I woke up in a strange facility with no memory of arriving. the nurse said i’d been there three days. i was 65, perfectly healthy, and confused. then i discovered the truth: my son had drugged me, had me committed, and sold my $850k house for $615k to his fiancẫe. so i turned his crime into his worst nightmare!

I woke up to the hum of fluorescent lights and the hiss of an oxygen concentrator that wasn’t mine. The ceiling above me was a flat, institutional white, the kind you see in office parks and government buildings, with a hairline crack that ran from the sprinkler head to the corner like a faint scar. The walls were a tired pale green. Somewhere down the hallway, a television played an old Sinatra song too softly for the lyrics to land, and on the far wall, above a laminated fire exit map, someone had taped a small picture of the American flag—fifty stars, a little faded, curling at the edges under cheap Scotch tape.

It smelled like antiseptic and overcooked vegetables and something else I couldn’t place yet. Something institutional. Not my house. Not my life.

I wasn’t in my own bed. The sheets were too stiff, the pillow too thin. When I shifted, the mattress made that rubberized squeak that says “property of” in tiny black letters on a metal tag.

A woman in pale blue scrubs walked past my open doorway, pushing a cart with little white cups and a plastic pitcher. She didn’t look in.

“Excuse me,” I called. My voice came out rough, like I hadn’t used it in days.

She stopped, reversed a step, and appeared in the doorway with a professional smile that didn’t quite reach her eyes. “Oh, Mr. Patterson, you’re awake. How are you feeling?”

“Where am I?” I asked.

“Riverside Extended Care Facility,” she said, like she’d said it a hundred times before. “You’ve been here three days now.”

Three days. Three days gone from my life like a chapter ripped out of a book. That was the first moment I felt a quiet, cold anger rise up under the confusion.

I pushed myself up slowly, waiting for the vertigo, the pain, the weakness that should have justified a place like this. Everything worked. My hands responded. My legs didn’t tremble. My head was clear.

“There’s been some mistake,” I said. “I don’t need to be here.”

The nurse came closer and checked the wristband I hadn’t noticed until then. It had my name—Richard Patterson—my birthdate, a barcode. “Your son Marcus signed all the paperwork,” she said gently. “He said you’d be confused at first. It’s normal to feel disoriented.”

“I’m not disoriented,” I said, enunciating each word like a test. “I’m sixty‑five, not ninety‑five. I had a dizzy spell a couple of weeks ago. My son insisted I see a doctor. The doctor said my blood pressure was high, gave me a prescription, and sent me home. That’s it.”

She patted my arm in that careful way people do when they think you’re fragile. “Well, if you need anything, just press the call button, okay? We’re here to keep you safe.” Her eyes slid away from mine, and I knew she’d already decided which version of reality she believed.

That was the moment I realized something was very wrong, and it wasn’t my memory.

After she left, I took inventory. My body felt fine, aside from the stiffness that comes from too many birthdays and one too many nights falling asleep in my recliner. My mind felt sharp. I could recite the names of all fifty states, backwards if you gave me enough time. I could still run orbital simulations in my head if you asked nicely. I was a retired aerospace engineer; I’d designed guidance systems for satellites that still circled above that faded little flag on the wall.

This was not confusion. This was a trap I didn’t understand yet.

“I need to call my son,” I told the nurse when she came back with a plastic tray of scrambled eggs and toast that tasted like cardboard.

“Of course,” she said. “Let me get you a phone.”

The phone she brought wasn’t mine. It was a black flip phone with oversized buttons, the kind marketed in late‑night commercials to “seniors who just want to stay connected.” I gave her Marcus’s number from memory. Some things age well.

He answered on the fourth ring. “Dad, I’m in a meeting,” he said, his voice clipped, background noise buzzing like a hive.

“Why am I in a nursing home, Marcus?” I asked.

Silence, like someone had pressed mute on his end.

“We talked about this,” he said finally. “You had another episode. The doctor said you needed round‑the‑clock monitoring.”

“What episode?” I said. “I feel fine. I want to go home.”

“Dad, you’re not fine,” he replied. “You fell. You were confused. The doctor…” He trailed off. “Look, we’ll talk about this later. I have to go.”

And then my only son hung up on me.

I stared at the flip phone, heavy and unfamiliar in my hand. It wasn’t the smartphone my granddaughter had bullied me into buying two years earlier so I could see her dance recital videos. This thing might as well have come out of a museum display about early twenty‑first‑century tech.

“Where are my belongings?” I asked the nurse when she came back for the tray.

“They’re in the secure storage room,” she said. “We keep valuables there so nothing gets misplaced. I’ll bring you what you’re cleared to have.” The word “cleared” stuck in my head like a splinter.

She returned with a small clear plastic bag, the kind they give you at the ER when they cut off your clothes and tape your wedding ring to the side. Inside were my wallet, my watch, and the gold band I’d worn since 1974, when Sandra slipped it onto my finger in a church decorated with cheap carnations and borrowed candles.

No phone. No house keys. No car keys. No glasses.

“Where’s my phone?” I asked.

“Your son took it,” she said. “He said you kept calling people and getting confused, worrying your neighbors.”

That was a lie. A clean, practiced lie delivered with a sympathetic tilt of the head.

I wasn’t confused. I wasn’t wandering the neighborhood calling 911 about raccoons. I knew exactly who I was and where I belonged. And it wasn’t here.

I decided, right then, that if everyone expected me to be confused, I could use that. I’d spent my career sending metal and fuel and mathematics into orbit. Playing slow for a few days was not beyond my skill set.

Over the next forty‑eight hours, I played along.

I took the medications they handed me in those little white cups with numbers written on the side. I pretended not to notice that my eyelids felt heavy not long after, that my thoughts got sticky at the edges. Later, I would learn the word for what they were giving me: benzodiazepines. Calming agents. Chemical handcuffs.

I attended the group activities. Chair yoga in the common room. Bingo at three. A “music memory” hour where a volunteer with a guitar played old standards while half the room stared at nothing and the other half dozed. I smiled at the staff. I asked polite questions. I watched everything.

The facility wasn’t the worst place I’d ever seen. It was clean. The floors shone. There were framed prints of lighthouses and mountain landscapes on the walls, the kind you buy in bulk online. The staff were adequately friendly, their smiles tired but not cruel. They were, I suspected, underpaid and overworked, doing their best inside a system that measured care in fifteen‑minute increments.

But this place was not for me. It was for people in wheelchairs who called every aide “honey” because they couldn’t remember their names. For people who asked for their parents every night, not understanding that those parents had been gone longer than I’d been alive. For people whose minds were finishing long, hard journeys.

I was just starting a very different kind of battle.

On the third day, sometime after lunch and before the sedatives from my noon “med pass” fully clamped down, my neighbor Helen appeared in the doorway.

“Richard, what on earth is going on?” she demanded, marching past the sign that said FAMILY ONLY beyond this point.

Helen Miller had lived next door to me for thirty‑two years. She was seventy, sharp as a tack, and had an eagle eye for trash cans left out past pickup day. She also brought over homemade chicken soup whenever she heard a siren on our street and had a wicked sense of humor about HOA rules.

She looked furious.

“Marcus came by last week with a moving truck,” she said without preamble. “He told me you’d had a stroke and were going to live with him. I offered to help pack, but he said he had it handled. Now I find out you’re here?”

“Moving truck?” I repeated slowly, my heart pounding behind my ribs.

“They cleared out your house,” she said. “Furniture, everything. Richard, I tried to call you. Your phone went straight to voicemail. When I asked Marcus if I could visit, he said you weren’t up for visitors and that the doctors wanted you calm.” Her expression softened, just for a second. “I came anyway.”

My house. The house I’d built with my own hands in 1985, right after Sandra died and I realized that if I didn’t pour my grief into lumber and nails, it would swallow me whole. The house where I’d taught Marcus how to throw a baseball in the front yard under a cheap plastic flag banner we’d hung for the Fourth of July. The house where every wall held forty years of photographs and school drawings and quietly repaired heartbreak.

“Helen,” I said carefully, because the sedatives made my words want to slide around, “I need your help. Can you bring me a pen and some paper? And don’t tell Marcus you visited.”

She studied me for a long moment, like she was checking a flight path for error.

“I’ll be back this evening,” she said. “With more than paper.”

That night, the facility was quieter. The overhead lights dimmed to a softer glow, the nurses’ station buzzing more softly as the television volume dropped. I could hear someone down the hallway snoring through the half‑closed door.

Helen slipped into my room the way my granddaughter sneaks past her curfew—eyes bright, shoulders squared, ready for trouble.

“Before you ask,” she said, holding up a slim silver laptop like a trophy, “yes, I know how to use this thing. My grandkids taught me. Don’t you dare talk to me like I’m made of dust.”

“Wouldn’t dream of it,” I said.

She set the laptop on the rolling tray table and opened it. While it booted up, she handed me a spiral notebook and a blue pen. “Start writing down everything you remember,” she said. “Dates, names, anything that seems off. Memory is evidence.” That was my first real hinge point: someone believed me enough to treat my recall like data, not delusion.

I obeyed. I wrote about the dizzy spell two or three weeks earlier—the exact date was already smudged in my mind. I wrote about the way Marcus had insisted I see a Dr. Patterson, not my regular physician, Dr. Shah, who’d been managing my blood pressure for a decade. I wrote about sitting in an exam room with posters about cholesterol on the walls, about a man who’d walked in wearing a white coat with a stitched name I’d never seen before.

I remembered him asking more questions about my living situation than my symptoms. Did I live alone? Did I have family nearby? Had I ever left the stove on? Had I ever gotten lost driving? He’d barely touched his stethoscope to my chest.

There was a prescription. I remembered the yellow paper, the way Marcus tucked it into his wallet, saying, “I’ll get this filled for you, Dad. Don’t worry about it.” After that, my memory went soft at the edges. Had I started taking the pills? Had I felt drowsy? I couldn’t recall getting into an ambulance, or into Marcus’s car, or signing a single document.

“I don’t remember coming here at all,” I told Helen. “One minute I’m watching the evening news in my recliner with that old mug next to me—you know, the chipped blue one with the little American flag on it—and the next thing I know, I’m waking up under someone else’s blanket.”

“That mug you refuse to throw away,” she said. “The one Sandra bought at the base exchange in ‘78.”

“That’s the one,” I said. “If anyone tried to take it, I’d know.”

Helen nodded like that told her everything she needed to know about my mental state.

“All right,” she said, turning the laptop toward me once she’d pulled up the county property records website. “Let’s see what your son has been up to while you’ve been enjoying the fine amenities of Riverside Extended Care.”

My hands shook as I typed my address into the search bar. Riverside County Property Appraiser, Parcel Search. I’d used that site before, years ago, out of curiosity more than anything. A man likes to know what the world thinks his home is worth.

The page loaded. The words swam for a second before snapping into focus.

Owner: Marcus Patterson.

Sale Date: Two weeks ago.

Sale Price: $615,000.

The market value listed on the same screen was $850,000.

My house had been sold for six hundred fifteen thousand dollars. Two hundred thirty‑five thousand dollars below what the county itself said it was worth.

“He sold it,” I whispered. “He sold my house.”

“To who?” Helen asked, leaning in.

“Buyer: Palmer Properties Management LLC,” I read, my voice flat.

Helen sat back. “Is that Vanessa?” she asked.

Marcus had mentioned the name Vanessa in passing over the last few months. Vanessa this, Vanessa that. Full of real estate tips and life advice. I’d heard the smile in his voice when he said it.

“He said she was a real estate agent,” I said slowly. “He never brought her by. Said our schedules never lined up.”

“Real estate,” Helen repeated. “Of course.”

I stared at the screen. “I didn’t sell my house, Helen. I’ve been unconscious or heavily medicated. This is fraud.”

She looked at me carefully, her hazel eyes sharp. “Richard, I have to ask this, and you know why. Are you sure you’re thinking clearly?”

“Test me,” I said immediately. “Ask me anything.”

She did. She asked me to subtract thirteen from one hundred by sevens. She asked me who the vice president was. She asked for the names of the neighbors on our block and which houses they lived in. She asked what year Sandra died.

I answered every question.

When she was satisfied, she blew out a breath. “Then we need to get you out of here and into a lawyer’s office,” she said. “Tomorrow morning, I’m calling my grandson Brad. He’s a patient advocate at County Hospital. This is his wheelhouse.”

For the first time since I woke up under that fluorescent hum, I felt something other than anger and bewilderment. I felt a thin, bright thread of hope.

The next morning, before Helen could arrive, my son did.

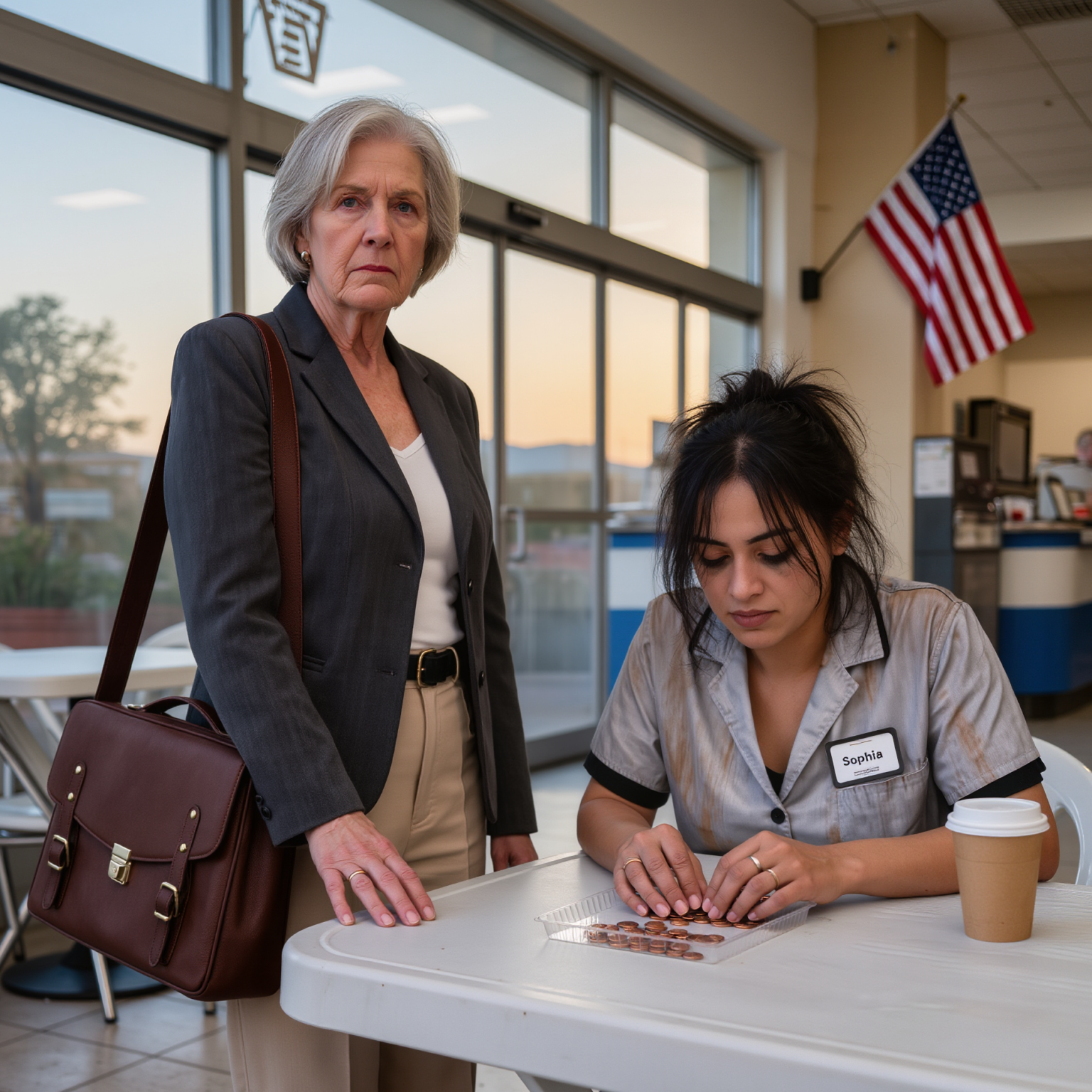

Marcus walked in wearing a navy blazer and a tie I’d given him three Christmases ago, the one with tiny rockets on it. Beside him was a woman I’d never met. She was in her mid‑thirties, with glossy dark hair, a tailored dress, expensive heels, and makeup applied with military precision.

“Dad,” Marcus said, with a brightness that sounded just a little forced. “I wanted you to meet someone. This is Vanessa, my fiancée.”

Fiancée.

He’d mentioned a girlfriend, someone special. He’d never said the word “engaged.”

Vanessa stepped forward with a warm smile and extended her hand. “Mr. Patterson,” she said, her voice smooth as polished marble, “it’s so good to finally meet you. Marcus has told me so much about you. I’m so sorry about your condition.”

“My condition?” I repeated.

“The cognitive decline,” she said gently, glancing at Marcus. “The dementia. It must be frightening.”

“I don’t have dementia,” I said.

“Dad, please,” Marcus cut in, his voice edged with something new—annoyance, or maybe fear.

“Marcus,” I said, ignoring him for the moment, “did you sell my house?”

He stiffened. Vanessa’s hand drifted to his arm in a perfectly choreographed gesture of support.

“Dad,” he began, “I did what I had to do. Your care here costs $8,000 a month. The house was sitting empty. It made financial sense.”

“You had no right,” I said. “That house is mine.”

“Was,” he corrected quietly. “Dad, you signed power of attorney over to me. Remember? Right before the episode?”

I stared at him. “I didn’t sign anything,” I said. “I would remember signing over my life.”

“You were confused,” Vanessa said sweetly. “Dr. Patterson documented everything. The confusion, the memory loss, the paranoid delusions. Patients with early‑stage dementia often don’t recognize their symptoms. It’s very common.” Her eyes were sympathetic, but there was something hard behind them, like steel under velvet.

“What paranoid delusions?” I demanded.

Marcus shifted, looking anywhere but at me. “You called me fifteen times one night,” he said. “You were convinced people were breaking into the house. You called the police on Mr. Jenkins across the street for spying on you. You left the stove on three times in a week.”

“That never happened,” I said. My voice stayed level only because years of defense contracting had taught me that shouting never changed the math.

Vanessa squeezed his arm. “Honey,” she murmured, just loud enough for me to hear, “the doctor said this would happen. Fighting it will only make it harder on him.”

Marcus looked at me then, really looked, for the first time since he walked in. I searched his face for the boy who used to sit at the kitchen table with a Stars and Stripes mug full of hot chocolate, asking me why the moon didn’t fall out of the sky.

All I saw was a man who had convinced himself he was the hero of a story where I was the problem to be solved.

“The power of attorney is with my lawyer,” he said. “Dad, I’m trying to help you. This facility is excellent. You’re safe here. Vanessa and I are getting married next month. We want you there, but you need to focus on getting better.”

“Getting better from an illness I don’t have,” I said.

Vanessa’s smile tightened. “Mr. Patterson,” she said, her tone cooling half a degree, “I know this is difficult. But Marcus is doing what’s best for you. You raised a good man. Trust him.” That was when I realized this wasn’t just about my son’s fear of losing his father. This was about numbers on a screen: $615,000. Two hundred thirty‑five thousand dollars in instant equity. Eight thousand dollars a month in my so‑called “care.”

After they left, the air in my room felt thinner. The sedatives pressed down on my thoughts like a heavy blanket, but underneath that weight, something solid formed.

I wasn’t just going to get out of here.

I was going to take my life back, inch by inch, signature by forged signature.

When Helen arrived that afternoon with her grandson Brad in tow, I told them everything. Brad was in his early thirties, in a rumpled dress shirt and khakis, with a hospital badge clipped to his belt that read PATIENT ADVOCATE. He carried a legal pad and a tired expression that eased when he listened.

“Mr. Patterson,” he said after I finished, “I’m going to arrange for an independent medical evaluation. If everything you’re telling me is accurate—and it lines up with a lot of what I’ve seen—then there’s a strong case here. But first, we need to document your baseline cognitive status, and we need a doctor who doesn’t golf with your son’s lawyer.” Another hinge sentence landed there: if we could prove my mind was intact, the rest of the story would stop sounding like a confused old man’s complaint and start sounding like evidence.

Two days later, a woman with kind eyes and a firm handshake walked into my room with a canvas bag over her shoulder.

“Mr. Patterson? I’m Dr. Patricia Wells,” she said. “I’m a geriatric psychiatrist. Brad asked me to come by. Mind if we talk for a while?”

“Talk away,” I said. “It’s not like I have plans.”

She smiled. “I’ll need a few hours,” she warned. “We’re going to do some memory tests, some problem‑solving, some questions about your mood. Think of it as a very long job interview.”

For three hours, she put my mind through its paces. I drew intersecting pentagons. I repeated lists of words forwards and backwards. I named animals, presidents, and my own grandchildren. I answered questions about the date, the year, the city we were in. I solved word problems that would have made my freshman engineering students sweat.

At the end, she closed her notebook and set her pen down carefully.

“Mr. Patterson,” she said, “you score in the ninety‑fifth percentile for your age group. You have no signs of dementia, no significant cognitive impairment, and no memory loss beyond what we’d expect from someone who has been heavily sedated.”

I swallowed. “Then why am I here?”

“Because,” she said, her voice turning hard, “someone gave you benzodiazepines, probably over several days, and then presented you as confused and incompetent. Someone had you committed to this facility based on false information. That’s medical fraud, and if it’s tied to financial decisions, it’s also elder abuse.”

“Can you help me?” I asked.

“I can testify,” she said. “I can put this evaluation in writing. But you need a lawyer. A good one. Brad says he has a name for you.”

The lawyer arrived that evening.

Thomas Brennan was in his fifties, with gray at his temples and a suit that fit like he’d stopped caring about impressing anyone years ago. His tie was crooked. His eyes, however, were very sharp.

“Mr. Patterson,” he said, shaking my hand. “Tom Brennan. I specialize in elder abuse and financial exploitation cases. Brad and Dr. Wells filled me in, but I want to hear it from you. Start at the dizzy spell and don’t leave anything out.”

I told the story again. By now, it flowed more smoothly. The words had worn grooves in my tongue.

Brennan took notes, occasionally interrupting to clarify a date or a name. He asked about my regular doctor, my relationship with Marcus, my financial situation. When I mentioned the $615,000 sale price, his jaw clenched.

“The appraised value was eight‑hundred fifty, you said?” he confirmed.

“That’s what the county site showed,” I said.

He scribbled something down. “And the buyer is an LLC connected to Vanessa, your son’s fiancée.”

“Palmer Properties Management,” I said. “She’s a real estate agent.”

Brennan sat back, tapping his pen against the pad. “This is more common than you’d think,” he said quietly. “Adult children under financial pressure. A parent with valuable assets. A doctor willing to sign paperwork without doing their job. The facility usually isn’t in on it. They take patients in good faith based on medical documentation. But your son and this Dr. Patterson? They’re in deep.”

“What can we do?” I asked.

“First, we get you released,” Brennan said. “Dr. Wells’s evaluation should be enough to convince the facility’s medical director that you were misdiagnosed. Second, we file an emergency petition in court for a restraining order against Marcus—no access to your remaining assets, no decision‑making authority. Third, we start building a criminal case. Fourth, we go after the house. If the power of attorney was obtained fraudulently, the sale can be unwound.”

“Who bought the house after Palmer Properties?” I asked. My engineer’s brain wanted a clean chain of custody.

“We’ll find out,” he said. “But if I had to bet, I’d say Vanessa used a web of shell companies to make it harder to trace. People like her usually do.”

“People like her?” I asked.

He met my eyes. “Predators,” he said simply.

Within forty‑eight hours, Dr. Wells had submitted her evaluation to the facility’s medical director. To their credit, once faced with hard data and the specter of liability, Riverside Extended Care moved quickly. My chart was updated. My diagnosis was changed. The commitment order was flagged as problematic.

The administrator—Mr. Lewis, a thin man with a permanently worried expression—came to my room with a packet of discharge papers and an apology that sounded practiced but not entirely hollow.

“Mr. Patterson, we had no idea,” he said. “The paperwork we received painted a very different picture of your condition. We relied on the referring physician’s documentation.”

“You relied on lies,” I said. “But I get that you were the last link in the chain, not the first.”

He winced but didn’t argue.

Brennan’s emergency petition for a restraining order was granted faster than I thought possible. A judge I’d never met saw enough red flags in the documentation to freeze Marcus out of my finances pending a full hearing.

That hearing was scheduled three days later in Judge Catherine Morrison’s courtroom, a beige, high‑ceilinged space with a flag standing behind the bench and a carved wooden seal that reminded me of mission patches from my NASA days.

In the meantime, I couldn’t go home. Because legally, on paper, my home wasn’t mine. Helen cleared a guest room for me, tucked between boxes of Christmas decorations and a treadmill that had become a very expensive clothing rack. She put my favorite foods in her pantry, let me take the bedroom with the window that faced my dark, empty house across the fence. Every morning, I could see the outline of my roofline against the sky, the spot where that little plastic flag still flapped on the porch.

“You’ll be back there,” she said when she caught me staring. “We’re not done yet.”

The day of the hearing, I wore the same navy blazer I’d bought for Sandra’s memorial service eleven years earlier. It fit a little tighter around the middle, but it still buttoned. Helen drove. Brennan met us on the courthouse steps, a stack of folders under his arm.

Inside, the air smelled like old paper and recycled air conditioning. Marcus and Vanessa sat on one side of the aisle with their attorney, a slick young man whose suit probably cost more than my first car. Marcus looked pale; Vanessa looked annoyed.

We took the other side. Brennan’s expression was calm, but his eyes were bright. Dr. Wells appeared on a video screen, ready to testify.

Marcus’s lawyer went first. He painted a picture of a devoted son forced into difficult decisions by a father’s decline. He presented Dr. Patterson’s evaluation, full of words like “severe cognitive decline” and “paranoid ideation.” He described supposed incidents at my home—forgotten bills, misplaced keys, imaginary intruders.

He handed up a thick document labeled DURABLE POWER OF ATTORNEY, bearing what looked like my signature.

Then Marcus took the stand.

Under oath, he told the court about my “months of decline.” About how I’d repeated myself in conversations, how I’d gotten lost driving to the grocery store, how I’d left the stove on. He spoke with just the right amount of tremor in his voice, the concerned son barely holding it together. If I hadn’t been there, I might have believed him.

When Brennan stood up for cross‑examination, the temperature in the room seemed to drop a degree.

“Mr. Patterson,” he began, “when exactly did your father sign this power of attorney?”

“September fifteenth,” Marcus said. “At my apartment.”

“So your father drove to your apartment?”

“Yes.”

“Was anyone else present?”

“Vanessa,” Marcus said. “She witnessed it.”

“I see,” Brennan said. “And this fall your father supposedly had—the one that left him so confused—when was that?”

“September twentieth,” Marcus replied.

“Five days later,” Brennan said. “And you immediately arranged for his commitment to Riverside Extended Care?”

“Within a week,” Marcus said. “I wanted to make sure he was safe.”

“Very thoughtful,” Brennan said dryly. “Tell me, when did you sell your father’s house?”

“October first,” Marcus said.

“Two weeks after the fall,” Brennan repeated. “Fast work. Did you list the house on the open market?”

“No,” Marcus said. “We had a buyer.” He shot a quick glance at Vanessa.

“Palmer Properties Management,” Brennan said. “That’s your fiancée’s company, correct?”

Marcus hesitated. “Yes.”

“And what did Palmer Properties pay for the house?” Brennan asked. “Our records show it was appraised at $850,000.”

“Six hundred fifteen thousand,” Marcus said in a small voice.

“So you sold your father’s paid‑off home to your fiancée’s company at a $235,000 discount,” Brennan said. “To pay for care that, at $8,000 a month, you hadn’t even incurred yet.”

“I needed to sell quickly,” Marcus said. “To make sure—”

“To make sure Vanessa’s company got a very good deal?” Brennan cut in.

Vanessa’s lawyer objected. The judge sustained the objection but made a note.

Then it was our turn.

Dr. Wells’s face appeared on the screen, calm and composed.

“In your professional opinion, Dr. Wells,” Brennan asked, “does Richard Patterson require full‑time care in a nursing facility?”

“Absolutely not,” she said. “Mr. Patterson is cognitively sound, physically stable, and fully capable of independent living. There is no medical basis for a diagnosis of dementia. The only abnormality in his labs is the presence of benzodiazepines, which were not prescribed by me or his regular physician.”

“And if someone were to administer such medications without properly informing the patient?” Brennan asked.

“It would impair their cognition and could make them appear confused and disoriented,” she said. “It would also be a serious breach of medical ethics.”

Marcus’s lawyer called Dr. Patterson to rebut. The man who’d briefly examined me walked to the stand, his collar damp with sweat.

Under questioning, he admitted he’d seen me once for maybe fifteen minutes. He admitted he had not performed standardized cognitive testing. He admitted he had based his dementia diagnosis primarily on Marcus’s report of my behavior.

Under Brennan’s cross‑examination, he admitted he had been paid $5,000 in cash by Marcus two days before signing the commitment papers.

By the time he stepped down, he looked smaller.

Judge Morrison removed her glasses and looked from one table to the other.

“I’ve heard enough,” she said. “The court finds that the durable power of attorney was obtained under false pretenses and is therefore invalid. The commitment to Riverside Extended Care was based on fraudulent medical documentation. The sale of Mr. Patterson’s home is hereby referred to the district attorney’s office for criminal investigation. In the meantime, I am issuing a restraining order prohibiting Marcus Patterson and Vanessa Palmer from contacting Richard Patterson or accessing any of his assets. Mr. Patterson, you will need to pursue recovery of your home through civil litigation. I am also ordering a freeze on the assets of Palmer Properties Management pending further review.”

Marcus stood up, his face drained. “Your Honor, I’m his son,” he said. “I was trying to help.”

“You were trying to steal from him,” Judge Morrison said coolly. “Sit down, Mr. Patterson.” That was the hinge where everything tilted. Up to that sentence, I’d been on defense. After it, the system itself started turning toward me instead of against me.

Outside the courtroom, Vanessa grabbed Marcus’s arm hard enough that he flinched.

“This is your fault,” she hissed. “You said he wouldn’t fight back. You said he was confused. You said it would be easy. You said once we had the house, he couldn’t do anything.”

They both realized I was standing a few feet away, listening.

Vanessa’s expression smoothed over like ice reforming. “You’ll never get that house back,” she said to me. “I’ll drag this through court for years. By the time you’re gone, you’ll have spent more on legal fees than the place is worth.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But you’ll spend just as much defending yourself against criminal charges. And I’ve got more time left than you think.”

The district attorney assigned to my case was a woman named Caroline Chen. She was in her forties, with a no‑nonsense bob and a reputation for coming down hard on anyone who used age as a weapon.

“I hate these cases,” she told me in our first meeting. “Not because I don’t want them, but because they keep happening. People think they can write their parents off as if they’re broken appliances and take whatever they want. We’re going to make an example of this.”

Within two weeks, she had enough to file charges.

Marcus was charged with elder abuse, fraud, and conspiracy to commit fraud. Dr. Patterson was charged with medical fraud, conspiracy, and accepting bribes. Vanessa was charged with conspiracy to commit fraud, theft by deception, and multiple counts of real estate fraud.

Marcus called me from his lawyer’s office before he turned himself in.

“Dad,” he said, his voice raw, “please don’t do this. I’m your son.”

“Then act like it,” I said. “Sons don’t drug their fathers and sell their homes for a discount.”

“Vanessa said—” he began.

“I don’t care what Vanessa said,” I interrupted. “You’re the one who handed her the keys. You’re the one who signed the checks.”

“I thought…” he faltered. “I thought you didn’t really want that house anymore. You always said it was too big. I thought we could use the money to start our life, and you’d be taken care of. I thought it would all be ours eventually anyway.”

“Eventually,” I said, “after I’m gone. Not while I’m still drinking coffee out of a chipped mug and arguing with Helen about whose turn it is to take the trash to the curb.” I could picture that mug in my hand, the little flag on its side, and it grounded me more than any therapist’s breathing exercise ever could.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’ll do anything. Just drop the charges.”

“Can you give me back the six weeks you stole from me?” I asked. “Can you give me back the dignity of waking up in my own bed instead of under fluorescent lights? Can you give me back my sense of safety when my only son walks into a room?”

He was silent.

“No,” I said. “You can’t. So we’re going to let this play out. Maybe it’ll teach you something a lecture never could.”

Vanessa called me five minutes later from Marcus’s phone.

“Mr. Patterson,” she said smoothly, “let’s talk like reasonable adults. Marcus is very upset. He loves you. He was trying to protect you.”

“By selling my house to his fiancée’s LLC for $615,000?” I asked. “At a quarter of a million under value?”

“By securing your future,” she corrected. “Look, the sale is done. Fighting this will only drain your finances. The court will see Marcus acted in good faith.” Her voice cooled. “You’re an older gentleman, Mr. Patterson. You had a dizzy spell. You could have a stroke tomorrow. Who’s going to believe you didn’t need help? We have documentation from a licensed physician.”

“A physician you paid in cash,” I said. “Be careful, Ms. Palmer. Extortion isn’t a good look for someone under investigation.”

“You can’t prove anything,” she said.

“Watch me,” I replied, and hung up.

The criminal case moved faster than the civil one. Dr. Patterson, faced with financial records and the threat of prison, took a plea deal. He admitted to accepting payment in exchange for signing commitment papers based on exaggerated or false information. He agreed to testify against Marcus and Vanessa.

In court, I had to tell my story again, this time to a jury of twelve strangers.

I described waking up under that cracked ceiling, the faded flag picture on the wall, the flip phone that wasn’t mine. I talked about the pills, the fog, the way the world had suddenly decided I was broken. I talked about the property records page, that ugly little line that said Owner: Marcus Patterson and the number $615,000 that had turned my life into a balance sheet.

Marcus’s attorney tried to poke holes in my memory. Was I sure about the dates? Was I sure I hadn’t agreed to any of this? Was I sure I hadn’t left the stove on? Hadn’t gotten confused once or twice?

“Of course I’ve gotten confused once or twice,” I said. “I’m human. But confusion is not consent. Forgetting what day it is every now and then doesn’t mean my son gets to empty my house and rewrite my life.”

The jury listened. Some of them were closer to my age than to Marcus’s. A few nodded.

Dr. Wells testified again. So did Brad. So did Helen, who nearly vibrated out of the witness chair with righteous fury as she described the moving trucks and Marcus’s calm lies.

Vanessa’s past came out too. Brennan and the DA had dug deep. Two years earlier, in another state, she’d befriended an elderly widow with a paid‑off condo near the beach. She’d “helped” the woman sign a power of attorney, sold the condo through an LLC, and walked away with most of the money. The woman’s family had sued, but Vanessa settled quickly and skipped town.

“It’s a pattern,” the DA told the jury in closing arguments. “She targets families where there’s some distance, some guilt, some financial pressure. She offers an easy answer. And then she walks away with everything while the family tears itself apart. This time, thanks to Mr. Patterson and the people who believed him, she didn’t get away with it.”

Marcus, facing the evidence and Dr. Patterson’s testimony, took a plea deal of his own. He pled guilty to elder abuse and fraud in exchange for a reduced sentence and his cooperation against Vanessa.

He got two years in prison and five years of probation. He lost his CPA license. He agreed to never again accept power of attorney from any family member.

Before sentencing, he asked to speak to me.

We met in a conference room at the courthouse with Brennan sitting quietly in the corner. Marcus looked thinner, as if the weight of what he’d done had finally settled onto his shoulders.

“Dad,” he said, “I know sorry doesn’t cut it. But I am sorry. Vanessa made it sound so reasonable. She kept saying I was protecting you, that it was better to do it now than wait for something worse to happen. I didn’t see it as stealing. I saw it as… rearranging.”

“Rearranging my life without asking,” I said.

“I was going to give you part of the money,” he said desperately. “Once we got settled, once the wedding was paid for, once… I wasn’t trying to cut you out completely.”

“You put me in a nursing home I didn’t need,” I said. “You took my keys, my phone, my independence. You emptied my house. You turned my memories into line items. And you think offering to give me a slice of what was already mine will fix that?”

He swallowed hard. “I know I messed up. I know. But I’m still your son. I’m the only family you have left. If I do my time, if I testify against Vanessa, can we… can we rebuild?”

I thought of that little flag mug in my cupboard, the one thing I’d asked Helen to retrieve from the box of odds and ends the movers hadn’t touched. I thought of all the mornings Marcus had sat at my table, swinging his feet, asking how satellites stayed up.

“Marcus,” I said quietly, “I love you. I will always love you. That’s not something prison or court orders can touch. But I don’t trust you. Not yet. Maybe not for a long time. Love doesn’t erase what you did. It just makes it hurt more.”

“So that’s it?” he asked. “You’re done with me?”

“For now,” I said. “You need to live with the consequences of your choices. I need to live in peace. Someday, maybe, we’ll find a way to talk again without a lawyer in the room. But that day isn’t today.”

He cried then. Real tears. I believed his remorse. I also believed in locks and boundaries.

Vanessa went to trial.

She pled not guilty. Her lawyer painted her as a hardworking professional who had no idea Marcus’s actions were fraudulent. She was just the fiancée, they said, caught in the crossfire of a family dispute.

The evidence didn’t agree.

There were text messages: Once he’s in the facility, we can move fast. Make sure your dad signs before he realizes what’s happening. Doctor P wants cash—no paper trail. There were bank records showing money flowing from Marcus to her accounts and from her accounts to shell companies that conveniently owned properties that matched my description.

There was the Arizona widow, flown in to testify, her voice shaking but strong as she described how Vanessa had taken her to “sign some papers for insurance” and how she’d woken up one morning to find strangers moving furniture out of her condo.

The jury deliberated for three hours.

They came back with guilty on every count.

Vanessa was sentenced to five years in prison, with additional conditions that made it unlikely she’d ever hold a real estate license again.

When the judge read the sentence, she turned and looked at me. Her eyes were cold, assessing. Even in handcuffs, I could see her mind working, cataloging, recalculating. Some people don’t break. They just redirect. Maybe prison would slow her down. Maybe it wouldn’t. But at least, for a while, she wouldn’t be meeting anyone’s lonely father for coffee and “advice.”

The civil suit to unwind the house sale took longer. Lawyers sent letters. LLCs produced documents. Brennan followed the money from Palmer Properties to a second company to a third. In the end, every trail led back to Vanessa.

Eventually, faced with more legal fees than profit, her attorneys advised settlement.

Palmer Properties Management transferred the house back to me. They also paid $200,000 in damages. The court ordered Marcus to reimburse me for another portion of the losses over time.

Eight months after I woke up under that cracked ceiling, I walked back through my own front door.

The house was empty.

No furniture. No framed photos on the walls. No boxes of Christmas ornaments in the hall closet. The indentation where my recliner had sat for twenty years was a darker patch on the carpet.

But the walls I had raised board by board were still standing. The windows I’d installed were still there, streaked with dust but intact. The kitchen where Sandra and I used to drink coffee out of matching flag mugs on Sunday mornings still caught the same morning light.

Helen helped me rebuild. We went to estate sales and thrift stores. We bought a secondhand couch that sagged a little in the middle but felt right. We found a dining table with a scratch down the center that looked like character, not damage.

I put my old flag mug—the one she’d saved for me—on the kitchen counter. It had a new chip now, a little flaw near the handle. It suited me.

“You could buy all new things,” Helen pointed out one afternoon as we unloaded a box of mismatched plates.

“I don’t want all new,” I said. “I want things with a past that survived anyway.” That was my last hinge: realizing that survival alone wasn’t the end, that I got to choose how to live the chapter after.

People asked me, in the months that followed, if I’d done the right thing. If I should have been more forgiving. If I should have shown more mercy to my only son.

“Loving someone doesn’t mean letting them hurt you without consequence,” I would say. “Being family doesn’t give you a free pass to treat a person like a broken thing.”

Marcus served his two years. He’s out now, on probation. Six months ago, he sent me a letter asking if we could meet “for coffee, maybe at the kitchen table.” He said he’d been in therapy. He said he understood more now about why what he’d done was wrong.

The letter sits in a drawer by my bed. Some nights I take it out and read it. Some nights I don’t. I haven’t answered yet.

Maybe someday I will. Maybe someday I’ll be ready to hear what he has to say without hearing, underneath every word, the scrape of a moving truck loading my life into the back.

But right now, I’m busy.

I’m seventy‑six years old. I have my house. I have Helen next door, who checks on me and brings over iced tea in the summer and argues with me about politics on her porch under a little flag magnet stuck to her screen door. I have a backyard where the jasmine still blooms and the neighborhood kids still cut through on their bikes like it’s a shortcut through time.

Most importantly, I have my dignity.

I’m the man who refused to be a side character in the story of his own life. I’m the man who heard the world tell him he was confused and decided to trust his own mind instead. I’m the man who took a number—$615,000—and turned it from the price of his stolen life back into just a line on a page.

If you’re reading this and something about my story feels uncomfortably familiar, if a relative is “helping” with your bills a little too eagerly, if someone keeps telling you you’re forgetful when you know you’re just tired, if papers appear in front of you that you don’t fully understand—listen to that unease.

You have rights. You have options. You have worth.

You are not a burden simply because you’ve collected more birthdays than the person talking down to you. Your signature still matters. Your voice still matters. Your consent still matters.

Get a second opinion. Call a friend who will tell you the truth even when it’s messy. Reach out to a patient advocate, a legal aid clinic, a local agency on aging. Document things. Dates. Names. Amounts. Keep your own notebook, even if your hands shake a little when you write.

And if the person trying to take control of your life shares your last name?

Remember this: family is not a shield that makes harm harmless. Blood is not a blank check. Sometimes the most loving thing you can do—for yourself and for the people who come after you—is to set a boundary and enforce it, even when it breaks your heart.

My name is Richard Patterson. I’m a retired engineer, a widower, a neighbor, a man who still drinks coffee out of a chipped mug with a tiny American flag on it.

But after everything that happened, I became something else, too—though it took me a while to say the words out loud.

About a month after Vanessa was sentenced, Helen marched into my kitchen one Tuesday morning with a grocery bag, a stack of papers, and that look on her face that meant my day was about to get complicated.

“You’re coming with me,” she announced, unloading eggs and a loaf of bread like a woman stocking a bomb shelter.

“Good morning to you too,” I said, pouring coffee. “Going where?”

“Senior center downtown,” she replied. “There’s a workshop on financial safety and power of attorney. Brad’s speaking. So is some lady from Adult Protective Services. I already signed you up to talk.”

I choked on my coffee. “You did what?”

“Relax,” she said, waving a hand. “Ten minutes. You tell your story, they hand out pamphlets, everyone eats cookies. It’ll be good for you. And for them.” She softened. “There are a lot of people who don’t get as far as you did, Richard. They need to see somebody who fought back and actually won something.”

My first instinct was to refuse. I’d spent my career speaking in conference rooms and briefings with charts behind me and acronyms on every slide. This was different. This was my life, not thrust calculations.

“I don’t want to be a poster child,” I muttered.

“Too late,” she said. “You already are, whether you like it or not. Might as well make sure the poster has the right words on it.”

She had a point. She usually did.

Two hours later, I found myself in a beige multipurpose room that smelled like coffee, copier toner, and floor polish. An American flag hung in the corner, slightly crooked. A homemade banner taped to the wall read: KNOW YOUR RIGHTS: PROTECTING YOURSELF AS YOU AGE.

About thirty people sat in folding chairs—mostly gray hair, a few younger faces who looked like adult children dragged along for moral support. Brad stood at the front, flipping through slides on a small projector: COMMON SCAMS, RED FLAGS, LEGAL TERMS.

He spotted me and smiled. “Our guest of honor,” he said quietly when I approached. “You okay speaking for a few minutes?”

“You know, everyone keeps asking me that lately,” I said. “No one used to ask if I was okay. I must be giving off fragile vibes.”

“You’re giving off survivor vibes,” he said. “Big difference.”

I didn’t feel like either when he handed me the wireless microphone, but once I started talking, the words came easier than I expected.

I told them the short version. Waking up in the facility. The missing phone. The property records site with that ugly $615,000 number staring back at me. The pills. The lies. The way everyone around me kept insisting I was confused when I knew I wasn’t.

I watched people’s faces as I spoke. Some looked horrified. Some looked hollow, like I was describing something they’d seen up close. A woman in the second row dabbed at her eyes with a crumpled tissue. A man in the back clenched his jaw so hard I could see the muscles jumping.

“The worst part wasn’t the money,” I told them. “Don’t get me wrong—that mattered. I spent my whole life building that safety net. But the part that kept me up at night was this: my son looked me in the eye and decided his version of my life mattered more than mine. He decided that because I’d had a dizzy spell and turned sixty‑five, my consent was optional.”

I took a breath, feeling the weight of the room listening.

“If there’s one thing I want you to take from my story,” I said, “it’s this: if your gut is telling you something’s off, listen to it. Get another opinion—from a doctor who isn’t in anyone’s pocket, from a lawyer who doesn’t share a last name with the person pushing papers in front of you, from a neighbor who’s seen you hunt for your keys enough times to know what’s normal and what isn’t. Confusion does not equal surrender. Getting older does not make you public property.”

Afterward, people lined up to talk to me. They told me about daughters who had “borrowed” money that never got paid back, about nephews who had moved in “to help” and then slowly taken over, about caregivers who had started out kind and ended up cruel.

A retired teacher pressed a folded piece of paper into my hand. It was a list of account numbers another relative had pressured her to add them to. “Do you think I should call a lawyer?” she whispered.

“Yes,” I said. “Today. And tell them everything.”

When we got home, Helen made grilled cheese sandwiches in my half‑furnished kitchen while I sat at the table and stared at the list of resources Brad had handed out. Hotlines. Legal aid offices. Support groups. Words I’d never paid much attention to when I saw them on bulletin boards before.

“You did good,” she said, sliding a plate toward me.

“Felt like I talked too much,” I said.

“You? Never,” she snorted. Then she grew serious. “You know, when Marcus told me you’d had a stroke, I believed him. I didn’t check. I didn’t push. I thought I was being respectful.”

“You came anyway,” I said. “That’s what matters.”

“I almost didn’t,” she admitted. “I almost stayed in my lane, like everyone says we’re supposed to. I keep thinking—if I hadn’t shown up when I did, how long would it have taken before anybody realized something was wrong?”

“Longer,” I said. “Maybe too long. But you did show up.” I looked at her. “You were my second opinion when the world was trying to convince me I was broken.”

Her eyes went shiny. She blinked hard and changed the subject by complaining about Brad’s driving on the way home.

Word of what had happened to me spread, the way things do in neighborhoods and church halls and barber shops.

Some people avoided me. It wasn’t unkindness, exactly. It was a sort of flinching. Like I was walking around with a visible crack, and looking at it too closely might make them notice their own. Others were overly sympathetic, treating me like a tragic figure instead of a man who still had to take out his trash on Tuesdays.

Then there were people like Mr. Jenkins across the street—the same poor guy Marcus had claimed I’d called the cops on.

One afternoon, as I was wrestling a new mailbox into the post (the old one had been bent during the movers’ enthusiastic exit), he walked over with a small box in his hands.

“Thought this might be yours,” he said, holding it out.

Inside was my old Stars and Stripes mug, carefully wrapped in newspaper. I hadn’t even realized it hadn’t come back from Helen’s emergency rescue mission.

“Found it in a box in the garage,” he said. “Marcus asked me to hold some stuff for him when they were loading the truck. Forgot about it until I saw the news about the trial on TV.” He cleared his throat. “I didn’t know what was really happening, Richard. If I had…”

“I know,” I said. “Most people didn’t. That’s how they got as far as they did.”

He nodded, looking relieved I wasn’t going to bite his head off. “If you ever need someone to look over your yard when you’re out, just say so,” he added. “I’m home a lot now that the knees don’t like stairs.”

“I might take you up on that,” I said.

Later, I set the mug in its old spot on the counter. The little flag on the side was more scratched than I remembered. The glaze was starting to fade near the rim. It wasn’t pretty by any objective standard, but it was mine, and it had survived. I ran my thumb over the tiny flag and felt something in my chest settle.

Over the next year, my life slowly reshaped itself.

I fixed the sagging step on the front porch. I planted tomatoes in the raised bed out back. I had dinner with Helen twice a week, alternating whose kitchen we cluttered. I went back to my old church, where the pastor slipped an extra line into a sermon one Sunday about honoring your elders with integrity, and a few heads bowed more sharply than usual.

I kept speaking, too. Not a lot—my energy wasn’t what it had been when I was pulling seventy‑hour weeks on satellite projects. But once a month or so, I’d show up at a community center, or a library, or a church basement, and tell the story again. Sometimes Brad introduced me. Sometimes someone from Legal Aid did. Sometimes it was just a social worker with a box of donuts and a coffee urn.

Every time, there was at least one person who waited until the room had mostly emptied, then came up to me with a look I recognized now.

“My daughter says I don’t remember things right anymore,” one woman said. “But I remember every bill I’ve ever paid.”

“My grandson keeps bringing over forms from the bank for me to sign,” an older man told me. “He says it’s just to make things easier. I keep pretending I lost my glasses.”

“My brother put Mom in a place like the one they stuck you in,” a middle‑aged woman said, clutching her tote bag like a life preserver. “He says she’s better off there, but she keeps calling me crying. I didn’t know this kind of thing had a name.”

“It has several,” I said. “But the important one is: wrong.”

Sometimes I went home after those talks feeling drained, the way you do after a funeral. Sometimes I felt oddly energized, like I’d just tightened a loose bolt on something that mattered.

One afternoon, about two years after the trial, I got a letter in the mail with a return address that made my stomach flip.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Marcus.

I took the envelope inside, set it on the table next to my flag mug, and stared at it for a while. The house was quiet. Helen was out grocery shopping. The clock over the stove ticked.

Eventually, I opened it.

His handwriting hadn’t changed since high school—still a little messy, still too many loops on the y’s.

He wrote about prison. About the classes they made him take on ethics and responsibility. About the guys he’d met who’d grown up with nothing and stolen out of desperation, not entitlement. About the counselor who’d told him, “The problem with you white‑collar types is you always think you’re the hero, even when you’re writing yourself as the villain.”

He wrote about Vanessa, briefly. How she’d tried to contact him through friends, how he’d decided not to respond. “I’m not writing this to make you feel sorry for me,” he said. “I did what I did. I’m here because of my choices. But for the first time, I can see how I made them. I let someone else’s voice drown out yours in my head. That’s on me.”

He ended with a question.

Would I ever be willing to see him?

I didn’t answer right away. I put the letter in the same drawer where I kept my passport, my Social Security card, and the original deed to the house—the one with my name still cleanly printed on it.

Weeks went by. The tomatoes ripened and then withered. The holidays came and went. Helen bullied me into putting a wreath on the door. I made my granddaughter roll her eyes by mailing her a birthday card with a check and a note that said, “Spend this on something impractical before you’re old enough for people to try to manage your life.”

Every so often, I’d take the letter out and read it again. My anger pulsed differently now. Less like an open flame, more like a banked coal.

One evening, as the sun slid down behind the roofs across the street and painted the sky that particular California orange you don’t appreciate until you’ve almost lost it, Helen knocked on my back door and let herself in.

“You’re thinking too loudly,” she said, putting a casserole on the counter.

“Didn’t say a word,” I protested.

“You didn’t have to,” she replied. “You get this line between your eyebrows when you’re stuck in a mental loop.”

I glanced at the drawer where Marcus’s letter lived.

“He wrote again,” I admitted.

“And?”

“Same question,” I said. “Wants to meet. Says he’s out now. Has a job with some nonprofit that helps people reenter after prison. Claims he’s doing the work.”

“You believe him?” she asked.

“Mostly,” I said. “But belief and trust aren’t the same.”

She nodded. “So what’s the question, really?”

I stared at the mug in my hands, thumb tracing the worn flag.

“The question is,” I said slowly, “if I open that door even a crack, do I lose the ground I fought so hard to stand on? Does forgiving him mean I’m saying what he did wasn’t that bad?”

Helen was quiet for a moment.

“You know I love a good grudge,” she said finally. “But I don’t think forgiveness is about saying it wasn’t bad. I think it’s about deciding what you want to carry. You held him accountable. The courts did their part. The house is yours again. The question now is, do you want your life to be about what he did or about what you do next?”

“Easy for you to say,” I muttered.

“Not as easy as you think,” she replied. “Remember my sister? The one who only calls when she needs money? I told her no last month for the first time in my life. She hung up on me. I’m still shaking.”

“Proud of you,” I said.

“Point is,” she continued, “you can forgive without forgetting. You can meet him in a public place, keep your wallet in your front pocket, and still mean it when you say, ‘You hurt me and that doesn’t just vanish.’ Boundaries don’t dissolve because you have coffee.”

I thought about that for a long time.

A week later, I wrote Marcus back.

I told him we could meet. Once. In daylight. At a diner halfway between our cities with a parking lot full of people and a security camera over the door. I told him if he raised his voice, or tried to make me feel guilty for protecting myself, I’d walk out.

He agreed.

The day of the meeting, I almost didn’t go. My hands shook so much I had to set my coffee mug down twice while I tied my shoes. Helen drove me, on the condition that she sit in a booth on the other side of the restaurant “like a secret service agent with better hair.”

When we walked in, Marcus was already there, sitting in a corner booth, fingers wrapped around a glass of water like he was hanging on.

He stood when he saw me. He looked older. Not just in the gray at his temples, but in the way he held himself. Less puffed up. Less certain.

“Dad,” he said.

“Marcus,” I replied.

We sat. The waitress took our orders—two coffees, one slice of apple pie that neither of us ended up touching.

He told me about the reentry program he worked for now, helping people find jobs after prison. He told me about the guys who called him “college boy” at first and then started asking him to help with forms. He told me about the nights he spent replaying the look on my face in that nursing home.

“I thought I was being pragmatic,” he said quietly. “You know? Efficient. You always taught me to look at the numbers, at the systems. I looked at your house and I saw equity. I looked at the facility brochure and I saw safety. I told myself stories that made it all make sense.”

“And when I said no?” I asked.

“I decided you were the one who didn’t understand,” he admitted. “That’s the part that haunts me. Not just what I did, but how easy it was to believe the version where I was noble and you were stubborn.”

We sat with that for a while.

“I’m not asking you to forget,” he said finally. “Or to leave me anything in your will, or any of that. I just… I’d like a chance to show you who I am when I’m not trying to impress the wrong person.”

I watched him, this man who had once been a boy in my backyard waving a sparkler under the July sky, making shapes in the dark while a flag hung limp above the porch.

“I don’t know what our relationship will look like,” I said honestly. “I can’t promise holiday dinners or automatic trust. But I can promise this: I’ll tell you the truth about how I’m feeling. I won’t pretend it’s all fine when it isn’t. If you want a second chance, it’s going to be built on honesty, not on stories we tell ourselves to avoid discomfort.”

“I can live with that,” he said.

We didn’t hug when we left. We shook hands, awkwardly, like two men who’d just signed a difficult truce. Helen pretended not to watch from her booth, but I saw the way her shoulders relaxed when I walked back to her in one piece.

On the drive home, the sky was streaked with contrails, white lines crisscrossing the blue like someone had scribbled on the atmosphere. I watched them fade and thought about all the paths we chart that look straight on paper and end up crooked in real life.

“How do you feel?” Helen asked.

“Tired,” I said. “Lighter. Both.”

“Sounds about right,” she replied.

Life didn’t turn into a greeting card after that. Marcus and I talk sometimes now—short phone calls, occasional emails. He came by the house once, months later, and stood on the porch like a visitor. I didn’t invite him in that time. Maybe I will someday. Maybe I won’t. The point is, the choice is mine.

That’s the part I keep coming back to.

People like Vanessa, like the version of Marcus I met in that nursing home, count on us forgetting that we have choices. They count on us being so grateful for any attention at all that we sign whatever’s put in front of us. They count on us believing the lie that getting older means giving up the right to say no.

I’m not interested in living by that script anymore.

So yes, I’m a retired engineer. A widower. A neighbor who grumbles about trash pickup and worries about property taxes. I’m a man who still wakes up some nights with the phantom smell of antiseptic in his nose and has to remind himself that the ceiling above him is his own.

I’m also a man who learned, later than he’d like but not too late, that protecting yourself is not selfish. That asking questions is not disrespectful. That saying “I don’t agree” to your own child does not make you a bad parent.

And I am not a victim.

I am a survivor, a witness, a warning, and—on good days—a resource.

If you’re in a situation that feels wrong, if someone is tugging at the edges of your independence under the banner of “help,” if you feel that quiet, persistent alarm in your chest, listen to it.

Talk to someone who will really hear you. Call a hotline. Talk to a lawyer. Tell a neighbor like Helen, the one who notices when your porch light stops coming on at its usual time.

You are not being ungrateful. You are not being paranoid. You are not being difficult.

You are being prudent.

My name is Richard Patterson. I’m a seventy‑six‑year‑old man with a chipped mug, a reclaimed house, a stubborn neighbor, and a life that is still mine.

And I am not a victim.

Neither are you.