🔥💔 I TURNED AROUND FOR SECONDS… AND MY DAUGHTER WAS GONE FOREVER 💔🔥

I still remember the sound of the gravel under our shoes that day.

The tiny crunch with every step, the smell of barbecue sauce in the air, the way the wind came off the lake just cool enough to make me pull my jacket a little closer.

It was the kind of afternoon where nothing bad is supposed to happen.

We had driven to Kingston for a simple weekend visit. Just friends, kids, a quiet lakeside town where everyone knew everyone, and the loudest thing you usually heard was a lawnmower or a dog. The kind of place where doors stayed unlocked and mothers relaxed… just a little too much.

My little girl, two and a half, wore her pink jacket—the one she insisted on even when it wasn’t that cold. Her tiny blue shoes kicked at the gravel as she followed her older brother around the front yard. They wandered a bit up and down the driveway slope, then back toward us, then to the fence, then back again.

A small circle of safety.

A routine of back and forth.

A bubble I truly believed she could never slip out of.

I can still see it like a paused movie scene.

The house sitting on its slightly raised section, the open yard, the low fence, the wide view of the road and the lake beyond. No trees hiding sightlines. No sheds. No dark corners. Just open space and ordinary life.

If someone had shown me a picture of that scene and asked, “Can a child disappear from here in seconds?” I would have laughed.

How wrong I was.

One of our friends, Belinda, was leaving. She got into her car, reversed down the driveway. As she passed, she saw my daughter standing on the slope, watching the car. Upright. Stable. Calm. No tears. No fear. Just that serious little face she made when she was concentrating on something.

It was the last confirmed sighting of my child.

I didn’t know that at the time, of course. How could I?

I didn’t feel the world shift or a warning voice in my head. Nothing in me screamed, “THIS IS IT. PAY ATTENTION.”

If anything, I was thinking about sausages and salads, about who liked what sauce, about whether I had packed enough clothes for the kids.

We moved in and out of the house, carrying plates, checking on the baby, laughing about nothing. The boys ran around. My girl, I assumed, ran after them. She had been in the same spot all afternoon—driveway, fence, lawn, driveway, fence, lawn.

If you’d asked any of us adults, we would have sworn someone always had an eye on her.

That was our first mistake.

We didn’t say it out loud, but we all thought: “Someone’s watching. Someone’s got her.”

Later, when we compared stories, we realized the truth:

No one did.

At some point, as the afternoon light started to soften, someone called the kids in for the barbecue. It was a casual call, the kind every parent knows:

“Alright you two, time to come in!”

I expected the usual: heavy toddler steps, the slight delay, maybe a protest. Her brother appeared. She didn’t.

It didn’t alarm me at first. Toddlers are stubborn. They hide behind bushes and fences, convinced they’re invisible. They sit down to play with rocks like they’re diamonds. They wander a few meters away and make you work for your authority.

“Come on, where are you, cheeky girl?” I called again.

No answer.

One of the adults walked down toward the driveway, expecting to see her near the slope where Belinda had just seen her. When she wasn’t there, they checked the fence line where she had been going back and forth all day.

Nothing.

Someone else checked behind the parked cars.

Nothing.

We still weren’t panicking. We were moving fast, but we were in that stage where you’re more annoyed than afraid.

“Honestly, where has she toddled off to now?”

I went inside, calling her name.

Bedroom. Bathroom. Hallway. Behind doors. Under beds. Behind curtains. The kitchen where she had been earlier. The living room where her toys were.

Empty. All of it.

That’s when something cold slid down my spine.

I walked back outside and looked at the others, and I saw my fear reflected back at me. We did that thing where everyone talks at once:

“Have you seen her?”

“I thought she was with you.”

“No, I thought she was with him.”

“I just saw her a minute ago.”

“No, it’s been longer than that.”

The truth settled over us like a heavy blanket:

For a small but unknown amount of time…

no one knew where my daughter was.

We spread out more deliberately now.

The front yard was combed again.

The gap by the fence.

The little dip by the roadside.

The area where grass met gravel.

I remember calling her name louder, my voice beginning to crack. I remember trying to keep my tone “normal” so I wouldn’t scare the other kids. I remember, even in that moment, being half-mother, half-search-party.

But she still didn’t answer.

We went to the back of the house, even though no one had seen her head that way. The yard there was small, fenced, empty. Still nothing.

Someone checked the road.

No child. No car. No one walking by.

The lakefront.

No footprints. No little jacket. Nothing disturbed.

My heart was pounding in a way I’d never felt before. Not like running or excitement. This was something else—a steady, growing drumbeat of horror.

We knocked on neighbors’ doors.

“Have you seen a little girl? Pink jacket, blue shoes?”

Every answer was the same: “No. Sorry. No.”

Kingston is small. People notice things. A child walking alone along the road would have been seen. Yet no one had seen her.

The more people said no, the louder the question became:

Where is she?

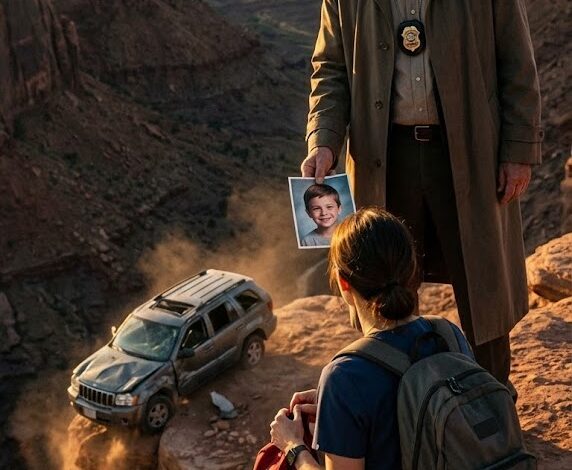

At some point—it’s a blur now—someone called the police. I don’t even remember who. I just remember that suddenly there were uniforms, cars, radios, questions.

They asked us to go through the whole afternoon.

Who arrived when.

What had we been doing.

Who saw her last.

Exactly where had she been standing.

What direction was she facing.

How long had passed.

Time, which had been moving too fast, suddenly slowed into interrogation-speed. Every minute had to be accounted for. Every action, every movement, every assumption.

I answered as best I could, but guilt was already eating me alive.

“If I had been watching closer—

If I hadn’t gone inside—

If I had questioned the silence sooner—”

The officers checked the house again, this time like professionals instead of parents. Under furniture, in cupboards, under the house, in any tiny space a child could crawl into.

Still nothing.

When the sun started to drop, the search grew.

More neighbors joined.

Volunteers appeared.

The police organized grid patterns.

Lines of people walked the land around the house, shoulder to shoulder, eyes scanning every inch of grass and gravel and shoreline. If my daughter had been lying down, curled up, hidden by grass, someone should have seen her.

They saw nothing.

Dogs were brought in, trained to follow scent. They were given her clothes, her toys, her blankets—the smell of her little life. They moved along the driveway, the yard, the road, the lakeside.

No clear trail. No direction. No place where the dogs suddenly pulled or barked or refused to move.

Just… confusion.

The lake was searched. Torches sliced through the dark, hitting the water, the stones, the bank. Divers went in, first near the shore, then further out. Boats moved slowly, carefully. Poles tested the shallows. Later, sonar would be used to scan deeper.

Still, there was no sign of a small body, no pink fabric drifting, no shoe, no scrap, no nothing.

Do you know what it does to a mother’s mind to hear “nothing” over and over again?

I wanted them to find her alive. Of course I did. I still do.

But as the hours turned into a long, cold night, another part of me—small, ashamed, desperate—began whispering:

“Just find something. Please. Anything. Give me a place to grieve.”

Morning came.

Searches widened.

Helicopters flew above the town, tracing the lake edge and surrounding fields. From up there, the property looked even smaller, even more impossible to disappear from.

Officers checked farms, sheds, empty sections, culverts, drains.

Roads leading in and out of Kingston were monitored, then re-checked.

Drivers were stopped and questioned.

Local businesses were contacted.

No one had seen her.

No strange car stood out.

No traveler remembered anything unusual.

She was everywhere in our minds, and nowhere in reality.

Within days, the focus started to shift.

At first, everyone said, “She must be close. She has to be.”

Then slowly, reluctantly, people started adding another sentence:

“Unless someone took her.”

Abduction.

Such a sharp, unnatural word in a small New Zealand town. It felt like a foreign language, one that should belong to big cities or movies, not to us.

But the more accidental explanations were crossed off the list—

not in the lake,

not in the house,

not in the yard,

not on the road—

the more the word “foul play” hovered in the air.

The investigation changed.

Officers looked harder at movements, timelines, cars, visitors.

They interviewed everyone again and again, including us.

Not because we were suspects, but because they were desperate for detail.

Had we seen anyone unusual that day?

Any car that didn’t belong?

Anyone walking, watching, hanging back?

No.

No.

No.

I replayed that afternoon until it almost killed me.

What if someone had stood just out of sight, timing our movements, waiting for the moment all the adults were either inside or turned away? What if the entire thing took three seconds—a hand, a scoop, a door, a silent drive away?

Three seconds.

That’s all it might take to erase a life.

As months turned to years, tips trickled in.

Sightings in other towns.

Rumors.

People swearing they’d seen a girl who looked just like her.

We chased everything.

The police followed every lead they could.

And every single time, the answer was the same:

Not her.

Someone else’s child.

Someone else’s pink jacket.

Someone else’s pain or fear or tantrum that we projected hope onto.

Do you know what it does to a person to swing repeatedly between “she might be alive” and “no, she isn’t”?

It wears down your soul like water on stone.

Decades passed.

The case officially turned “cold,” but for us, it never cooled.

It just got quieter on the outside.

Birthdays came and went.

She should have been starting school.

Then high school.

Then turning eighteen.

Then old enough to move out, travel, fall in love, live.

Instead, every year, there was just this… gap.

Like a missing tooth in the mouth of our family.

Your tongue keeps going back to it, poking it, testing it, even though you already know it’s gone.

The police reviewed the file more than once. Modern techniques. Fresh eyes. New maps. Better understanding of offender behavior, missing child patterns, rural disappearances.

In the end, their conclusion was quiet but devastating:

Given everything we know,

everything we’ve ruled out,

everything that didn’t happen—

It is most likely that my daughter was taken by someone.

“Most likely.”

Such a small phrase to hold such huge destruction.

They didn’t name a suspect.

They didn’t accuse anyone.

They didn’t give us a scene, a motive, a reason.

Just probability, built on the absence of everything else.

A reward was offered. A large one.

More calls came.

More wild stories.

More drunken “confessions” that fell apart under the simplest question:

“Okay, then where is she?”

No one could answer.

So here I am, all these years later, telling our story on the internet, to thousands of strangers who will scroll past, pause a second, feel sad, maybe comment, maybe share, and then move on with their day.

I don’t blame you if you do.

Tragedy is heavy, and everyone is already carrying something.

But if you’ve read this far, I want to ask you for two things.

First:

Hold your children a little closer tonight. Really look at them. Memorize the way their hair falls onto their forehead, the way they say your name, the way their little shoes sound on the floor. We think we have endless days to notice these things. We don’t.

Second:

If you ever hear a story, a rumor, a drunken slip, a half-forgotten memory about a child who vanished from Kingston in 1992… don’t ignore it. Don’t assume someone else already called it in. Don’t decide it’s “probably nothing.”

Sometimes the thing that breaks a case open isn’t a dramatic clue.

It’s a person who finally decides that “probably nothing” is worth saying out loud.

I don’t have a grave to visit.

I don’t have a place to lay flowers and talk to her.

All I have is this story.

And I’m going to keep telling it, again and again, until someone somewhere gets tired of keeping a secret… or until I take my questions with me when I go.

So I’ll end with this, the same question I wake up with and go to sleep with:

If you were me, would you still hope she’s alive somewhere, grown and safe but not knowing who she really is?

Or would you finally let go and accept that she’s gone, even without proof?

Be honest with me.

Because I’ve been standing between those two answers for thirty years now…

and I still don’t know which one hurts more. 💔