years, the insurance payout after Richard’s death that I’d barely touched. Not wealth, but enough.

I added up the cost of property taxes, repairs on a roof that always leaked in March, groceries for one person in a house built for three, the endless cycle of keeping up a lawn I no longer enjoyed, a driveway no one pulled into.

Then I wrote one more line, though it didn’t fit neatly on either side.

Dignity.

I didn’t assign it a number.

The phone rang.

It was Lydia.

Her voice was light—too light, the way people sound when they’re calling to smooth something over but don’t quite believe they did anything wrong.

“Mom, about last night,” she said. “I was just joking. You know that, right?”

“I know what you meant,” I said softly.

“I just think you’re taking things too seriously. People laugh at family dinners. That’s what they do.”

“They laughed at me,” I said. “Not with me.”

She sighed—the sound of someone adjusting a conversation to their own comfort.

“You’re being dramatic,” she said. “You should focus on your art again. Maybe that’ll make you feel better.”

“It might,” I said. “It also might make me leave.”

“What does that mean?” she asked, her voice sharpening, that familiar edge sliding back in.

“Nothing you need to worry about tonight.”

I hung up before her tone could turn cutting.

Back at the table, I filled in the final figures. The cost of staying was predictable. The cost of leaving was uncertain, but uncertainty, for the first time, felt lighter than the weight of being tolerated.

I closed the ledger and rested my hand on the cover.

It wasn’t rebellion. Not yet.

Just arithmetic.

Outside, the streetlight flickered across the window—steady, patient, waiting.

I realized I had already made the choice.

The numbers had only confirmed it.

The next few nights, sleep refused me. I stayed at the kitchen table with my laptop open, its pale light washing over the ledger I’d left out. The router blinked in the corner, the only other pulse in the house.

I typed: homes for sale near the coast.

Pages of glossy photographs appeared. Porches slick with rain. Wide skies over narrow streets. Coffee shops with chipped mugs and crowded bulletin boards. Small houses with peeling paint and flower boxes. Big windows that let in more than light.

For reasons I couldn’t fully name, I kept circling back to Oregon. The map on the screen looked like a promise.

The names of the towns sounded soft in my mouth.

Ashland. Corvallis. Portland.

Photos of Portland glowed on the screen: bridges arching over gray water, food trucks huddled under strings of lights, bookstores big enough to get lost in, people walking in good raincoats and bad sneakers, their shoulders relaxed despite the drizzle.

Portland felt alive in a way I hadn’t in years.

It wasn’t the ocean that called me.

It was the feeling of distance—the kind that let you breathe.

The next morning, I dialed the number on one of the listings. My hand shook only a little.

A woman answered, her tone bright but grounded.

“Hawthorne Realty, this is Mara.”

“Hello, I’m calling from Virginia,” I said. “I’m looking for something small. Maybe two bedrooms. Something with light.”

“Light we have plenty of,” she laughed. “And rain to balance it out.”

Her warmth steadied me, like a hand on my back.

We talked for nearly an hour—mortgages and closing costs, property taxes and neighborhood gossip. She told me which blocks had good trees and bad parking, which parts of the city were changing too fast, which ones still had corner diners that served pancakes all day.

She never once asked if I was married or if anyone would be joining me.

That small omission felt like kindness.

After we hung up, I stared at the notepad where I’d written her name. MARA, all caps, underlined twice.

For the first time in months, my hand wasn’t shaking.

By the end of the week, I had a plan.

I called a real estate agent in Charlottesville to list the house. When he asked for a reason, I said, “It’s time for someone else to make memories here.”

He laughed politely and didn’t ask more questions.

The paperwork came quickly: signatures, forms, polite emails full of words like transfer and settlement and closing date. I downloaded, printed, signed, scanned. The small rituals of leaving.

I packed quietly, one room at a time. Lydia didn’t notice. Our calls had grown shorter since the night of her toast. We talked about the weather, about her job, about anything but that.

Three weeks later, she finally did notice.

“You sold the house?” she said, her voice rising. “Without telling me?”

“I didn’t think you’d be interested,” I said. “You’re busy.”

“That’s not the point,” she snapped. “Where will you even go?”

“West,” I told her. “Somewhere with light and rain in equal measure.”

There was a long silence before she muttered, “You sound ridiculous.”

“Maybe,” I said, smiling to myself. “But maybe I sound free.”

I ended the call, opened the онлайн map again, and placed my finger on Portland.

The distance didn’t scare me anymore.

It felt like air.

By the time the realtor’s sign went up in the front yard, the house had already started to look like a stranger’s. Shelves emptied. Echoes where laughter used to be. Dust outlines where pictures had hung for decades.

I stood in the hallway holding a box labeled KEEP, another labeled DONATE, and a trash bag for what neither memory nor mercy could justify.

Joanne came over after work, sleeves rolled up, hair pinned back the same way she wore it when we used to teach together at the middle school.

She looked around the living room and sighed.

“You sure about this, Iris?” she asked. “You’ve lived here most of your life.”

“I’m sure,” I said, though my throat caught halfway through.

We started with the easy things—old coats, mismatched mugs, broken picture frames. But every drawer had a voice. Every junk box held some version of who I had been.

The first box of china stopped me cold. White porcelain with blue edges. Wedding gifts from a life that had ended quietly in a hospital room, fluorescent lights buzzing overhead.

Lydia once said, “They look too fragile. Just like you.”

I set one plate aside—the least chipped—and wrapped the rest in newspaper.

Joanne lifted a framed photograph from the mantle—Richard in his university jacket, Lydia perched on his shoulders at a fall football game, a blur of orange and navy behind them, a foam finger in her small hand.

“You keeping this?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “But not to hang. I just want to remember who we were before we forgot.”

She nodded, eyes soft.

“Then it goes in KEEP.”

We worked in silence for a while, dust turning to gray clouds in the sunlight slanting through the front windows. The floor creaked in all the familiar places. I found my old paint-stained stool from the art room—legs uneven but still sturdy. My name was scratched into the underside in faint blue ink, IRIS C.

I brushed my fingers across it.

“This one’s coming with me,” I said. “It’s seen more of me than anyone else has.”

By sunset, boxes were stacked to the ceiling—small cardboard monuments to a life carefully folded away. Joanne poured two glasses of grocery-store wine and joined me on the porch. The air smelled of cut grass and someone’s charcoal grill down the block. A dog barked two streets over.

“You’re really doing it,” she said, handing me a glass. “You’re brave, Iris.”

I smiled, the kind that trembles but holds.

“No,” I said. “I’m just tired of staying where I disappear.”

The cicadas hummed low in the trees. I took my journal from the table and wrote a single line:

I am not leaving home. I’m taking myself with me.

When Joanne left, I stayed there until the sky turned violet, the porch light casting a small circle on the steps. Surrounded by boxes that no longer felt heavy, I let the quiet settle over me like a new kind of blanket.

The plane landed in Portland under a gray sky that looked almost kind.

From the airplane window, the city below was a patchwork of rivers, bridges, and dark green patches of fir trees. The plane taxied past other jets streaked with rain, ground crew in bright vests moving like figures in a small, careful play.

By afternoon, after a cab ride past food carts and graffiti-bright walls, we turned down a tree-lined street in Southeast. Bungalows and old foursquares sagged or shone depending on who had loved them last. Bikes leaned against porches. Wind chimes tinkled in the damp breeze.

I stood in front of the small bungalow on Hawthorne Street, a set of keys in my hand and the smell of rain and coffee in the air.

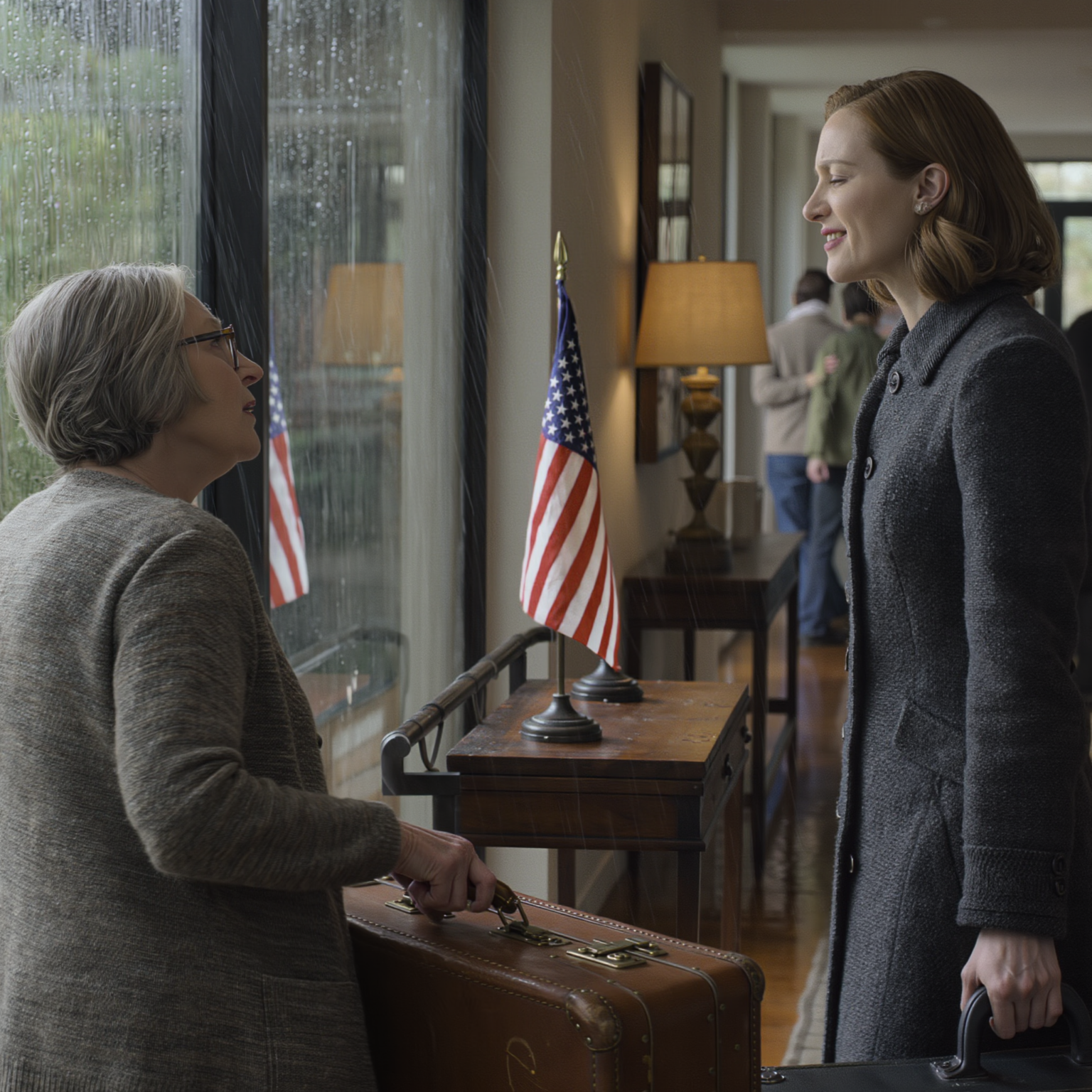

The realtor, Mara Singh, smiled as she passed me an envelope with the final paperwork.

“It’s a good house,” she said. “Quiet. Morning light comes right through those front windows. You’re walking distance from good coffee and a decent bookstore, and the bus stop’s on the corner if you ever feel adventurous.”

“I could use some light,” I told her. “Coffee and bookstores won’t hurt either.”

She grinned.

“Welcome to Portland, Iris.” Then she drove off, wipers squeaking against the windshield.

I walked up the short path, my shoes damp from the wet sidewalk, and unlocked the door.

The floors creaked softly as if the house was waking up with me. The air smelled of cedar and fresh paint. Boxes waited by the wall, labeled in my handwriting: PAINT SUPPLIES, BOOKS, KITCHEN THINGS, and a few marked simply GHOSTS.

Memories. Forgotten echoes.

I didn’t bother unpacking right away. I sat on the floor with a sandwich from the airport, the bread already a little stale, and listened to the rain hitting the porch roof in a steady, forgiving rhythm.

The silence wasn’t heavy.

It felt like space I could finally fill with my own breath.

The next morning, I opened every window and let the air move through. The cedar smell was sharp, clean, almost sweet. Somewhere nearby, someone was grinding coffee beans; the sound carried faintly on the damp air.

I painted one wall in the front room a deep sea green, the same color I’d used for the backdrop of my first classroom mural. The brushstrokes steadied me. Each line felt like a sentence in a language I was relearning, a language that had nothing to do with being useful.

A neighbor, a woman with gray curls, gardening gloves, and a faded University of Oregon sweatshirt, stopped by the fence.

“You just move in?” she asked.

“Yesterday,” I said, lowering my paintbrush.

“Well, welcome to the neighborhood,” she said. “Lavender does well here. Keeps the rain from smelling like rain.”

“I didn’t know rain could smell like anything else,” I said.

She laughed.

“Oh, you’ll see. Around here it smells like wet dogs and car exhaust unless you fight back. I’m Eileen, by the way. Across the street—the yellow house with too many wind chimes.”

“Iris,” I said. “Nice to meet you, Eileen.”

That afternoon, I walked down to the local nursery on Division, bought three small lavender bushes and a bag of potting soil, and planted them by the steps. The dirt clung to my palms, cold and grounding. My knees ached when I stood up, but it felt like the good kind of ache.

Inside, the furniture was sparse—a bed, two chairs, a folding table I’d ordered online. The rooms echoed when I walked through them. But at night, when I turned on the single lamp beside the window, the room glowed like a promise kept. Outside, car headlights passed in slow smears of light. Somewhere down the block, someone played a guitar on a porch, off-key but earnest.

I stood there for a long time, the lamp’s glow soft against the rain-streaked glass.

I wasn’t waiting for anyone.

I just wanted the house to know I was here.

Finally owning my own presence.

The first time I met Tomas, he was hauling a bundle of salvaged oak boards into the back of his pickup truck parked in front of my house. His forearms were streaked with sawdust, his flannel shirt rolled to the elbows, his dark hair pulled back with a rubber band that looked like it had once belonged to a bunch of asparagus.

He caught me watching from the porch, mug of coffee in my hands.

“You need wood for anything?” he asked, grinning. “Looks like you’ve got a porch that could use a table.”

“I was thinking about one,” I said. “A long one. For company I don’t have yet.”

He laughed, not unkindly.

“That’s the best reason to build it,” he said.

Two days later, he showed up with a toolbox and the boards.

“Payment’s a cup of coffee,” he said, kicking off his boots at the steps. “Maybe a sandwich if I pretend to look hungry.”

“I can manage both,” I said.

I brewed a pot—strong and a little burnt, the way Richard used to like it—and we worked in the yard. Tomas measured twice and cut once, his hands moving like music: sure, patient, quiet. The sharp scent of sawdust mixed with the damp smell of the yard.

Eileen wandered over mid-afternoon with a plate of lemon bars, plastic wrap stretched tight over the top.

“You’re finally letting someone help you,” she teased, setting the plate on the railing. “About time.”

“I guess I am,” I said.

“He makes good tables,” she said. “Terrible coffee, though. Good thing you’ve got that covered.”

We built the table over three days. Tomas refused to cut it short, even when I suggested making it smaller.

“A table like this,” he said, running his hand along the grain, “should make room for whoever shows up. No one sits at the edge of their own life.”

By the end of the week, it stretched nearly ten feet, sanded smooth, the color of warm honey. It smelled faintly of rain and possibility. I found ten identical chairs at a thrift shop, each one creaking in its own rhythm when I tested them in the aisle.

No head. No foot.

Just a line of equals.

That Sunday, I cooked soup and baked bread, the house filling with the smell of garlic and yeast. Eileen brought wine—a bold red she claimed was too nice for the likes of us. Tomas arrived with candles in mismatched holders, one of them shaped like a small ceramic chicken.

When we sat down, laughter came easily. No one interrupted. No one tried to fill every silence. Stories unfolded without competition: Tomas talking about rebuilding porches across the city, Eileen describing her former life as a nurse, me telling them about my students in Virginia who had once painted a mural of outer space and accidentally given Saturn three rings.

I looked around at their faces—neighbors, not family—and yet the room felt full in a way it hadn’t in years.

For the first time, I didn’t need to earn my seat.

It was already waiting for me.

The article came out on a Thursday morning.

Eileen brought the newspaper over, grinning like she’d won a prize.

“Look,” she said, tapping the front page of the community section with a flour-dusted finger. “The woman who built a table for strangers.”

There I was in the photograph—hands dusted with flour, laughing beside Tomas and Eileen, ten mismatched plates spread across the oak table, candles burning at different heights. The headline was kind. The photo felt honest.

By afternoon, the phone started ringing. Neighbors calling to say they’d seen the article. An old colleague from Charlottesville who’d seen the story shared on Facebook. Even a student I hadn’t seen in years who’d moved to Seattle and stumbled across the link.

They all said the same thing.

“You look happy.”

When the phone rang again that night, I almost didn’t answer. But the silence on the line before the first word told me who it was.

“Mom,” Lydia said. Her voice was clipped, tight. “You’re in the paper. And online. Everyone’s sending me pictures.”

“I see,” I said.

“You’re embarrassing me,” she continued. “People think I drove you away. They think I was cruel.”

“I didn’t say that,” I said quietly.

“You didn’t have to,” she snapped. “The story makes it look like I abandoned you.”

“You didn’t drive me, Lydia,” I said, letting the pause linger. “I walked.”

She exhaled sharply, the sound harsh in my ear.

“You always twist things,” she said. “I was trying to make you part of my life, but you—” she broke off. “You just left.”

“I left the table,” I said. “Not the love. The table wasn’t big enough for both of us.”

She laughed once—hollow.

“You sound dramatic,” she said.

“Maybe,” I answered. “But this time, I sound like myself.”

For a long moment, neither of us spoke. Rain tapped against the window. Somewhere outside, a car door slammed.

Then the line went dead.

I placed the phone on the counter and turned toward the window. Outside, the porch light glowed over the lavender—steady and soft. The table waited in the next room, still warm from the night before.

The call came three days later, just after dusk. I almost let it ring out, but something in me—maybe habit, maybe mercy—made me pick up.

“Mom,” Lydia said, her voice tight. “Aunt Carol called. She saw the article. Everyone’s talking about it. Do you realize what that sounds like?”

“It sounds like what happened,” I said evenly.

“That’s not fair,” she snapped. “I gave you everything. I helped after Dad died. I called. I visited.”

“You visited when it was convenient,” I said quietly. “And you called when there was silence to fill.”

She fell silent for a moment, the air thick between us like humidity before a storm.

Then, more softly, “Why do you have to make it sound like I’m the villain?”

“Because I never told the truth before,” I said. “I raised you to stand tall, Lydia—not to stand on me.”

The line went still. I heard her breathing, uneven, small, like a child who’d run too fast.

“I didn’t mean to,” she whispered finally.

But the apology came out unfinished, barely formed, the outline of a word instead of its full shape.

“I know,” I said. “You thought I’d always be there, holding you up.”

Her voice cracked—a tiny sound, like something breaking open.

“I’m sorry,” she managed.

The word hung between us, trembling.

The call ended softly. Not with anger, but with a quiet that felt almost merciful.

Weeks passed, and the rain returned, soft and steady against the windows. Moss brightened on the sidewalk. The lavender by the steps deepened to a richer green.

That evening, I set the table for dinner—soup simmering on the stove, bread warm from the oven, wine breathing beside the candles. Tomas and Eileen were due any minute. The porch light was already on, a habit now.

It wasn’t a beacon.

It was a promise to myself that I’d never live in the dark again.

As I adjusted the napkins, my phone buzzed on the counter. The screen lit with a name I hadn’t seen in weeks.

Lydia.

Her message was short.

Mom, can I visit?

I stood for a moment, the phone warm in my hand, the kitchen filled with the smell of garlic and rosemary and fresh bread.

Old reflexes stirred—the urge to say yes immediately, to offer up my time, my bed, my peace, without condition.

I took a breath instead.

Then I typed slowly, carefully.

There’s a seat for you if you come as yourself.

I hit send and placed the phone face down.

Tomas knocked first, holding a jar of olives and a smile.

“Full house tonight?” he asked, stepping inside and shaking the rain from his hair.

“Maybe one more,” I said.

Eileen followed, her laughter already filling the kitchen as she hung her raincoat by the door.

“Smells amazing,” she said. “If you ever get tired of painting, you could run a little supper club and charge ridiculous prices.”

“I think I like charging nothing,” I said. “It keeps the right kind of people at the table.”

We poured wine, passed bread, and let the conversation find its rhythm. Outside, the rain softened to a mist, the porch light haloed in gold. A bus hissed to a stop at the corner, then pulled away, leaving the street quieter than before.

When the meal began, I added one more plate at the end of the table. Not out of hope, but out of peace.

I didn’t check the door again.

I didn’t need to.

The light was enough.