My nephew mouthed, “Trash belongs outside,” the whole family laughed; I just took my son’s hand and left — that night Mom texted “monthly transfer?”; the next morning, an ice-cold email knocked and Sunday dinner was no longer the same…

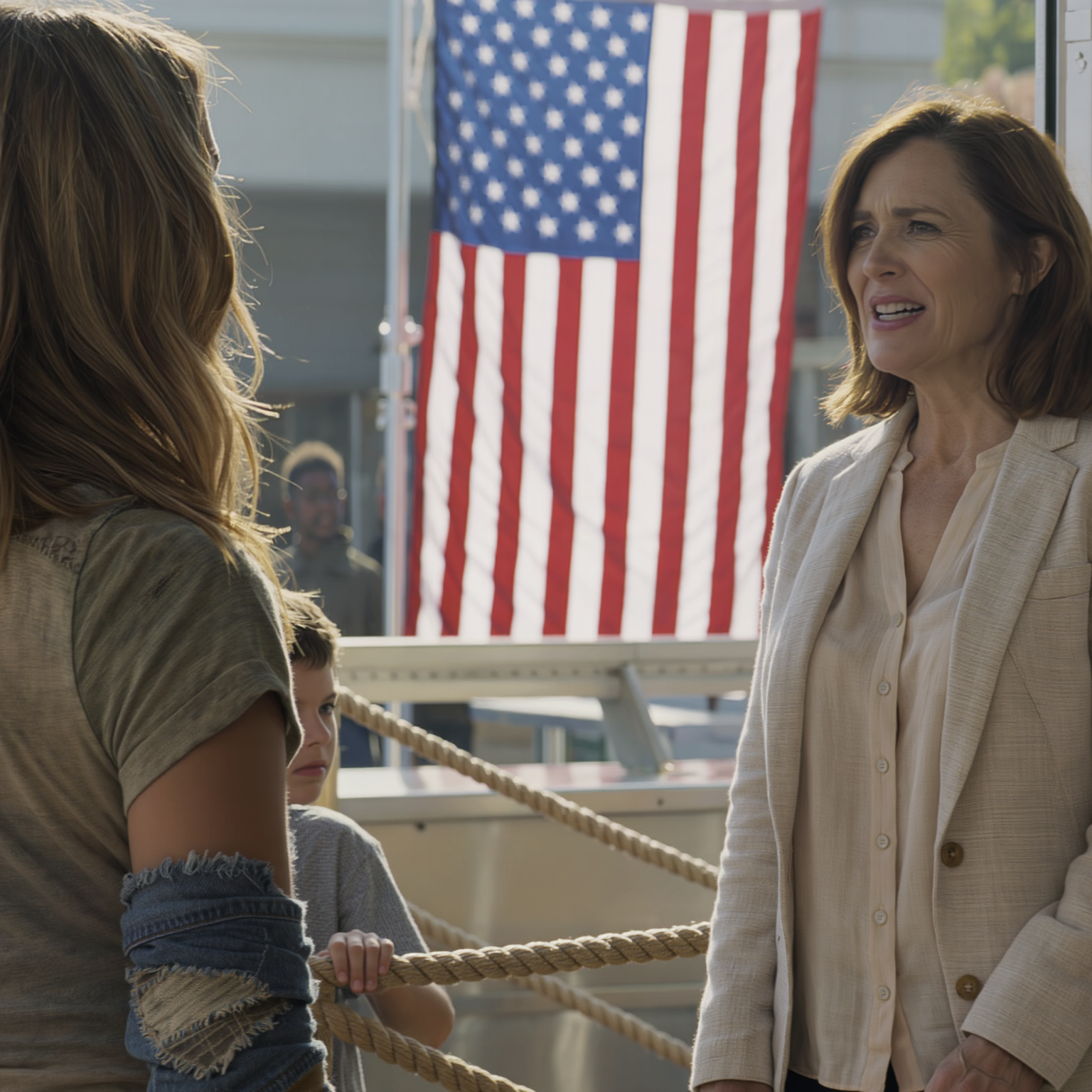

Sunday dinners in our family weren’t invitations; they were orders printed on the calendar in permanent ink. They kept the same hour, the same voices, the same choreography of praise and small humiliations. Since Mom had moved into the studio apartment above Lauren’s garage, my sister hosted as if she’d inherited a job title—Host—in a ceremony I had not been invited to attend. Lauren liked the optics: fairy lights strung along the fence line; melamine plates that photographed as porcelain; a table that said, We’re doing so well, thanks for asking.

At 5:30 on the dot, Daniel and I stepped from the driveway onto the flagstones, our footsteps tapping a measured rhythm. The air smelled like charcoal and July grass. Greg stood at the grill with the stance of a man pretending this was complex work: tongs in one hand, beer in the other, heat haloing his forearms. On the patio, Mom had the corner chair—the queen’s seat—wine in a stemless glass sweating into a ring on Lauren’s teak table. The twins ran shrieking arcs around the yard. Connor, twelve and certain, ruled the soccer ball like a minor deity.

“You’re late,” Lauren said in the doorway instead of hello, ponytail as taut as a rule. “It’s Sunday. There’s no traffic.”

“Hi to you, too,” I said lightly. “Traffic was fine.”

Daniel’s palm was small and damp inside mine. He squeezed once—the signal—and I bent to him, cheek grazing his soft hair. Kid shampoo. Sunshine. The safe smell of our house, carried like a talisman.

“Go play, buddy,” I whispered. He nodded and drifted toward the lawn the way a careful swimmer enters a lake—one toe, then another, feeling for ledges you can’t see. Connor flicked his gaze over him and then away. Assessed; dismissed.

Inside, the kitchen counters carried deli clamshells in a neat parade: potato salad, coleslaw, beans glossy with sugar. Store-bought rolls in a plastic sleeve. Lauren liked to curate a look of effortlessness—everything simple, everything easy, nothing cheap. She used the word elevated the way other people use please.

“Need help?” I asked, because I always asked.

“Grab the slaw,” she said, phone wedged into her shoulder while she narrated her to-do list to someone who must have asked for it. “Greg! Plates!”

Mom followed me in, glass already refreshed. “How’s work?” she asked the refrigerator door.

“Busy,” I said, stacking forks into a mason jar because that’s how Lauren liked them to look—rustic as if the mason were an actual man we knew. “Good.”

“Still at the hospital?”

“Yes. I’m managing the billing department.”

“That’s nice.” Nice like a room painted beige. “Stable.”

Stable: a word people use when the thing you do holds their life up. Stable when I negotiated her appeals. Stable when I co-signed her car. Stable when the hearing clinic said pay now or wait three months and I said now. Stable when money needed to appear and someone needed to know which form to submit and how to say the words in a tone insurance companies obey.

Greg shouldered in with a platter of chicken lacquered in bottled sauce. The twins materialized at the table, all elbows and shining knees. Connor slid past Daniel at the slider, taking the first chair as his due. The grill smoke clung to him like a cologne he hadn’t earned.

“Daniel, next to me,” I said, touching the chair to my right.

Connor snorted—teenage music played a year early. “Why does he get to sit by the adults?”

“Because I’m his mother,” I said, voice steady, “and I said so.”

“He should sit at the kids’ end.” He flicked his eyes to Lauren: permission-seeking disguised as defiance.

“Connor, don’t be rude,” Lauren said, but a smile pulled at the corner of her mouth like a draft through a window that won’t seal. Agreement, if you knew how to read it.

We ate. The twins talked over each other about an art project and a class pet. Connor complained about a math teacher who, according to Connor, didn’t understand math. Greg outlined a promotion track like a weather report: conditions favorable, clouds possible. Mom praised Lauren’s hosting skills—how she arranged, how she curated, how she made.

Daniel ate in small, exacting bites, organizing the plate into quadrants, then into smaller units, a cartographer of poultry. He breathed quietly. He always breathes quietly at these dinners, like he is paying rent for his oxygen.

“How’s school, Daniel?” Mom remembered him the way you remember a pot on a back burner when the smell changes.

“Good,” he said with the effort of being heard. “I like reading.”

“Reading’s important,” she said, already turning back to Lauren. “So, for the fundraiser—”

The conversation flowed on. It always did, a river that knocks you off your feet and calls it swimming.

After the plates were mostly bones and crumbs, the kids scattered back outside. Habit made me stack dishes.

“Leave those,” Lauren said, eyes on her phone, thumb pulling a bright river up the screen. “Greg will get them later.”

“I don’t mind.”

“I said leave them.”

I set the plates back down precisely where they’d been and sat, swallowing a heat that rose and then quieted like a scolded dog. Mom refilled her wine. Greg drifted to the living room to watch a game that sounded like men running and numbers changing. Through the glass, the yard tilted toward evening. Connor kept the ball like a secret. The twins chased him because that was the game: not soccer; Connor.

He blasted a shot. The ball clanged against the fence near where Daniel hovered, the chain link vibrating, a metal hum.

“Get that!” Connor yelled. Not a request. A test.

Daniel fetched and threw. Connor caught and tossed to a twin without looking. “You’re supposed to kick it, dummy.” The word dropped like a coin in a jar everyone pretended not to hear.

The twins laughed because laughter is the currency of admission.

Color crept into Daniel’s face. He turned for the house.

“Sensitive,” Lauren observed, clinical as a checkbox. “Kids need thicker skin.”

“He’s six,” I said. I wanted it to sound like a fact, not a defense.

“Connor was tougher at six,” she said, pride folding itself into the sentence.

Daniel came in and leaned into me, aligning his breath to mine like a metronome we both could follow.

“Mom, can we go soon?” he whispered.

“Soon. It’s rude to leave right away.”

Connor came in with his water bottle. He looked at Daniel the way you look at something you might return without a receipt. “Why is he always so weird?”

“Connor.” My voice had edges.

“What? He doesn’t play right. He doesn’t talk. He just stands there.”

“He’s shy,” I said.

“He’s weird.” Connor filled, capped, and went back out, satisfied with the echo he’d left.

Lauren kept scrolling. Mom kept not intervening.

“He could be more social,” Mom said finally, as if making a diagnosis she intended to bill for. “Might help him make friends.”

“He has friends.”

“Does he? Connor’s never seen him with anyone at school events.” She stirred her wine in small circles, as if she could spin me into agreeing.

“Different grades, different classes,” I said.

“Still,” she said, that word that erases all the words before it, “a child should be more outgoing. Maybe sports. Something to toughen him up.”

Daniel’s shoulder pressed harder into mine. Children are stenographers; they take down contempt in shorthand and never misspell it.

“He’s fine as he is,” I said.

“You’re too soft,” Mom said, with the authority of someone whose version of “backbone” had, in our childhood, sounded like a belt leaving a drawer. “Boys need structure. Discipline. My generation knew how to raise strong boys.”

“Your generation also thought hitting kids built character,” I said evenly.

“Don’t be dramatic.”

“What I’m being,” I said, standing, “is finished. Daniel, jacket.”

“It’s not even seven,” Lauren said, glancing at the microwave clock like a judge at a swim meet.

“We have things to do.”

“You’re being sensitive,” Mom said. “No one meant anything by it.”

“Connor called him weird twice,” I said. “You said he needs to toughen up. Lauren called him sensitive. I’d say the meanings were clear.”

“Boys tease,” she said, lifting her glass. “It’s normal.”

“Except he’s your grandson and Daniel’s your grandson, and you only defended one of them,” I said, and right then Connor appeared in the doorway like a cue.

“Grandma,” he asked dove-eyed, “is Aunt Claire leaving because of me?”

“No, sweetie,” Mom said quickly. “Your aunt is just—Jess.” My sister’s name fell out instead of mine.

Connor looked at me, then shaped his mouth around two words and pointed toward the door so the meaning would travel even without sound.

Trash belongs outside.

The twins giggled. Lauren’s lips parted, then pressed together, a half-second of almost that never found its sentence. Mom’s face showed surprise but not disapproval. From the living room, Greg yelled at the TV.

No one said stop. No one said that isn’t who we are. No one turned toward a child and taught him anything except that silence is permission.

“Daniel,” I said evenly, “we should go.”

He nodded. I nodded once—to the room, to the door, to my own spine—and took his hand. We left.

In the car, Daniel buckled himself with slow hands, eyes on the middle distance. Outside, sprinkler heads ticked in other people’s lawns. A neighbor shut a car trunk with the thud of completion. The sky matched the color of dishwater.

“You okay, buddy?” I asked when the silence had sat long enough to be true.

He took one of his careful breaths—the kind he uses to build sentences. “Why did Connor say that about you?”

“Because he’s twelve,” I said, keeping my voice flat as a safe road, “and he doesn’t understand how words bruise.”

“But nobody told him to stop.”

“I know.”

“Grandma didn’t say anything.”

“I know.”

“Does that mean they think you’re trash too?”

“What they think doesn’t decide what’s true,” I said. “Does it matter what I think?”

“Very much.”

“What do you think?”

“I think you’re the best mom,” he said in the tone you reserve for arithmetic. “And they’re mean.”

“Thank you,” I said, and a small warmth lit behind my ribs. “That’s all that matters.”

At home, we let routine carry us: bath, pajamas, two chapters of the mouse detective, a glass of water arranged on the nightstand like a spell against thirst. I tucked him in—blanket turned neatly at the top edge; Mr. Patches under his left arm because the right is for turning pages. He slept in thirteen minutes. I counted; I always count.

In the living room, the lamp made a soft circle on the rug. The fern in the corner looked like a creature trusting the sun. I opened my banking app.

The scheduled transfer sat there like a metronome: $3,200 on the fifteenth of each month. I could picture the night I set it up as if the app still contained fingerprints from 2017. Cold weather. Mom at my table, narrow shoulders rounded, tears making grooves on her cheeks. “I’m not ready to be poor,” she’d said, and I’d said, “You won’t be, not while I can help.” I had a salary and a skill set. I knew the cords of the system and how to pull them. It felt like being a good daughter and an adult at the same time, a double-portion of virtue.

Seven years turned a favor into policy. Seven years taught everyone to expect the river to run and to be angry at the shore when it didn’t.

I looked at the number. I looked at my son’s closed door. I watched the line between the two sharpen until it cut cleanly.

The phone buzzed.

Mom: Monthly transfer today.

No apology. No question about Daniel. No acknowledgment of what had just occurred under her watch. Just the calendar asking me to be the same person I had always been.

I typed three words.

Not my concern.

Then I deleted the automatic transfer. Deleted her account from my saved recipients. The app asked, Are you sure?—as if I had ever been more sure of anything.

I opened my laptop and started building the thing I know how to build: a clean ledger, numbers aligned like soldiers, columns like ribs. Dates. Amounts. Purposes. $3,200 × 84. The hearing aids. The dental work. The moving-day furniture she called “investments.” The auto loan statements with my name under CO-SIGNER like a tattoo I wanted removed. Screenshots of insurance email chains where my voice put on its suit and tie. Provider notices listing me as financial guarantor; I typed the sentence I have seen a thousand times and now meant for myself: Effective thirty (30) days from the date of this letter, I revoke any authorization designating me as guarantor for future services. Existing balances remain pursuant to agreements already executed.

I saved: Brennan_Support_Ledger_2017–2024.pdf. The cursor blinked, a small heartbeat. For a second, I let the room be quiet enough to hear my own.

Then I went to bed.

At 8:30 a.m. Monday, I sent the email.

Subject: Financial Support Documentation (2017–2024)

To: Mom; Lauren; Greg; Kevin

Attached is a ledger of all support provided to Patricia Brennan from Nov 2017 through Nov 2024. Monthly transfers: $3,200 × 84 = $268,800. Additional payments (medical, auto co-sign, furniture, hearing aids): estimated ≈ $30,000+. Approximate total outlay: ~$300,000.

Effective immediately:

- Monthly transfer canceled.

- Auto loan: I’m pursuing co-signer release. Borrower must refinance in her sole name by [date] or surrender the vehicle. Until refinance/surrender, existing liability remains per contract.

- Medical guarantor: I revoke for services after [date]; existing balances remain per current agreements.

This decision is final and not subject to negotiation. — Claire

By 9:00, my phone rang. By 10:00, seventeen text messages frothed onto the screen: Mom: We need to talk. Lauren: What is this? You can’t just stop supporting Mom. Kevin: Call me immediately. Greg: Let’s be reasonable. Lauren again: Mom is crying. You are being cruel. Mom again: Please call me. We can work this out.

I answered none of them. At noon, Kevin called from Oregon where the coffee is good and the people believe disagreeing is a sport you can win with logic.

“Have you lost your mind?” he said, skipping hello.

“No,” I said. “I’ve regained it.”

“You can’t just cut Mom off.”

“I didn’t cut her off,” I said in my work voice, the one that always persuades me first. “I stopped funding optional lifestyle expenses. She can live on her income. I did the math.”

“She can’t survive on sixteen-hundred a month.”

“She can,” I said. “Her expenses are modest. Apartment rent: zero—she lives in Lauren’s over-garage studio. Car payment: $412. Car insurance: $28. Health insurance supplement: $360. Utilities: about $150. Food and incidentals: about $500. Total: $1,630. Her income: Social Security $1,042; pension $618; total $1,660. She’s thirty dollars to the good.”

“What about emergencies?”

“I’ve covered seven years of emergencies,” I said. “Your turn.”

“I have my own family.”

“So do I,” I said. “A son who watched his grandmother sit quietly while his cousin called me trash.”

“Connor said that?” Kevin’s voice thinned—shock with a thread of defense stitched through it.

“He mouthed it,” I said. “Pointed at the door. Everyone saw. No one corrected him.”

“He’s twelve.”

“Exactly old enough to be corrected,” I said. “By adults who know what adults are for.”

“And your solution is to destroy Mom’s security?”

“My solution is to stop volunteering to be used,” I said. “To reassign resources to the one person I am obligated to protect.”

“She’ll lose her car.”

“Then she doesn’t need one,” I said. “She barely drives.”

“What about her quality of life?”

“What about mine? What about Daniel’s?”

Silence. I could hear his coffee machine clicking itself off.

“Are you cutting everyone off?” he asked.

“I’m cutting off the money,” I said. “The family cut me off a long time ago. Sunday just clarified the minutes.”

He exhaled. “Okay,” he said finally. “I hear you.” It wasn’t agreement. It was the sound of someone realizing the conversation had moved to a room where he didn’t have a key.

After Kevin, calls came in waves I let break on voicemail: Lauren first, then Greg, then Mom again. I didn’t touch a single notification. A boundary isn’t a vote. It’s a line you write straight.

Tuesday morning, the lender emailed in the chirpy tone corporations use when they’re about to be a problem. Patricia Brennan’s payment is past due; as co-signer, you are being contacted. Please advise.

I called. Held. Listened to an instrumental from a decade ago that had survived every elevator. When a human arrived, I put on the voice that solves things: calm, precise, unafraid of policy.

“I’m pursuing removal as co-signer,” I said. “The borrower will need to refinance in her name. If she cannot qualify, she will surrender the vehicle. I understand liability remains until refinance or surrender. I will not be making the payment.”

The representative read the script in a kind voice, the way a priest reads absolution: steps, dates, documents. We scheduled an appointment. We acknowledged consequences. We said thank you like professionals. When the call ended, the room hummed with the absence of hold music. My own pulse sounded loud and even.

Tuesday afternoon, Lauren arrived at my front door, anger arranged neatly on her face. The screen cut her into squares.

“Mom’s panicking,” she said.

“That tracks,” I said.

“Claire, be reasonable.”

“She needs to live within her means,” I said.

“She’s seventy-two.”

“I’m thirty-eight,” I said. “And I have a six-year-old who needs a mother who protects him from rooms where adults smile while he gets hurt.”

“Connor was being stupid.”

“And you were silent,” I said. “Which is worse.”

“I didn’t know what to say.”

“Try this: That’s unacceptable,” I said. “Or: Apologize right now.”

“I wasn’t smirking.”

“You were smiling,” I said. “I saw it. He saw it.”

“This is so selfish.”

“This is oxygen,” I said. “You have yours. I’m keeping mine.”

She left with a sound like a lid put on too tight. The house exhaled after her.

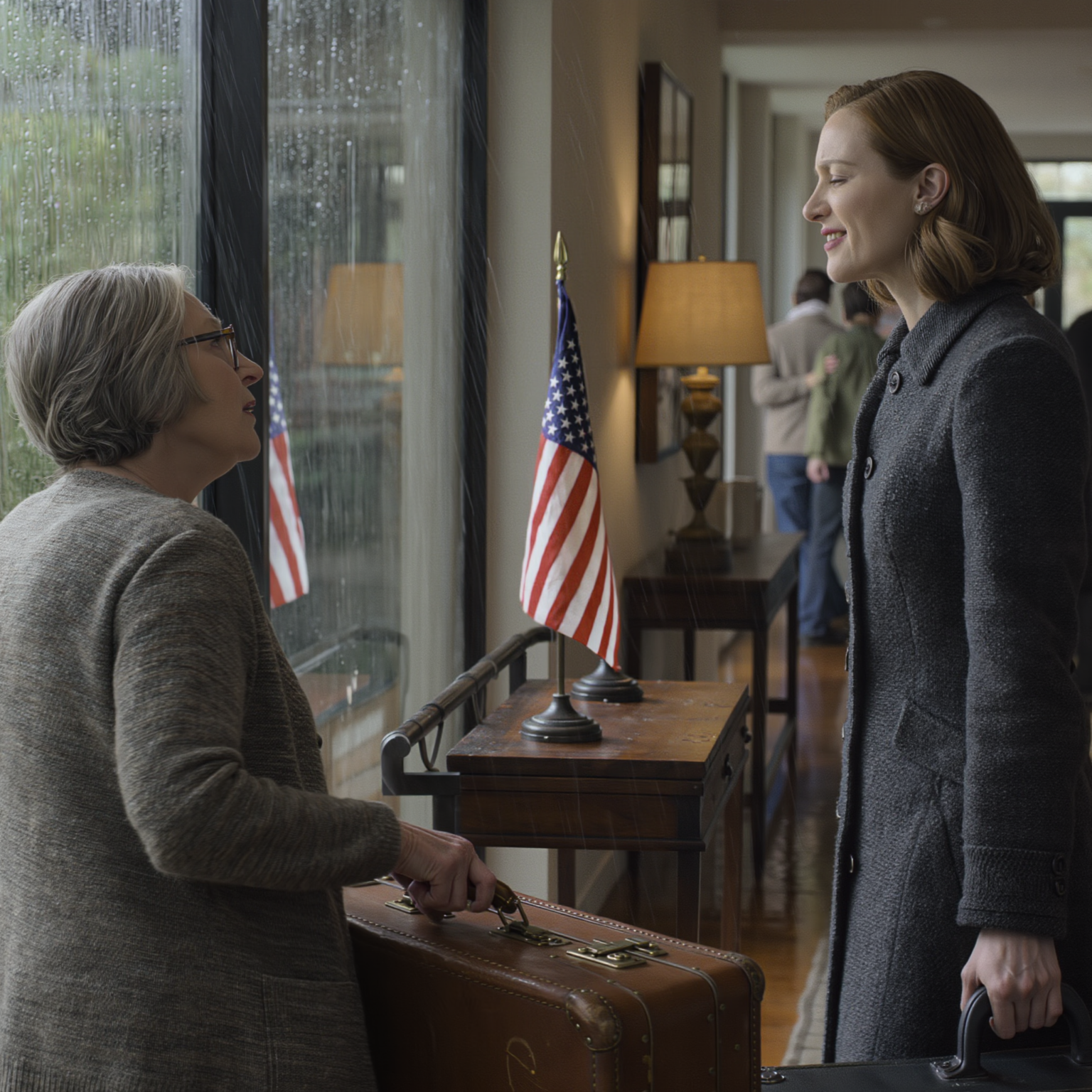

On Wednesday, Mom called from Lauren’s phone. I answered because there are calls you avoid until you can’t.

“Please,” she said, the word bending. “I’m sorry. Connor was wrong. I should have said something.”

“Yes,” I said. “You should have.”

“But cutting off all support,” she said, “that’s so extreme.”

“Is it more extreme than watching your grandson call me trash?” I asked. “More extreme than texting me for money after?”

“He didn’t call you trash,” she said quickly, reaching for the plank labeled Technicality. “He said—”

“He said ‘trash belongs outside’ while pointing at me,” I said. “He’s a child who learned from the adults around him that Claire is less. That she pays anyway.”

“That’s not—”

“You didn’t teach it with words,” I said. “You taught it with silence. With always taking Lauren’s side. With accepting my money like I’m a debit card with opinions.”

“I love you,” she said, and the word love hit the floor without a chair to sit on.

“Love isn’t a word,” I said. “It’s an action. Your actions told me I was worth $3,200 a month but not worth defending. So now you get neither.”

“What can I do to fix this?”

“Nothing,” I said. “It isn’t fixable with an apology seven years late.”

“I’m your mother,” she said. “And Daniel is your son.”

“The one you watched being hurt,” I said, “and said nothing. I’m protecting him now the way you should have protected me then.”

I hung up. Sometimes mercy is a click.

Thursday morning, the car line at school moved in little ovals of progress. When Daniel slid into the back seat, his backpack bumped the door and his smile landed square.

“Good day?” I asked.

“Really good,” he said. “I didn’t think about Sunday at all.”

“That’s wonderful.”

“Are we still going to Grandma’s for dinner?” He asked it like a scientist checking his math.

“No,” I said. “Not for a while.”

“Good,” he said, fast, then softer: “I didn’t like them anyway.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Because you said family is important,” he said. Not accusing—reciting. “I didn’t want to make you sad.”

“Family is important,” I said, “but we get to choose what it means. And it doesn’t mean spending time with people who hurt us. Even if they’re related. Especially if they’re related.”

“Okay,” he said. “Can we have our own Sunday dinners? Just us?”

“Absolutely. What do you want to eat?”

“Pizza,” he said. “And a movie. And nobody will call us weird.”

“Perfect,” I said, and in the mirror I watched his shoulders lower slightly, as if permission had physical weight.

Sunday arrived like a clean shirt. We did not drive to Lauren’s. We did not pack politeness or patience. We stayed home.

Daniel chose pepperoni and mushrooms. I added a salad because habit is a kind of love. We ate on the couch, napkins dangling, plates balanced on knees. The TV glowed with a movie about a boy who finds a dragon in the woods and keeps it safe by believing in it harder than the world can argue. We laughed without glancing at each other to check if laughter was permitted.

No twelve-year-old called anyone trash. No grandmother asked for money. No mandatory dinner pretended that fine was a flavor we all enjoyed.

I tucked him in early. Bliss exhausts children. In the quiet living room, I watered the fern and watched the fronds shiver like they were practicing gratefulness and found it easy.

On Monday—the eighth day since I stopped the transfer—I checked my phone while the kettle thought about boiling. No messages from Mom asking for money. No emergencies that used to arrange themselves on my shoulders. Somewhere across town, she was learning how to live on what she had. Somewhere else, a lender’s office had a folder with her name on it. Somewhere else, a boy slept without worrying about the words he heard.

Trash had taught itself to stay outside. Inside my house, where it was warm and kind, only things that recognized us belonged.

At work, I opened a file and wrestled with an insurance portal until it did the right thing. Words became lines that became yes. The same muscle I had always used—moving systems with language—now served me, too. I ate a sandwich at my desk and deleted three voicemails from Lauren: We’re sisters; Mom can’t refinance; if the car is repossessed it will ruin her credit. The arguments tried on three outfits. The body stayed the same.

The lender sent a follow-up confirming the refinance appointment and the required documents. I forwarded it to Mom with a single sentence: Here are the steps to proceed; please coordinate directly with the lender. I didn’t add the sentence that begins with I’m sorry. I had written I’m sorry in dollars for seven years.

At pickup, Daniel ran to the car waving a drawing. The sky in his picture was purple because sometimes the sky is, and the word HOME marched across the top in careful capitals. He buckled in with the speed of someone learning to trust routines again.

“Pizza again next Sunday?” he asked, auditioning the shape of a tradition.

“We’ll rotate,” I said solemnly. “Pizza, tacos, pancakes for dinner.”

He laughed. “Pancakes for dinner is silly.”

“Silly is another word for free,” I said, and he liked that enough to repeat it softly to himself, like a spell.

That night, after dishes and a load of towels, I opened the ledger again like a book I was almost ready to finish. Numbers are their own kind of poetry if you let them be: 3,200 × 84. $268,800. Plus the hearing aids. Plus the dental work. Plus the co-pays with names of providers stacked like a roll call. The winter of new tires I called a present. The spring of the insurance denial I turned into a yes because I knew which phrase to quote from the policy. The summer of the car loan I signed in a finance office that smelled like carpet cleaner and a man barely old enough to rent a car explaining APR to me as if I were new to arithmetic.

I thought about explaining coins to Daniel: this is a nickel, worth five; this is a dime, worth ten; yes, it’s smaller. Worth isn’t about size. He had looked up at me with his serious eyes and said, “Like the words people use.”

“Exactly,” I’d said. “Exactly.”

In the bathroom mirror, I met my own eyes. “I have you,” I told the woman there. “I have you.” I said it once for the girl I used to be and once for the boy down the hall. The words held.

The next morning, Mom texted not about money but about paperwork—What papers do I need—and I sent the list. Then I put my phone face down and listened to the house being a house. The refrigerator hummed like a machine that trusts its job. Somewhere a dog barked at a mail truck and then apologized by being quiet. The light moved an inch along the floorboards. My life fit.

It would be tidy to end the story with a ceremony of consequence—keys turned in, apologies issued, a check mailed as a symbolic reverse current I could frame and never cash. Tidy belongs to spreadsheets and curated feeds. Life prefers the edge of a page.

Here is what I know: I cannot purchase a better version of other people with money. I cannot buy respect or rent it monthly. I can only price admission to my life at what it actually costs me and enforce it without flinching.

Here is what I know: on Sunday nights now, our house smells like garlic and cartoons. Daniel sets two plates and then gives Mr. Patches a napkin because everyone at dinner should have a napkin. We talk about the kid in his class who is learning English and how Daniel taught him the word for basketball by dribbling in the hallway during indoor recess. We laugh at a joke that isn’t funny because laughing together is practice.

Here is what I know: when my phone rings on Mondays, I let it. When the kettle whistles, I answer that instead. When someone mouths words that used to decide me, I choose differently.

And when my son takes my hand—outside a house, inside a question, at the margin of a room—I squeeze back, and we walk toward the car, and I drive us home.

There is a script to American courtesies, and my family loved to perform it as if language were a cul-de-sac—looping back where it started. On that patio, the script wore summer. “You’re late.” “Traffic.” “No traffic on Sundays.” The lines served like plastic forks: convenient, unsharp, destined to snap under pressure. I used to believe if I delivered my lines perfectly, the audience would clap. What I know now is that some rooms do not reward accuracy. They reward volume. They reward whoever fills the air fastest.

I could catalog the scene down to molecules—the way the bottled sauce burned at the edges into sugar, the tannin bite of a merlot purchased for its label, the way Connor’s gel left a neat seam above his ear where the comb had passed. I could tell you about the chair legs rasping on the slate, the fork that pinged when someone set it too quickly on a plate, the gnats orbiting the candle that was supposed to keep them away. None of these details is an event. They are the texture of permission. They are the background hum that says: carry on.

My sister’s smile—the one she can deny later—started as a twitch and held like a pose the camera would capture if it were invited. We keep two kinds of smiles in my family: the ones we mean and the ones we keep for optics. The latter are a currency. You can pay a lot of debts with them if the room is willing to let you.

When Connor called my son weird—when he graded another human boy as if he were an assignment—it wasn’t the word that did the work. It was the non-reaction. Twelve-year-olds test fences. Adults build them. That night, the fence was missing and the test became the rule.

If I could show you the ledger as something other than a PDF, I would place it in your hands so you could feel the weight of ordinary generosity. Not the grand gesture—no scholarships endowed, no houses purchased outright—but the slow, rhythmic choreography of adulthood. Auto-debits and mailed checks, insurance appeals and follow-up calls. A life funded by the person in the room who knows how to remain on hold without forgetting why she called.

I built the document the way I build a case for a denial overturned: no flourish, no adjectives, just dates and verbs that behave themselves. Nov 15, 2017: ACH transfer $3,200. Dec 15, 2017: ACH transfer $3,200. Repeat, repeat, repeat—until the rhythm itself argues. Then the interstitial notes: Apr 2, 2019: Paid invoice—hearing aids—provider ref #…; Aug 26, 2020: Co-signed vehicle loan—account #…; Jan 11, 2022: Dental crowns—out-of-pocket after plan max—$…

There is a music to numbers when you read them aloud. They count not only money but minutes. Each line is a choice I made instead of another choice. Each choice is a direction. Maps are made from that.

I included exactly one sentence that carried anything like heat, and even then I dressed it in policy’s clothes: Effective thirty (30) days from the date of this letter, I revoke any authorization designating me as guarantor for future services. Existing balances remain pursuant to agreements already executed. You can’t light a match in an insurance portal, so you learn to carry flint.

How boys learn: They watch. If a room tolerates a cruelty, a boy learns cruelty belongs. If a room interrupts it, a boy learns interruption is what adults are for. Daniel watched and learned two things at once that night: how to leave, and how to decide. Leaving is a decision; deciding is a leaving.

He is six and already understands more about oxygen than some grown men. He looks for it in rooms. He measures how much is left for him.

On the drive home, the stoplights measured us out in red and green. At a long red, I glanced over and saw his reflection layered on the passenger window—his face and the porch lights of a block we didn’t live on sliding together into a single, temporary boy. “Am I weird?” he asked not that night but another night when the house was quiet and the word had cooled enough to touch. “Yes,” I said. “In ways I love. In ways that make you you.” We counted good weirds together: the way he lines up his crayons by gradient, the way he hears the refrigerator hum and can tell when the door seal isn’t quite right, the way he laughs at the wrong part of a joke because he heard a better one hiding underneath.

The phone is a theater where people rehearse the version of themselves they prefer. Kevin on Monday liked to play Reasonable Man Confronts Irresponsible Sister. He brought facts that weren’t, and I brought math that was. He brought the fear that money would move and leave him exposed to requests. I brought the notion that the request had been answered for seven years and was now answered differently.

There is a particular silence you hear when someone realizes their argument is not landing. It is not the silence of defeat; it is the silence of inventory. People check which tools they still have and choose a new one. Kevin chose family. We’re family. Translation: obligation. I did not disagree. I changed the definition: Family is not a license to harm without consequence. Family is a license to stay if you can behave.

When I said boundary, he heard punishment. When I said oxygen, he heard selfishness. We were speaking the same language and saying different things, which is another American tradition.

At the lender, the policy exists not to feel but to function. I do not resent that. Things that function reliably are easier to navigate than people who don’t. The representative read the steps the way a priest parses the liturgy: Proof of income, driver’s license, insurance, title, refinance appointment, interest rate contingent upon creditworthiness, cosigner release conditional upon approval. Consequences colon. Deadlines colon. A clean sentence can be mercy when the rest of your week has been smirks.

The hold music was a song I had hated in 2013 and forgiven by 2017 and now recognized as an old colleague: we keep meeting in elevators and on apology lines and while canceling services I no longer use. When the line clicked and the voice returned, I felt the simple rightness of being the person who does not flinch around paperwork. Paperwork is how you move a wall when your hands alone can’t budge it.

When Lauren stood at my screen door, the sun made a grid across her forehead. She looked like she was inside a comic strip panel, each square available for a different emotion. She chose indignation first. Then pleading. Then the old sister move of telling me about myself as if I hadn’t met me.

“This is so selfish,” she said. People love the word selfish when another person finally opts out of being used.

“This is oxygen,” I said. “You have yours. I’m keeping mine.”

I have learned not to monologue at a door. Doors like verbs: open, close, lock. I have learned that leaving room for someone else’s better self is different from leaving room for their behavior. One is hope; the other is leakage. On the porch, Lauren picked hope because it costs less to carry. “We’ll talk later,” she said, which means: I will try another tool. I wished her luck and meant it. I wish better tools for everyone.

Mom’s sorry arrived with the edges still damp. “Connor was wrong. I should have said something.” Yes, and yes. The second sentence is the one that matters. A grandmother has exactly three jobs in a moment like that: stop the harm, comfort the harmed, and teach the harmer what a boundary feels like. She did none of the three.

When she reached for technicality—He didn’t say you were trash—I saw the way we had all been taught to survive in our original house: find the loophole that keeps the roof on. The problem is that loopholes also let the weather in.

“I love you,” she said. Love as an unadorned noun never did much work in our family. It was the sentence used to end the scene, the blackout line. I wanted a verb. I wanted: I will call him back in and correct him. I will apologize in front of your son so he hears me value you. I will mean it. I will change something.

Instead, she wanted me to change the outcome without changing the premise. I have done that trick with insurance denials and pre-auths, with prior histories and balance write-offs. It works on forms; it fails in families. In families, the premise is the story. If you don’t change it, the ending never sticks.

The first new Sunday dinner felt like a room we had only peeked into before and now were allowed to live in. Daniel chose the movie and the pizza place and the spot on the couch where he can reach the light switch without getting up. We negotiated the number of napkins (two, one for each of us, plus a third for Mr. Patches “just in case”), and we voted on whether mushrooms count as a vegetable. He declared that if they grow, they count. We are a representative democracy.

During the opening credits, he leaned his head on my arm in the way he does when he is not thinking about it. I memorized the weight. I have spent a long time memorizing weights I cannot share with anyone else because to name them is to invite a critique of my scale. In our house now, I can call things by their names.

When the dragon appeared—clumsy, soft, worthy—he gasped so loud it made me laugh. “He needs a nest,” Daniel said. “He needs a place where nobody calls him names.” We paused the movie and made nests out of the throw blankets. We paused and unpaused three times because learning what to do with comfort is a process.

On Monday mornings now, I have a ritual. I make coffee. I check my phone for fires that are not mine. I answer the kettle. I log into the insurance portal and become, for the required minutes, the person I am paid to be: fluent in denial codes and policy inclusions, precise with dates, impossible to discourage. Then I log out and become the person my son needs: elastic, specific, delighted by purple skies in crayon drawings.

I do not perform nobility for anyone. I am not the sacrificial daughter or the endlessly stable sister. Stability is not the same as durability. Bridges are stable until they crack where the weight has been applied for too long. Good engineers do not ask the bridge to be better. They change the load.

People have asked me—colleagues, a neighbor who caught the outline of the story and wanted to tuck it into a lesson she was building about boundaries—how I knew where to draw the line. The answer is not mystical. The line was always there. I just decided to see it. It looked like this: my son’s cheek against my arm. It sounded like this: silence where a grandmother’s voice should have been. It cost this much: $3,200 times 84, plus a shape of exhaustion I can’t cleanly quantify.

If you want a test, here is mine: When I imagine doing the generous thing, do I feel expanded or erased? If the answer is erased, the gift is not generosity. It is conscription. No one owes their life to the people who conscript them.

I have not added a single character to this account. The cast is exactly whom you think: a grandmother who forgot her job; a sister who learned the optics of care but not its grammar; a brother who prefers logic to repair; a man on a phone who read policy in a kind voice; a boy who needs a nest; and a woman who learned to call a ledger a story when that’s what it was. We will all continue in our lanes until one of us changes. I cannot make them. I can only maintain mine.

On some nights, I imagine an apology happening at a table I do not attend: Lauren telling Connor what the word outside does when you point with it; Mom practicing sentences in a mirror where love is both noun and verb; Kevin Googling cosigner release and realizing it requires more than a sister’s patience. On other nights, I do not imagine them at all. It is a relief to let other people be offstage.

There is a proverb I don’t quote because it’s been worn thin by people who use it to bless their leaving: “Build the life you want and invite people to meet you there.” I think about the sentence differently, with less poster-ready optimism. Build the life you can stand to inhabit. Invite the people who can stand to inhabit it with you. Do not lower the roof to make it easier for them to walk in without ducking. Do not make the door wider by removing the door.

On Sundays, we set two plates. On Mondays, my phone still rings. On Tuesdays, lenders send emails with bullet points and phrases like pending decision. On Wednesdays, a boy practices reading out loud and finds the rhythm of commas. On Thursdays, I water a fern that forgives me when I forget. On Fridays, I leave the porch light on a little longer than I need to, just in case someone I love has decided to learn a new sentence.

If you need a final image, take this: a hand on a knob, twice. The first time, on a Sunday evening, the knob turns away from a room that has forgotten its job. The second time, weeks later, the knob turns inward—into a smaller room where a boy is making a nest out of blankets, where a woman is learning she can breathe without counting the breaths she gives away, where a bear named Mr. Patches has a napkin because everyone at dinner has a napkin. The door closes. The house keeps its own weather.

What remains outside remains outside. What belongs inside, stays.