My Mother Told My Six-Year-Old, “Whatever Your Cousin Wants, You Give Her”—Right After Throwing Her Last Gift From Grandma Into The Fire.

That Sunday started the way “normal” is supposed to look in our quiet Midwest neighborhood—late September light sliding through the maple leaves, charcoal smoke drifting over the fence, the hum of a football game on a television inside somebody’s living room. A plane crossed the sky in a thin white line. Somewhere a dog barked once, then gave up. For about thirty minutes, I let myself relax and pretend we were that family—the harmless, slightly loud American clan with folding chairs, paper plates, and easy laughter.

My mother stood at the top of the social pyramid, of course, sitting in her favorite lawn chair near the back sliding door like it was a throne. She had on one of her “good” cardigans, the pale blue one that made her eyes look softer than they ever were when she opened her mouth, and a pair of white jeans that somehow stayed spotless no matter how many children ran underfoot.

To her left, in the second-most important chair, sat my sister, Madison.

Madison never just “sat.” She arranged herself, one crossed leg angled just so, ankle bracelet winking in the light, sunglasses pushed up into her perfect hair. If my mother was the queen, Madison was the crown princess, the one everyone was expected to orbit.

I did what I’ve done my whole life in that backyard: I noticed the arrangement, and I swallowed it.

I adjusted napkins. I checked the condiments. I flipped the hot dogs when my father got distracted watching the game highlights on his phone. I handed out juice pouches, made sure there were enough chairs, and asked people about their jobs while they told me, for the fourth year in a row, that Denver air must be different than Ohio air.

“I keep telling you,” my aunt Janet said, patting my arm over the potato salad, “one day you’ll move back. Your mother misses you so much.”

My mother did, in fact, miss me—my labor, my childcare, my reliable presence, my willingness to smooth things over. I was less convinced she missed me.

But that afternoon, I tried to set all of it aside.

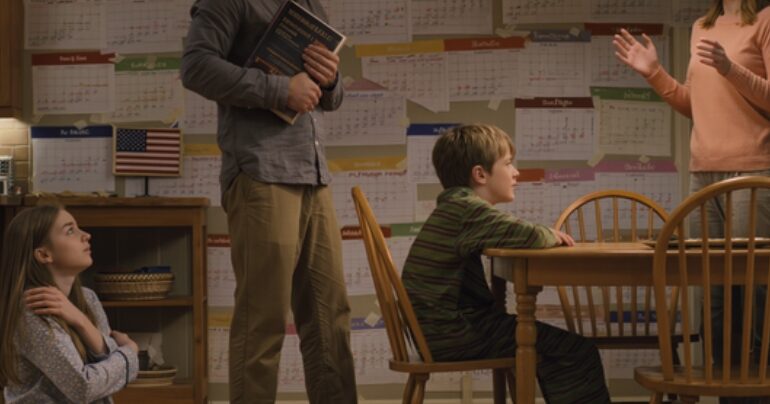

Emma, six years old and all knees and elbows, had flour on her cheeks from “helping” me bake cookies that morning. She wore a purple T-shirt with a unicorn on it and jeans with little silver stars stitched along the pockets. I’d braided her hair into two pigtails and tied them with mismatched ribbons because that’s what we had in the drawer.

In her hands, she clutched a small plush unicorn—white body, rainbow mane, a golden horn that had gone slightly crooked from too many bedtime squeezes. The fur along its neck was matted in places where tears had dried. Its embroidered eyes were a little worn, one thread starting to come loose at the corner so it looked like it was always mid-wink.

It had been the last gift from her other grandmother—my ex-husband’s mother—before she passed the previous winter. We got the package two days before Christmas, the return address in Florida, the inside lined with tissue paper and smelling faintly of lavender.

“For my Emma,” the note had said in looping handwriting. “So she always has a little magic with her. Love, Grandma Rose.”

Emma had carried that unicorn everywhere since. To school. To bed. To the dentist. On the plane when we flew home from Denver to Ohio for visits like this one, its threadbare mane peeking out from under her arm as she slept.

“Do you want to leave Sparkle at home today?” I’d asked that morning, trying to sound casual. “She might get dirty.”

“She likes parties,” Emma had said, serious as a judge. “Grandma Rose said she’s brave.”

I almost told her no. I almost said, “She’s special, let’s keep her safe today,” because a part of me that I had learned not to listen to knew that “special” things did not fare well in my mother’s orbit.

Instead, I chose hope over experience.

“One day,” I’d told myself, “they’ll surprise you.”

Besides, it was just a cookout. Just hamburgers and hot dogs and a bowl of grapes sweating on the picnic table. Just family.

I wanted one day off from being on guard.

So I nodded and tucked Sparkle’s tail under Emma’s arm.

“Okay,” I said. “She can come. But she stays in the yard, and she doesn’t go near the food.”

“Yes, Mommy,” Emma said solemnly, already spinning a little circle in the kitchen so the unicorn could “see” her dress.

Now, in my parents’ backyard, she found a quiet patch of grass under the oak tree near the fence and sat cross-legged, her back to most of the commotion. From where I stood at the grill, I could see her lips moving, eyes fixed on her toy.

She was narrating something—a quest, a tea party, a rescue mission. Six-year-olds never just play; they create universes with their toys as the citizens. Her voice came out in a soft little stream of words that the grown-ups ignored and the cousins periodically disrupted.

Lucas, my three-year-old, was running circles around the folding chairs with the younger cousins, squealing every time one of them pretended to “get” him. He wore his favorite dinosaur shirt, already stained with ketchup, and tried to keep up with kids a head taller.

He fell once, skinned his knee, and popped back up, more annoyed than hurt.

“Shake it off, buddy,” I called.

“I’m brave,” he announced, and kept running.

My mother raised her plastic cup toward Madison’s.

“To family,” she said.

“To family,” Madison echoed, clinking.

The word floated across the yard and landed with a little thud near my ribs.

I told myself to breathe.

I flipped the burgers. I smiled. I handed a plate to my father.

“Medium, right?” I asked.

“Still know me,” he said, chuckling, like I’d remembered some rare, intimate detail instead of the fact that he’d ordered medium since I was old enough to understand what “doneness” meant.

Madison’s daughter Olivia wandered near the grill, tossing her hair the way nine-year-olds do when they’ve already figured out that their hair is a weapon.

“Auntie,” she said, “is there any more cheese? I want extra.”

“Ask Grandma,” Madison called from her lawn chair without turning around. “She knows where everything is.”

Olivia rolled her eyes and sauntered off toward the kitchen.

I watched Emma under the tree, bouncing Sparkle on her knee, and felt… almost peaceful.

“Looks like a picture,” my aunt Janet said, following my gaze. “Little ones, big tree, sunshine. You’re blessed, honey.”

“I know,” I said. And I did. In some ways.

I was blessed. With two healthy kids. With a job I mostly liked. With a decent apartment in Denver and friends who didn’t treat me like background music.

What I wasn’t blessed with was a mother who understood how to hold more than one daughter in her hands at once without squeezing one too tight.

“Tell me about Denver,” Janet said, tugging on my sleeve. “My friend is thinking about a cruise to Alaska. Can you believe it? I told her to do one of those Rocky Mountain train trips instead and—”

Her voice dipped into the familiar, comfortable hum of other people’s plans. I half-listened, half-counted heads: one, two, three, four cousins by the swing set; Lucas near the garden; Emma under the tree.

I almost stood up when I saw Olivia drift toward my daughter, that unicorn radar in her eyes. The kids had been told: “No taking other people’s toys.” But Olivia tended to interpret rules as suggestions if they inconvenienced her in any way.

“It’s fine,” I told myself. “She’s nine. She knows better. And I’m three steps away.”

And that’s when my aunt asked about the cruise, and I did the one thing my nervous system had been begging me not to do all day.

I sat back down.

It couldn’t have been more than a minute.

Maybe less. Just enough time for Janet to ask, “Is it better to book flights on Tuesday or Wednesday?” Just enough time for me to explain that it didn’t matter as much as she thought if she was always waiting for the perfect deal.

When I looked back at the oak tree, Emma was no longer sitting.

She was running.

Her feet pounded the grass, her pigtails flying behind her, eyes wide and wet. Her cheeks were flushed, and she clutched empty air in front of her like there was supposed to be something in it.

“Mommy!” she cried, the sound cutting through conversation and over the hiss of the grill. “Mommy, my cousin’s trying to take my precious toy. Can you tell her to stay away?”

Her voice broke on “precious.”

My muscles moved before my brain caught up. I stood, hands still smelling like burger grease, wiping them on my jeans and reaching for her shoulders.

“What happened?” I asked, crouching.

Olivia sauntered over behind her, Sparkle in hand, gripping the unicorn by one back leg so its head dangled upside down.

“We’re sharing,” Olivia said. “Grandma says we have to share.”

Emma shook her head so hard her braids flew.

“She took her!” she sobbed. “She just took her and wouldn’t give her back. Grandma says I have to share with Olivia even if I don’t want to. But Sparkle is mine.”

I opened my mouth.

I know exactly what I was going to say. I was going to tell Olivia to hand the toy back. I was going to explain, in that calm, non-negotiable mom tone I’d been practicing, that sharing does not mean “I take something you love because I want it.” I was going to say that Sparkle had been a gift from someone who wasn’t here anymore, and we treat those things with extra care.

I was going to say all of that.

But my mother’s voice cut across the yard before I got a single word out.

“What did you say?” she snapped, sharp and fast.

The whole backyard seemed to tilt in her direction.

She didn’t wait for an answer.

She didn’t ask whose toy it was. She didn’t say, “Girls, what’s going on?” or “Let’s all take a breath.” She didn’t ask, “Emma, why are you crying?”

She stood up from her lawn chair with a speed that belied her age, marched across the grass in sandals that never seemed to get dirty, and planted herself in front of us.

“Give that to me,” she said to Emma, holding out her hand.

Emma clutched the unicorn tighter, finally managing to grab hold of it from Olivia’s lax grip, pressing it to her chest.

“No,” she whispered. “Grandma, please. It’s mine.”

My mother’s eyes flashed.

The children nearby went silent. Even the cousins at the swing set slowed down, sensing a change in the air. The football game from the living room TV floated through the screen door, the announcer’s voice suddenly too loud and far away.

“Don’t you tell me no,” my mother hissed.

She reached forward and wrenched the unicorn out of Emma’s hands with one sharp tug.

Emma let out a sound I had never heard from her before—half gasp, half cry, a little animal noise ripped from somewhere deep. Her hands closed on empty space.

“Mom,” I said, straightening, my heart pounding. “Give it back. You don’t understand—”

My mother turned on her heel and headed for the fire pit.

The flames popped and breathed in the center of the backyard, contained by a ring of stones my father had bought from a home improvement store ten years ago. Bits of charred wood shifted and cracked, sending up a shower of sparks.

“Mom,” I said again, louder. “Don’t.”

She didn’t look back.

She held the unicorn by one leg over the fire, the rainbow mane catching the light for one last moment.

“This will teach you about sharing,” she said, as casually as if she were tossing another piece of kindling onto the flames.

Then she opened her fingers.

For the rest of my life, I will hear the little collective gasp that went up from the kids nearest the pit. The wet thump of lightly stuffed fabric hitting the burning logs. The quick curl of synthetic fur in seconds. The way the rainbow mane shriveled into a twisted black line, releasing a thin, acrid smell that layered itself over the charcoal smoke.

Sparkle’s golden horn bent and darkened. One stitched eye, for a moment, looked up through the heat before melting into a vague blur.

Emma’s scream stopped every conversation on the lawn.

It wasn’t loud, not compared to the music or the TV or some of Madison’s stories that always seemed designed to fill every corner of a room. But it was… total. It emptied the space around it. It made my hands go numb.

I moved to pull my daughter toward me, to get her away from the fire, from my mother, from the sudden, awful heat.

But my mother stepped faster.

She pivoted back, closing the distance between them in three quick strides.

“Don’t you dare start crying like that,” she said, and before my brain could register what was happening, her arm swung.

The sound of her open palm on Emma’s cheek is something my nervous system will always recognize, no matter how many years pass. A flat, clean crack in the autumn air, followed by a beat of stunned silence.

Emma’s head snapped to the side. Her body swayed.

For a second, she didn’t make a sound at all, like someone had pressed pause on her.

Then a red mark rose on her cheek in the shape of my mother’s hand.

“Don’t you ever disobey your cousin,” my mother spat, her voice carrying across the yard. “Whatever she wants, you give her. Do you understand me?”

For a heartbeat, the whole yard went blurry—the grill, the picnic table, the faces looking everywhere but at us.

My father stared down at the burgers like he could will them to be more interesting.

My aunts studied their paper plates as if they’d never seen potato salad before. Someone fiddled with a plastic fork, the prongs bending back and forth.

Madison stood behind our mother, arms crossed, a small smirk settled on her face like jewelry.

Something cold and hard settled in the back of my throat.

I didn’t think.

I just acted.

I stepped between my mother and my daughter, put my hands gently on Emma’s shoulders, and pulled her against me. Her small body shook, sobs coming now in jagged bursts, each breath hitting my collarbone.

“What is wrong with you?” I heard myself say.

My voice sounded… steady. Too steady. Like it was coming from someone else entirely, someone with more practice than me at confronting the woman who had raised her.

No one answered.

My mother’s eyes flashed, offended more than ashamed.

She held out her hand, palm up, imperious.

“Just give me money,” she said briskly, as if we were settling a bill at the grocery store. “I’ll buy a brand-new toy for my precious granddaughter.”

She tilted her head toward Olivia, who stood with her arms wrapped around herself, eyes wide but dry.

As if grief could be replaced with a receipt.

As if the problem was plastic, not the person who had thrown it into the fire and slapped a child for crying.

“Absolutely not,” I said.

The words came out smooth, like I had practiced them in the mirror.

“You destroyed something irreplaceable,” I went on. “You hit my daughter. And you want me to pay for it?”

“She was being selfish,” my mother snapped. “We don’t raise selfish children in this family.”

My father shifted his weight from one foot to the other.

“She could’ve let Olivia play with it for five minutes,” he muttered. “It’s just a toy.”

Emma’s fingers dug into my shirt, twisting the fabric.

“It was from Grandma Rose,” she sobbed into my chest. “She gave it to me and then she went to sleep and didn’t wake up.”

I felt her tears soaking through the cotton.

“It wasn’t ‘just a toy,’” I said. “It was a gift from someone she can’t see anymore. It was comfort. It was… hers.”

My mother’s mouth tightened.

“We’ll get her another one,” she said. “Bigger. Better. You’re making a scene, Rebecca.”

There it was—the old accusation.

You’re making a scene.

You’re blowing things out of proportion.

You’re the problem here.

I looked around the yard.

At my father, who still wouldn’t meet my eyes.

At my aunts, who shifted their weight from one foot to the other, lips pressed tight.

At my cousins, who pulled their children a few inches closer without making it obvious, eyes sliding away when mine reached theirs.

At Madison, whose expression said everything she didn’t need to say out loud.

This is what happens when you don’t fall in line.

“This is my child,” I said. “I’m allowed to make a scene when my child is hurt.”

“Then get out,” my mother shrieked, her control finally slipping. The pitch of her voice rose high enough that I saw the neighbors’ curtains twitch. “You and your brat are no longer welcome here.”

The word hit me in the chest.

Brat.

She’d never said it about Emma before.

About me, yes. About children on television. About kids in grocery stores. But not about my daughter. Not like that. Not in front of her.

“Don’t you call her that,” I said quietly.

“You did this,” my mother went on, breath coming faster. “You turned her into this. Talking back. Acting like she’s special. That’s your influence. Not mine.”

“Good,” I said.

The word escaped before I could filter it.

“Good?” she repeated, incredulous.

“Yes,” I said. “Good. Because if you think what you just did is what a grandmother should do, then I want exactly none of your influence on my children.”

We stared at each other, the space between us thick with all the things we’d never said.

“You’re really going to walk out over a toy?” she scoffed.

I adjusted Emma’s weight on my hip, her cheek pressed against my shoulder, the heat of the slap still radiating through my shirt.

“This isn’t about a toy,” I said. “This is about what you taught every child in this yard in the last five minutes.”

My voice didn’t rise, but it carried.

“You taught them that the older, louder kid gets whatever she wants,” I said. “That if someone says no, you can take it anyway, and the adults will back you up. That if a child cries when you destroy something precious to them, you are allowed to hit them and call them names. That their feelings are disposable. That their boundaries mean nothing. And that the people who hurt them will be defended by the people who were supposed to protect them.”

I could feel every eye in the yard on us now.

My mother’s cheeks flushed.

“You’re being dramatic,” she said. “Like always. You twist everything to make yourself look like a martyr.”

I looked at my father.

“Dad?” I said. “Anything to say?”

He cleared his throat.

“Let’s all calm down,” he said. “It’s a nice day. No need to ruin it. Your mother just got carried away. We’ll get a replacement. Rise above it, Jess.”

Rise above it.

The phrase landed like another slap.

“Rise above it,” I repeated. “While she hits my daughter?”

I laughed once, the sound short and sharp.

“No,” I said. “Not this time.”

I turned to Madison.

“Anything?” I asked. “No thoughts at all about your child trying to take a toy and your mother throwing it into the fire?”

Her smirk deepened.

“Maybe if you’d taught your daughter to share, we wouldn’t be here,” she said. “You know Mom’s rules. You don’t come into her house and disrespect her.”

A thousand childhood memories flashed through my head like a fast slideshow: toys taken out of my hands because “you’ve had it long enough, let your sister have it now”; desserts “reassigned” at the table because “Amanda likes that more than you”; vacations scheduled around her dance recitals while my debate tournaments were penciled in if there was time.

My mother’s house.

Her rules.

Everyone else, even children, expected to bend.

The oak tree cast a dapple of sunlight across the grass, the leaves shifting in a breeze that suddenly felt colder than it had ten minutes before.

Lucas toddled closer, sensing something wrong, his dinosaur shirt smeared with mustard.

“Mommy?” he said, voice small. “Can we go home?”

“Yes,” I said.

I turned, and in one sweep, I gathered our things.

The diaper bag. Lucas’s little sneakers from under a chair. Emma’s jacket from the back of the bench. I glanced once at the fire pit, at the blackened lump that had been Sparkle, and forced myself to look away before the image burned any deeper.

“Where do you think you’re going?” my mother demanded.

“Home,” I said, slinging the diaper bag over my shoulder. “To somewhere you don’t get to hurt my children and call it discipline.”

“If you step out that gate, don’t bother coming back,” she said, her voice low and shaking. “I’m done chasing after your dramatics. I’m done walking on eggshells. You think you’re better than us now, with your Denver job and your little apartment? Fine. Go be better somewhere else.”

The thing about people who live in a constant state of their own grievance is that they genuinely can’t comprehend that someone might leave without wanting to come back.

“Okay,” I said.

Her eyes widened, just a fraction.

“Okay?” she repeated, like she’d misheard.

“You said don’t come back,” I said. “I’m listening.”

My father shook his head.

“You don’t mean that,” he told me. “You’ll cool off. Your mother will cool off. In a week, this will all blow over. Don’t say anything you’ll regret.”

I looked at Emma’s cheek, the shape of a hand still there, faint fingers trailing toward her ear.

“I’d regret staying,” I said.

No one moved to stop me as I walked toward the side gate.

The hinges squeaked, the metal scraping slightly where the wood had swollen from last week’s rain. My father had always said he’d fix it “next weekend,” and next weekend had somehow not arrived in three years.

I stepped onto the driveway gravel, the little stones crunching under my shoes. The sound of the backyard—voices, music, the faint hiss of the grill—dimmed behind me.

In the rearview mirror of my own life, I saw myself at eight, at twelve, at sixteen, walking that same path with my shoulders a little hunched, clutching something that mattered to me while adults decided how much it mattered in front of everyone.

I buckled Emma into her booster seat in the back of my car, her hands still trembling. She clutched the seat belt like it was a rope on a ship in a storm.

Lucas climbed into his car seat with unusual quiet, eyes wide, sensing this wasn’t the time for dinosaur noises.

I knelt beside Emma’s seat, my knees pressing into the gravel.

“Sweetheart,” I said softly, “look at me.”

She lifted her face. Her cheek was still flushed. One little patch of skin already looked puffy, just under her eye.

“We’re going home now,” I said. “We’re not going back in the yard. You’re safe with me.”

“Why does Grandma hate me?” she whispered.

Her words pierced some last remaining piece of denial in me.

“She doesn’t—” The old reflex rose automatically, ready to soothe and explain and smooth. I bit it down. I was done lying on my mother’s behalf.

“Grandma doesn’t… understand how to be kind,” I said instead. “She loves in a way that hurts people. That’s not your fault. She doesn’t hate you, Emma. She doesn’t know how to treat kids fairly.”

“Why did she burn Sparkle?” Emma asked, tears spilling again. “Grandma Rose gave her to me. She said I was brave. I was sharing Sparkle with the tree. That’s not a bad thing.”

It took me a second to understand what she meant.

Sharing Sparkle with the tree.

That’s what she’d been doing under the oak, introducing her unicorn to the branches and the bark and the bugs and the little slice of shade.

Because in the world of six-year-olds, sharing is not about surrender. It’s about inclusion.

“You didn’t do anything wrong,” I said. “You said no when someone tried to take something very special from you. That’s allowed. That’s good. I’m proud of you for saying no.”

“Grandma said I’m selfish,” she whispered, voice shaking. “She said I don’t know how to share. Is that true?”

Again, the old reflex—explain, soften, excuse—pushed at my teeth.

“Grandma is wrong,” I said.

The words felt strange and right all at once.

“What she did was wrong,” I went on. “Adults can be wrong sometimes. Even grandmas.”

She frowned, brow furrowing the way it did when she tried to sound out a tricky word in her reading homework.

“Will she say sorry?” she asked.

I thought of my mother’s face, the hard set of her jaw. The way she’d defended herself by calling my daughter selfish and me dramatic. The years of non-apologies, of “I’m sorry you feel that way” and “let’s just move on” and “why can’t you let things go?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “But whether she does or not, I’m not letting her be alone with you anymore. That’s my job. To keep you safe.”

“Even from Grandma?” she whispered.

“Especially from Grandma,” I said.

She blinked, absorbing that.

“I miss Sparkle,” she said, and the full weight of it hit me—the finality of melted synthetic fibers and scorched stuffing.

I swallowed against the lump in my throat.

“Me too,” I said. “And we’re going to remember her. We’re going to talk about her, and we’re going to find a way to carry her with us, even if we don’t have the toy.”

“Like a ghost?” Lucas piped up from his car seat.

“Like a memory,” I said. “Like a story.”

I closed the door gently and walked around to the driver’s side.

My hands shook as I put the key in the ignition.

As I pulled away from the curb, I checked the rearview mirror one more time.

The backyard was mostly hidden behind the fence. I could just see the top of the oak tree, its branches reaching over like it wanted to know what had happened beneath it.

On the drive back to our rental apartment, Emma was quiet, fingers worrying at the hem of her shirt. Lucas sang to himself softly, an off-key version of a song from his favorite cartoon.

The radio played some seventies ballad my parents would have called “real music.” I turned it off.

A few blocks from home, at a red light, Emma spoke again.

“Mommy?” she said.

“Yeah, baby?” I asked, eyes on the light.

“Are we in trouble?” she asked.

The idea that she could even consider that—that we might have been the ones at fault for leaving—made something inside me clench.

“No,” I said firmly. “We are absolutely not in trouble. We made a good choice.”

“What choice?” she asked.

“The choice to leave a place where someone hurt you and called you names,” I said. “We’re allowed to leave those places. Always.”

Even when the place is your childhood home.

Even when the person is your mother.

At home, I got the kids inside, shoes in the entryway, bag on the hook. I made them peanut butter sandwiches with apple slices, the quickest comfort food I could manage while my brain buzzed.

I snapped a picture of Emma’s cheek while she blew on her sandwich to cool it, trying to make it casual.

“Do a silly face,” I said, and she stuck her tongue out without thinking.

Click.

The slap mark was captured along with the silliness, a small red handprint preserved on my phone.

After lunch, I set them up with a movie on the couch and an extra blanket, something light and gentle, nothing with conflict or loud noises. Emma curled on one side, Lucas on the other, both pressed against my thighs.

Within minutes, the exhaustion of crying and adrenaline pulled them under. Their breathing deepened. The cartoon voices faded into a soft buzz.

I sat there between them, one hand resting on each small leg, and let the quiet settle.

The part of me that had been a child in that backyard wanted to call someone.

My mother, to beg her to see what she’d done.

My father, to demand that he fix it.

My aunts, to ask “Did you see that? Was I crazy? Did that really happen?”

Another part of me, newly awake and stubborn, told that old voice to sit down.

They had shown me who they were, again, in a way that could no longer be packaged as “old-fashioned” or “strict” or “from another generation.”

So I did something my mother never expected me to do.

I wrote everything down.

Not in my head. Not in an imaginary speech I’d never give. Not in a text to a friend that could be dismissed as “gossip” later.

On paper.

At our small kitchen table, the one covered in crayon marks and the faint outline of a spill from last year’s science experiment, I opened a spiral notebook and picked up a pen.

I wrote the date.

Then I wrote:

Backyard cookout at Mom and Dad’s. 2:17 p.m., Emma and Olivia near the oak tree. Sparkle present.

It felt ridiculous for the first few lines, like I was filing a report at work instead of chronicling what had just happened in my family’s yard.

But I kept going.

Time. Words. Witnesses. I listed who was where. Who saw what. Who looked away. Who spoke, and what they said. I wrote down the exact phrasing of my mother’s words.

“This will teach you about sharing.”

“Don’t you ever disobey your cousin.”

“Whatever she wants, you give her.”

“Just give me money.”

“You and your brat are no longer welcome here.”

I described the fire pit. The unicorn. The slap.

I paused, pen hovering above the page, wondering if I was exaggerating, if my language was too harsh.

Then I looked at my phone, at the picture of Emma’s cheek, the faint shape of fingers visible even under the kitchen light.

I kept writing.

I listed everyone who had been in the yard: Dad at the grill. Aunt Janet near the potato salad. Uncle Paul by the cooler. Three cousins clustered near the swing set. Madison behind Mom. Olivia near the fire.

I left blank lines after each name where I could fill in, later, whether they’d said anything when given the chance.

I flipped to a fresh page and wrote:

Three things my mother has always loved more than my boundaries:

-

Being obeyed.

-

Being admired.

-

Being right.

The words stared back at me, both petty and profound.

I thought about all the times she’d said, “Children don’t talk back,” when what she meant was, “Children don’t get to say no.”

All the times she’d called me dramatic for crying when I got hurt.

All the times she’d punished me for telling the truth about something that made her look bad.

Maybe, if it had just been me, I would have found a way to swallow it again.

But it wasn’t just me anymore.

It was Emma’s trembling hands and whispered questions. Lucas’s wide eyes. The way every child in that yard had watched a grandmother throw a precious toy into the fire and then slap the child who dared to scream.

If the people who watched in silence wouldn’t speak up, then the proof itself would have to.

For the first time in my life, I started thinking about my mother not just as “Mom,” but as a person whose choices might need to be documented.

Not for revenge.

For protection.

I opened my laptop next.

I created a folder on the desktop and named it “Backyard 9-24.” A bland, neutral label that wouldn’t raise anyone’s eyebrow if they saw it.

Inside, I saved the photos.

The picture of Emma’s cheek, silly face and all.

A picture I’d snapped of the fire pit from the kitchen window while the kids watched their movie, when I’d gone outside, under the pretense of taking out the trash, and zoomed in on the blackened, melted lump among the charred logs.

The background of that photo showed three lawn chairs, one of them empty, one of them with a familiar blue cardigan draped over the back.

I copied the notes from my notebook into a document, cleaned up the typos, and added more detail now that the emotional fog had lifted enough for the memories to sharpen.

Then I opened my email.

The first message I wrote was to Natalie—a friend in Denver, another mom from Lucas’s daycare, the person who had seen enough of my family dynamics over the years to know when I was downplaying things.

Subject line: I need you to read this so I don’t gaslight myself.

I typed the story again, this time in letter form, letting the sentences flow more naturally, adding the texture that the bullet points had stripped out.

I hit send before I could second-guess myself.

The next email took longer.

I opened a new message and addressed it to the school counselor at Emma’s elementary school back in Denver. We were flying home in three days; by the time Emma sat at her little desk again, the red mark on her cheek would be gone. But the story behind it wouldn’t be.

Subject: Incident with maternal grandmother / concern for Emma’s emotional safety.

I stared at the blinking cursor.

I am not the type of person who complains about family to strangers. I am the one who nods and smiles and says, “Oh, you know how parents are,” even when a part of me wants to scream.

But I thought about Emma sitting on the carpet in the counselor’s office someday, trying to explain why she flinched when someone raised their hand too fast. I thought about the counselor trying to piece together the picture with only half the puzzle.

So I wrote.

I kept it simple and factual. No adjectives I wouldn’t be comfortable reading out loud in a courtroom someday, if it ever came to that.

I described the backyard.

My mother’s actions.

The slap.

Our decision not to allow unsupervised visits anymore.

“I’m not asking you to intervene directly,” I wrote at the end. “I just want there to be a record, in case Emma shows distress at school or speaks about this incident. I want her to have safe adults who know that when she says, ‘Grandma threw my unicorn in the fire,’ she is not making it up.”

I read it twice, breathing shallow.

Then I hit send.

The third message, the hardest one, I addressed to my parents.

I didn’t send it that night. I drafted it, deleted half of it, rewrote it, and left it sitting open in a tab to marinate.

At the top, I wrote:

You told me to get out and never come back. I heard you.

Then I explained, as calmly as I could, what their actions had meant from my vantage point, and from Emma’s.

“This isn’t about a toy,” I wrote. “It’s about your choice to hurt my child—emotionally and physically—to enforce obedience to your favorite grandchild. It’s about you siding with the child who takes instead of the child who says no. It’s about you throwing something precious in the fire to prove a point, then demanding money as if this is a customer service issue instead of a breach of basic safety and trust.”

I told them I would not be bringing the kids to their house again any time soon.

That any future contact would be in public, with others around.

That there would be no more sleepovers, no more “just drop them off for the afternoon” visits, no more giving them the benefit of the doubt.

I told them that if they wanted a relationship with my children, there would need to be an apology—real, not the “sorry you feel that way” variety—and an acknowledgment that what happened was wrong.

Not the kind of wrong that gets brushed off with “we all overreact sometimes.”

The kind of wrong that gets written down.

I saved the draft.

Closed the laptop.

And finally let myself cry.

I cried for Sparkle. For the small, brave unicorn who had been a bridge between Emma and a grandmother she missed every night.

I cried for six-year-old me, who had never had anyone step between her and that slap.

I cried for my father, who had chosen looking at burgers over looking at what his wife had done.

For my aunts, who had chosen their own comfort over speaking up.

For Madison, who had smiled from the sidelines as her child was defended and mine was sacrificed.

And I cried for my mother, who had been given so many chances to be better and had chosen, again and again, to be right instead.

At some point, I noticed the edge of the kitchen table digging into my forearms and realized I’d been hunched there for a long time.

I got up, rinsed my face with cool water at the sink, and walked back to the couch.

Emma and Lucas were still sleeping, heads tipped toward me, bodies curved like commas.

I sat down between them and gently placed my hands on their backs, feeling the slow rise and fall.

“Grandma Rose,” I whispered into the air between us, “if you wanted to make sure Sparkle kept her promise, you chose a good day to send a reminder.”

Because that’s what this was, in some strange way—a reminder.

That my loyalty to my mother did not have to override my obligation to my children.

That boundaries are not disrespect, no matter how many times someone from an older generation says so.

That leaving a backyard cookout is not the end of the world.

It’s the beginning of a different one.

The next morning, my phone buzzed before I’d even had coffee.

Natalie.

Her reply to my email was long and full of the kind of fury it’s easier to feel on someone else’s behalf than on your own.

“I am so sorry,” she wrote. “That is not normal. That is not okay. You are not overreacting. If anyone did that to my kids, I would never see them again.”

She listed all the specific pieces of the story that had made her chest hurt when she read them.

“The worst part,” she wrote, “is not even the slap. It’s that she punished Emma for saying no. Please, please keep writing this down. Abusers rely on everyone forgetting.”

Abusers.

The word made my stomach twist. I’d always thought of that as something that happened in other families. On the news. In “serious” stories.

Not in quiet backyards with maple trees and plastic cups.

Not with grandmothers who brought casseroles when babies were born.

Not with mothers who sat in lawn chairs and toasted “To family.”

But I left the word there, in my brain, without pushing it away.

Because maybe that’s what this next part of my life would be: learning how to tell the truth about my family without dressing it up for public consumption.

Around noon, the school counselor replied.

“Thank you for letting us know,” she wrote. “I’m so sorry this happened to Emma. We will make a note in her file and keep an eye out for any signs of distress. Please feel free to reach out if you notice changes in her behavior that you’d like to discuss. You are doing the right thing by protecting her.”

You are doing the right thing.

Four words I didn’t know I’d been waiting to hear until I read them on the screen.

That afternoon, after the kids had built a pillow fort and “decorated” their room with stickers I’d hoped to save for a rainy day, my email from my parents came.

The subject line was simple.

RE: Yesterday.

I stared at it for a good thirty seconds before clicking.

Rebecca,

Your dramatics never cease to amaze me.

I did not “abuse” your child. I disciplined my granddaughter for being rude to her cousin. In our family, we do not raise selfish children who hoard their toys and talk back to their elders.

You embarrassed me in front of everyone. You shouted. You stormed out. You made a scene and upset the little ones far more than a slap on the cheek ever could.

When we were raising you, if our parents had thrown out every toy that caused a fight, we would have been called strict, not abusive. We turned out just fine. You’re making a mountain out of a molehill, as usual.

If you want to apologize for your behavior, my door is always open. But I will not be told how to discipline children by someone who lets them run all over her.

Mom

My father had added a single line at the bottom.

We love you, kiddo. Let’s all cool down.

Dad

I sat back in my chair.

There it was.

No remorse.

No acknowledgment.

Just manipulation, minimized harm, and an invitation to step back into the role I’d held my whole life: the one who smoothed things over, who took on the responsibility of keeping the peace.

I closed the email without replying.

Then I opened the draft I’d started the night before.

I took out half the hedges and disclaimers. Deleted the “maybe I’m overreacting” sentence I’d written out of habit. Removed every “but” that undercut my own experience.

I added one paragraph at the top.

Mom, Dad,

I am not writing this for a fight. I’m writing it because, for once, I want there to be a clear record of what happened, from my perspective, in words that are not immediately drowned out by yours.

Then I let the rest stand.

At the end, I added:

This is not an ultimatum.

It is a boundary.

We will be flying back to Denver on Wednesday as planned. Until further notice, there will be no unsupervised time between you and my children. No visits at your house. If you come to see us, it will be in public places, or at our home, with ground rules we agree on ahead of time.

If you are ever ready to acknowledge that what happened was wrong and to apologize to Emma, we can talk more. Until then, I will not debate this with you.

Rebecca

I hit send.

Then I shut the laptop.

I expected the guilt to rush in immediately, like it usually did when I dared to stand up to them.

It didn’t.

Guilt did show up later, of course—like someone who’d missed the first bus but caught the second. But it wasn’t the overwhelming kind that knocked me off my feet.

It was a smaller, more manageable feeling. One I could hold in my hand and examine.

Whose voice is this?

Is it mine, or is it hers?

When Emma woke from her nap, her cheek was less red. The mark had faded to a faint pink, like the ghost of a handprint.

“Does it still hurt?” I asked.

She touched it gently.

“A little,” she said. “Mostly when I think about it.”

“That makes sense,” I said. “Sometimes feelings hurt more than the actual hit.”

She nodded, accepting that.

“Can we draw Sparkle?” she asked. “So we don’t forget her?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Let’s do that.”

We spread paper and crayons on the living room floor.

She drew a white unicorn with a rainbow mane, a horn that sparkled, and a little heart on its side.

“I’m adding the heart,” she explained, tongue sticking out slightly in concentration, “because she loved me.”

When she was done, she wrote, in big, wobbly letters at the top: SPARKLE. BEST FRIEND.

I drew one too, less for me than for her, sketching as best I could the goofy tilt of the head, the way the mane had always refused to lie flat.

We taped them to the fridge.

Later, when we flew back to Denver and fell into the routine of school and work again, those drawings stayed there.

Every time I reached for the milk, I saw them.

Every time I packed a lunch, every time Lucas asked for yet another snack, every time Emma showed a friend where the markers were, Sparkle’s crayon face watched us.

A little memorial in colors that didn’t burn.

In the months that followed, my mother sent a few texts.

Pictures of toys in store aisles, captions like: “Would this make it up to her?” and “See? Grandma can buy her something even better!”

I didn’t respond.

She called once, but I let it go to voicemail.

“You can’t keep the kids from us forever,” she said in the message, her tone half wheedling, half threatening. “They need their grandparents. You’re punishing everyone over one little incident.”

One little incident.

I saved the voicemail in the same folder as the photos.

My father sent an email on Thanksgiving.

We’re setting an extra place in case you change your mind, he wrote.

We love you.

The kids will be asking for you.

I read it out loud to Mark at our own small table, where we’d set out a turkey breast instead of a whole bird, a pan of roasted vegetables, and a pie we’d bought from the bakery down the street.

“I used to believe that,” I said.

“That they loved you?” he asked gently.

“That the extra place was for me,” I said. “Not for the version of me they wish existed.”

“What version is that?” he asked.

“The one who doesn’t mind when her daughter gets hit,” I said. “The one who shrugs off a burned toy as ‘no big deal.’ The one who comes back, over and over, no matter how many times they throw something precious in the fire.”

I took a sip of wine.

“I can’t be her anymore,” I said.

He nodded.

“You never were,” he said. “You just tried very hard to pretend.”

We set two extra places at our table that day, by choice.

One for Grandma Rose, whose picture we propped against a glass and to whom we said, “Thank you for loving Emma with such steady gentleness.”

One for Sparkle, drawn in crayon and taped to the wall nearby.

Emma made a little toast with her sparkling cider.

“To the people who actually know how to share,” she said.

Lucas clinked his plastic cup against hers.

“Like me,” he said.

We laughed.

It wasn’t the family scene my parents would have approved of—no big table full of cousins and aunts, no football game blaring in the background, no hierarchy of lawn chairs.

It was smaller.

Quieter.

But it was ours.

And in that little house in Denver, far from the quiet backyard where maple leaves filtered the September light and a toy had disappeared in the flames, I finally understood something people like my mother never wanted me to know:

Not every invitation deserves a yes.

Not every backyard is a place you’re obligated to return to.

And not every person who calls themselves “Grandma” has earned the right to stand near your children without witnesses.

So when my mother threw my six-year-old’s unicorn in the fire and slapped her, when she said “Whatever she wants, you give her,” she thought she was cementing the old rule.

The golden child gets everything.

The quiet one gives.

The grown-ups decide what matters.

Instead, without meaning to, she lit a fuse under something else.

My patience.

My denial.

My willingness to sacrifice my child’s safety for my parents’ comfort.

That day in the backyard, a line got drawn.

In crayon on our fridge.

In ink on my notebook pages.

In the invisible ledger where I keep track of what I will and will not allow.

And when people ask me now why we don’t “go home” more often, why my kids don’t spend summers “with Grandma and Grandpa like we used to back in the day,” I tell them the truth, in whatever portion they’ve earned.

“Because my mother hurt my daughter,” I say, “and then told her it was her fault.”

If they press, if they say, “Surely it wasn’t that bad,” sometimes I tell them about the unicorn.

About the fire.

About the slap.

About the six words my mother said that I will never forget:

“Whatever she wants, you give her.”

And I tell them, with a calm I had to build from scratch, “I’m done teaching my children they have to.”

Then I turn back to my life, to my kids, to our small table and our drawn-on fridge and our evenings where the only things that go into the trash are leftovers and junk mail.

Not magic.

Not boundaries.

Not us.